The head and neck of a horse. What do they have to do with balance?

The head and neck of a horse. What do they have to do with balance?

The horse’s weight is distributed between his hindquarters and forehand, and because the horse’s head and neck are very heavy, the horse carries more weight in the forehand. During movement, the horse uses its head and neck as a balance.

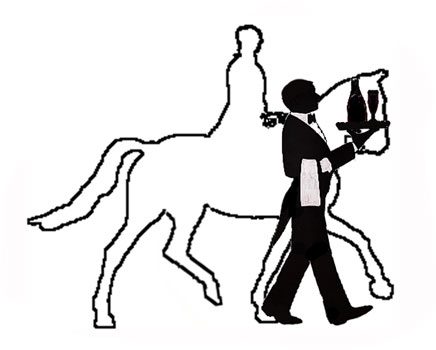

One of the key elements of dressage is to improve the horse’s balance. We train horses to take more weight on the hindquarters, thereby lightening the front, which makes the horse more agile and balanced.

Horse position in relation to balance:

In order for the horse to move gracefully and efficiently, the rider must allow him to carry himself in the best possible balance. The rider tactfully helps the horse find a position in which his hips can best take the weight of his forehand and the weight of the rider. When the horse engages (lowers the croup and takes the weight on the hindquarters), he gets enough freedom so that the nape of the neck becomes the highest point of the neck and the nose is slightly off the vertical.

The horse uses this position to help distribute the weight back.

1. Behind the vertical. Neck below. Broken neckline.

2. Slightly behind the vertical. The back of the head is at the highest point.

3. In front of the reins. The horse is far behind the vertical.

The poll should be the highest point of the horse’s skeleton. The horse’s nose should protrude slightly beyond the vertical.

The horse assumes the correct position as a result of achieving balance and relaxation. The presence of the “correct frame” can be created by force, but the position of the horse will not be natural – the animal will not be in a state of balance and relaxation.

Effortless lightness

Calmness and lightness are the hallmarks of classical work. The horse remains energetic and active, the work does not strain him, the horse is not enslaved, his muscles work efficiently. but the work does not stress her. This freedom from tension allows the muscles to work most efficiently.

The horse can certainly lighten the forehand while having his nose behind the vertical, but the imbalance that this position creates causes stiffness and tension. An unbalanced horse will not be able to perform effectively.

Because this horse is balanced, he can hold this position and even rest in this position for a short period of time.

Since this horse is not balanced, he will quickly get tired and will not be able to hold this position even for a couple of moments. There is no mention of rest at all.

Balance and relaxation complement each other. It is easiest for a horse to find balance when it is not tense. In any case, as the horse’s balance improves, his tension decreases. This is why rhythm and relaxation, the first steps of a step on the Scale of Learning, are the foundation upon which the rest of the work is built.

Johann Meixner, Richard Watchen, Kohl Handler, Nuno Oliveira and Egon von Neindorf are some of the riders who have left us wonderful examples of balanced harmony worthy of consideration and study.

Horse work behind the vertical

When the horse’s nose is behind the vertical, the force generated by his hind legs does not reach the poll. The energy reaches the part of the neck where the spine “breaks” and is extinguished under the weight of the heavy head hanging down. The load on the already overloaded front increases. Raising the gear becomes more and more difficult and the imbalance creates stress that reduces performance. Heads behind the vertical – a sign of tension. Either the horse is using the wrong neck muscles to keep his head in that position, or the rider is actively holding him behind the vertical. In any case, working with the nose behind the vertical is an unnatural way that creates imbalance and tension and goes against the basic principles of dressage.

Lifting action vs. Pushing action of the horse’s hindquarters

Pulling the horse’s head and neck down and towards you puts a lot of weight on the forehand. The horse cannot easily use its hind legs to lift the mass of the forehand. As a result, the horse puts his hindquarters back and pushes the whole mass flat.

The hind legs are set back: the corners of the joints of the hind legs of the horse are already pushed apart to the maximum. She can only use a small amount of energy to lighten the front.

If the horse’s hind legs are out, they push the horse in such a way thatоMost of the energy is directed forward and downward.

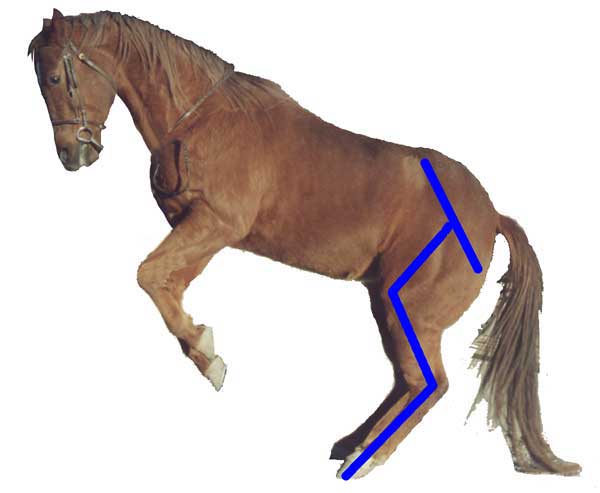

In connection: the joints of the hind legs of the horse have not yet straightened out, there is still a lot of energy saved for lifting.

When the horse has relaxed, leveled off and picked up the reins, his spine will stabilize. In fact, it can be compared to a projectile launched by her hind limbs. It moves from the back hoof of the horse, through the back, withers, neck and poll. The back of the head should be directed forward, like the front of a projectile driven from the back, through the spine, in accordance with the flow of energy.

1) The horse is ahead of the reins. 2) The horse is behind the vertical. 3) The horse is slightly behind the vertical.

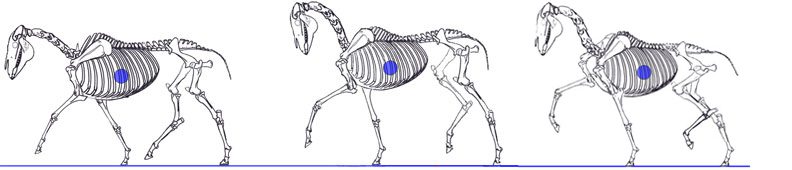

When the horse jumps she raises her center of gravity ( • ) until her hind legs can push her over the obstacle. The horse must be free to be able to raise the head and neck to facilitate shifting of the center of gravity.

Front relief

As we said earlier, the weight of the horse is distributed between its front and back. However, due to the heavy head and neck, the horse carries more of its weight in the forehand. The horse’s center of gravity is slightly above and behind its elbows (blue dot). (There is an opinion that the front legs push off the ground and lift the front up, and the body weight is shifted back. But if you watch horses properly ridden or free horses, you will understand that this is not so).

To improve the horse’s balance, we must encourage the horse to carry more of his weight on his hindquarters or, in other words, to engage his hindquarters.

Balance is maintained by controlling the body’s center of gravity over its supporting base.

Key factors that ensure the connection of the rear:

1. Flexion of the hind limbs.

When the horse is working relaxed and his back is springy, the aids can be used to stimulate pure stride impulse, which in turn causes deeper flexion of the hind leg joints.

2. Reducing the area of the supporting base.

At the beginning of horse training, we use gymnastic exercises that improve the horse’s ability to bend at the spine at the same time as bending one hind leg. These exercises involve working on one track line (circles, serpentines, and other curved lines). Later, a higher level of flexion is achieved by working on the Shoulder Forward and Shoulder In exercises. In more advanced training, exercises are used that involve bending both hind legs at the same time (stops, transitions, reins). These gymnastic exercises cause the horse to begin to bend the hind legs more deeply to move them closer to the center of gravity and reduce the supporting base. This causes the impulse from the hind legs to travel through the horse’s entire body and act on the front of the horse in an upward and forward direction. In addition, the shortening of the support base puts more weight on the horse’s hindquarters.

During the piaffe, the combined center of gravity of the horse and rider is directly above the center of the horse’s supporting base.

3. Lowering of the posterior spine.

As the strength of the horse develops, the deeper bending of the hind legs causes the spine, which is naturally lowered from the hips to the base of the neck, to begin to drop even lower in the hindquarters. In exceptionally strong and well-trained horses, the hip point (green dot) may eventually drop below the joint position between the first thoracic vertebra (back) and the last cervical vertebra (yellow dot). Since the horse’s spine is not very mobile, his hindquarters do not drop down separately from the forehand. When the rear goes lower, the front rises accordingly, and more weight is transferred to the rear. Bending the hind legs to this position requires more strength and flexibility from the horse.

4. Elastic tension of the lifting muscles.

As the horse’s muscles alternately contract and relax more deeply, the flexion of the hindquarters and the contraction of the ground base create an elastic tension (not to be confused with tightness and stiffness) in the muscles and ligaments that connect the horse’s forehand and hindquarters. This elastic tension helps lighten the front.

During the piaffe, the sensitivity of the horse’s balance can be compared to weights.

5. Natural neck lift.

The elastic tension of the muscles and ligaments contributes to the fact that the horse’s neck turns into a graceful arch, is located up and down, while the occiput becomes the highest point of the horse’s skeleton, and the head naturally goes down under the influence of gravity. The horse naturally raises his mouth to a level approximately corresponding to his hip, and his nose approaches the vertical. This natural posture allows the rein controls to transmit signals through each vertebra, through the pelvis, all the way to the joints of the horse’s hind legs. When the horse’s neck is pulled up and the nape is at its highest point, like a ballerina, the weight of the horse’s head and neck is shifted towards the hind legs, making it easier for the horse’s back to lift the forehand and transfer the weight to the hindquarters.

Hinge center.

6. Relaxation and flexion.

This is a key factor in allowing the horse’s hind legs to bend more deeply and take more weight. Connection becomes for the horse an easier task as she becomes stronger and her balance improves. Since the horse willingly relaxes into work, it naturally flexes its hindquarters as much as possible. When the horse relaxes and sits on the hindquarters, the joints of the hindquarters bend even more. This again reduces the footprint, further lowers the spine and continues to move the neck and head into a position that improves the balance of the horse.

Essentially, the horse’s spine rotates longitudinally around the horse’s center of gravity.

Train your eye to recognize the right movements

1) Free movement, open frame. 2) Artificially compressed frame. 3) Extended trot in connection.

Compare the trot of a horse in a free open working frame and in an artificially collected frame. In both cases, the horse is in the take-off phase. At first glance, an artificially collected horse seems to work higher, but if you look closely, you will see that a horse in a more open frame works and pushes off with its hind legs better. The horse’s hind legs in the free open frame still have some flexion which gives them an upward spring force during takeoff, and the horse’s hind legs in the artificially collected frame are fully extended at the knuckles – the spring is extended – the movement will no longer open. In addition, the blocked neck restricts the hind legs and the horse cannot take as wide a stride as possible.

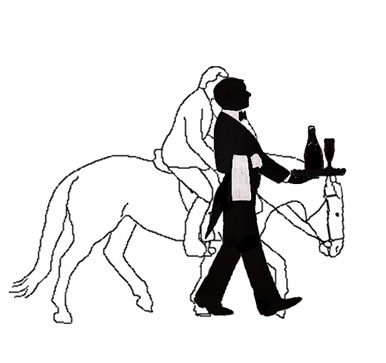

Unbalanced horse and rider in motion

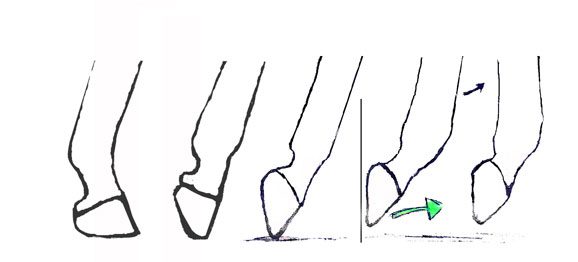

In the picture, we can see how the horse’s hind leg lands and starts to push off a fraction of a second before the front leg. Before the horse continues to move forward, stretching forward center of gravity. As the center of gravity continues to move forward, the horse’s hindquarters are no longer able to bear the weight. This horse also has to contend with the imbalance of the rider – he has destroyed his front line and absorbs the movements of the horse with his body, which, in turn, impoverishes them, hides them. If the rider is in balance and balanced, the horse will be much easier to work with.

After the back leg is bent, it begins to straighten, sending the weight of the hips forward and up. At this point, the horse’s forehand cannot use the energy from the hindquarters because the forehand is out of sync with the hindquarters. The front is compressed when the back is straightened. The position of the rider looks a little better in this frame, because in this phase of the walk the horse and goes down, but the straight position of the rider is deceptive, as he is still enslaved in the body. When the horse’s body begins to rise up, the rider will again collapse with his body down, absorbing his movements. This ricocheting movement of the rider works against the movement of the horse, further reducing the efficiency and quality of the gait.

Here the horse’s hind legs are set aside. The hind leg is fully extended, and the supporting base is so far from the limb that the horse can only push himself forward, flat, only the croup rises. Since the hindquarters are not connected, the horse moves behind the legs. On the front of the horse is now accounted for his own weight, and in addition the weight of the head, neck and weight of the rider.

As the hind legs push the horse’s weight forward, the hoof (the base of the foothold) slides back and up. Instead, the hoof should provide firm support for the horse and then move in a forward and upward direction.

The back leg is pushed forward and up. If the horse’s hindquarters straighten out before the shoulders are ready to take up the lifting motion, they will lose the lifting wave of energy created by the hind legs. They will have time to lose her even in a split second. The front legs will need to be raised in front of the horse on their own. The horse will be in the front.

Exercise “Forward and Down”

Уthe forward and down exercise helps the horse learn to move over the back, which is necessary to achieve contact. In addition, the lengthening resulting from its implementation qualitatively balances the spine, giving it effective stability in motion. Forcing the horse behind the vertical shortens and destabilizes the neck. If the neck flexes more than nature intended, hyperflexion occurs and the spine loses its stability. If you’re trying to ride forward with a misaligned spine and/or a hyperflexed neck and nape, it’s like trying to push a boiled pasta forward. The horse will not be able to move qualitatively.

If you ask the horse to carry weight on his hindquarters while his nose is behind the vertical, then you are putting too much stress on his body. This is why, almost always, when the horse is behind the vertical, his hindquarters are set back.

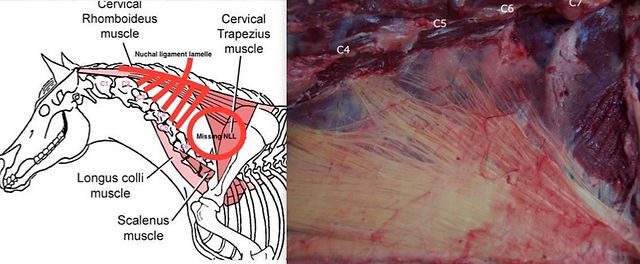

“Softening” of the neck / “softening” of the mouth

In recent years, a number of training systems have developed an exercise that aims to “soften” the neck or mouth of the horse by bending the neck into various positions. This practice, in our opinion, actually destabilizes the base of the horse’s neck, taking away his ability to use his neck to help lighten his forehand and engage his hindquarters.

By nature, the horse’s neck is flexible enough for riding. The horse can easily reach the croup with his mouth to scratch his thigh or drive away a fly. Horse stiffness and resistance are most often caused by imbalance and restlessness.

Riders must ask themselves the following questions:

- Why is my horse stiff?

- Are my own stiffness and imbalance causing my horse’s stiffness?

- Am I using the controls correctly? Is it on time?

- Is my horse working at the right pace?

- Is the contact friendly and consistent?

- Is my horse upright?

- Does my horse believe me?

- Am I asking my horse to do something that is beyond his capacity?

- Does my horse have any physical problems that are bothering him or is he in pain?

As soon as you work through each point, improve, balance, strengthen the horse, it will automatically restore its natural flexibility. There is no need to twist the horse’s neck by hand to make it more “elastic”.

As a rule, the greatest contribution to the appearance of stiffness and resistance in the horse is made by rider. It is his task to find out what causes stiffness and resistance in the horse, and effectively solve these problems. Only then can the rider help the horse regain its natural balance and freedom of movement. You can then continue to strengthen the horse with appropriate exercises that will further improve the horse’s confidence, balance and gaits. True flexibility is possible only when the horse is free from mental and physical tension and is in a state where its energy moves freely from the hind legs all the way through the spine towards the snaffle. How can you achieve this? Where to begin? From the first item on the Classical Scale of Learning…

Tonya Dawsend (source) translation by Valeria Smirnova.