Protein in the horse’s diet

Protein in the horse’s diet

After water, protein is the most abundant substance in the horse’s body, from the brain to the hooves. Protein is more than just muscle mass. These are enzymes, antibodies, DNA/RNA, hemoglobin, cell receptors, cytokines, most hormones, connective tissue. Needless to say, protein (aka protein) is a very important component of the diet.

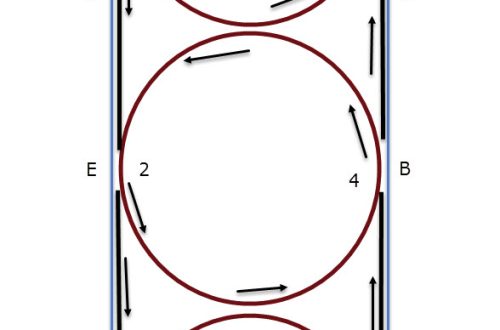

The structure of a protein molecule is so complex that it is surprising how it is digested at all. Each colored ball in the picture is a chain of amino acids. The chains are connected to each other by certain chemical bonds, which form the sequence and shape of the final molecule. Each protein has its own set of amino acids and its own unique sequence of these amino acids and the shape in which they are eventually twisted.

Protein molecules undergo primary “processing” already in the stomach – under the action of gastric juice, the molecule unwinds, and some bonds between amino acid chains are also broken (the so-called “denaturation” occurs). Further in the small intestine, the resulting chains of amino acids, under the influence of the protease enzyme coming from the pancreas, are broken down into individual amino acids, the molecules of which are already small enough to pass through the intestinal wall and enter the bloodstream. Once ingested, the amino acids are assembled back into proteins that the horse needs. ————— I’ll make a small digression: recently there are some feed manufacturers who claim that the protein in their feed is not processed in any way and therefore is not denatured and retains its biological activity, unlike competitor feeds, in which proteins are denatured and lose their biological activity in the process. thermal or other processing. Such statements are nothing more than a marketing ploy! First, getting into the gastrointestinal tract, any protein is immediately denatured, otherwise a huge protein molecule simply cannot be absorbed into the blood through the intestinal walls. If the protein is already denatured, it’s just faster digested, because you can skip the first step. As for biological activity, it refers to the functions that a specific protein performs in the body. With regard to the horse, the biological activity of plant proteins (for example, photosynthesis) is not very necessary for her. The body itself assembles proteins from individual amino acids with the biological activity necessary for this particular organism.

—————- Proteins that do not have time to be digested in the small intestine enter the posterior intestine, and there, although they can nourish the local microflora, they are already quite useless for the horse’s body (from there they can only proceed to the exit). Diarrhea can be a side effect.

The body constantly breaks down existing proteins and synthesizes new ones. In the process, some amino acids are produced from others that exist, some that are currently unnecessary are removed from the body, because the ability to store protein for the future does not exist in a horse (and any other, probably) organism.

Moreover, the amino acid is not completely excreted. The amino group containing nitrogen is separated from it – it is excreted, having gone through a complex path of transformations, in the form of urea with urine. The remaining carboxyl group is stored and can be used to generate energy, although this method of obtaining energy is rather complicated and energy-consuming.

The same thing happens with extra amino acids that come from food with protein. If they managed to be digested and absorbed into the blood, but the body does not currently need them, nitrogen is separated and excreted in the urine, and the remaining carbon part goes into reserves, usually fat. The stall smells stronger of ammonia, and the horse increases its water intake (the urine must be made from something!)

The foregoing brings us to the question of not only the quantity, but also the quality of the protein. The ideal quality of protein is one where all amino acids are in exactly the same ratio in which the body needs them.

There are two problems here. First: it is not yet known exactly what this amount is, the more it will change depending on the state of the organism. Therefore, at the moment, the ratio of amino acids in horse muscles (and in lactating mares – also in milk) is taken as an ideal, since muscles are still the bulk of the protein. To date, the total need for lysine has been more or less accurately investigated, so it is normalized. In addition, lysine is considered the main limiting amino acid. This means that very often foods contain less lysine than needed compared to the rest of the amino acids. That is, even if the total amount of protein is normal, the body will be able to use it only as long as it has enough lysine. Once the lysine runs out, the remaining amino acids cannot be used and go to waste.

Threonine and methionine are also considered limiting. That is why this trinity can often be seen in dressings.

By quantity, either crude protein or digestible protein is normalized. However, it is crude protein that is most often indicated in feeds (it is easier to calculate), so it is easier to build on the norms for crude protein. The fact is that crude protein is calculated by the nitrogen content. It’s very simple – they counted all the nitrogen, then multiplied by a certain coefficient and got crude protein. However, this formula does not take into account the presence of non-protein forms of nitrogen, so it is not entirely accurate.

Nevertheless, when setting standards for crude protein, its digestibility is taken into account (it is believed that this is about 50%), so you can fully use these standards, remembering, however, about the quality of the protein!

If you pay attention to the nutrient content of feed (e.g. on the label on a bag of muesli), then keep in mind that it happens both ways, and you should not compare the incomparable.

A lot of controversy is caused by an excess of protein in the diet. Until recently, it was widely believed that “protein poisoning” causes laminitis. It has now been proven that this is a myth, and protein has absolutely nothing to do with laminitis. Nevertheless, protein opponents do not give up and argue that excess protein negatively affects the kidneys (because they are forced to excrete excess nitrogen) and the liver (because it converts toxic ammonia into non-toxic urea).

However, veterinarians and dietitians who study protein metabolism claim that this is a myth, and that there are no reliable cases of kidney problems in the veterinary history due to excess protein in the diet. Another thing is if the kidneys are already problematic. Then the protein in the diet must be strictly rationed so as not to overload them.

I will not argue that a strong excess of protein is completely harmless. For example, there are studies showing that an increased amount of protein in the diet leads to an increase in blood acidity during exercise. And although the study does not say anything about the consequences of increased blood acidity, in principle this is not very good.

There is also such a thing as “protein bumps”. However, most often these rashes have nothing to do with the diet. Very rarely, an allergic reaction to a particular protein can occur, but this will be a purely individual problem.

And in conclusion, I want to say about blood tests. In blood biochemistry there is such a thing as “Total protein”. While a total protein reading below the target can (though not necessarily) be indicative of insufficient dietary protein intake, a total protein above the norm has nothing to do with the amount of protein in the diet! The most common reason for excess total protein is dehydration! The excess of the actual protein in the diet can be indirectly judged by the amount of urea in the blood, having previously excluded, again, dehydration and kidney problems!

Ekaterina Lomeiko (Sara).

Questions and comments regarding this article can be left in блоге the author.