Negative Reinforcement in Horse Training: Pros and Cons

Negative Reinforcement in Horse Training: Pros and Cons

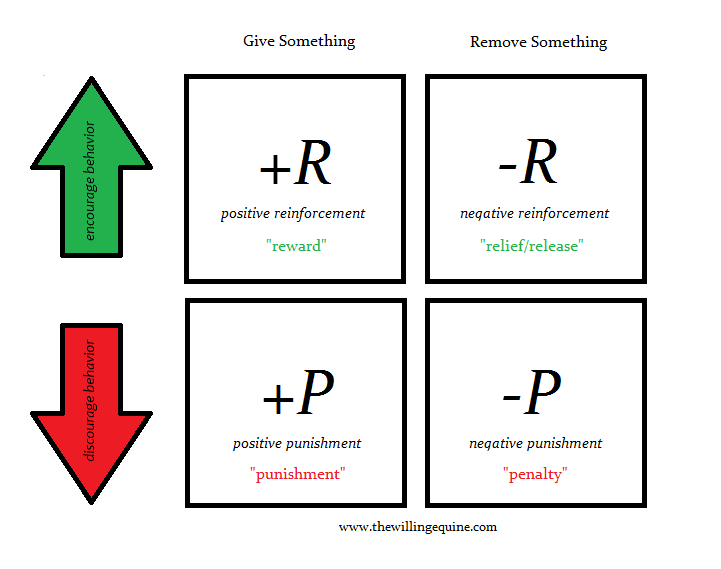

The phrase “negative reinforcement” is often misunderstood. Yes, many people know this term, but hesitate to give it a clear definition.

So let’s start at the beginning: negative reinforcement is a learning tool where painless pressure is applied until the horse responds in the desired way. When the horse responds, the pressure is released. Over time, the horse associates this particular response with the appropriate response.

A simple example of negative reinforcement is the unpleasant beep that occurs when you don’t fasten your seat belt in a car. He will annoy us until we buckle up. If you are riding, negative reinforcement is used when you press your legs against your horse’s sides and then release that pressure when he starts to trot. Through association, the horse learns that equal leg pressure on both sides of its body means “trot.”

The horse’s brain is wired to look for associations, whether they are consciously provided or not. Because horses are always looking to make these connections, we need to give them an idea of what is expected and what is forbidden. If the person doesn’t make those decisions, the horse will make it for him, but his ideas of right and wrong may not match ours.

Negative reinforcement is the most common form of associative learning used in horse training. This is our natural “mode” by default, we “turn on” it with particular ease. But let’s take a closer look at its strengths and weaknesses.

Negative reinforcement in practice

Negative reinforcement works best when it is applied in a form that matches the nature of the horse. Researchers Andrew McLean and Jane Christensen note that horses use “moving” as a negative reinforcer among themselves. The dominant mare only needs to turn one ear to force the inferior mare to move away from the food. The horse displaces you by flailing its head, stepping on you, pushing or kicking – it knows how to move you if you let it. Because horses use natural movement, we can use this feature for training purposes.

When you ride, you use a type of pressure that takes into account the horse’s tendency to move. Take, for example, leg pressure. Why don’t we tighten the biceps or words like “faster” to speed up the horse? Leg pressure mimics the natural means that “move” a horse—the horse moves away from pressure applied to its flanks, no matter who is applying it. If you push on the left side of the horse, it will move to the right and vice versa. Equal pressure from both sides will cause forward movement – the horse will tend to avoid the pressure. Theoretically, a horse could choose to move backwards (even on a free rein), but reverse movement is not so natural for him and, therefore, such manifestations in mature horses are quite rare.

As soon as the horse responds in the way the rider wants (for example, moving from a walk to a trot), he releases the pressure and the horse perceives it positively. Horses don’t like pressure and will work to avoid it. If you release the pressure immediately, the horse’s brain will associate the action with the result. The next time you hit his sides with both legs, the horse will speed up again, hoping to achieve the same result.

“Balls and rollers”: how the horse’s brain works

Physiologically, the link between pressure and pressure release occurs when two neural networks become connected by simultaneous activation. One group of neurons in the horse’s brain is responsible for the sensation of pressure. You press, she feels, and certain brain cells “light up.” Another set of neurons is responsible for forward movement. When two networks fire at the same time or side by side, they are linked by a process we call “long-term potentiation.”

Long-term potentiation is a form of memory. Activated neurons remain more awake for a few seconds after the initial “arousal”. In this short period of time, they run faster and more intensely. The release of pressure at this point causes the two networks to connect. Too early – and the first network has not yet been activated. Too late and the memorization didn’t work. Proper timing is essential to create a connection between your pressure and the horse’s response.

Trainers use negative reinforcement to train young and/or inexperienced horses to respond to any kind of human-initiated pressure. The first gallop under the saddle of a young horse is usually embarrassing. She moved at a walk and a trot, learning the basics of stopping, moving, turning, and so on. But getting into a canter under the rider is something new… Suddenly the trainer is using only one leg pressure, but the position of his body and a slight cue of the rein tell the horse to accelerate. If a horse thought like a human, it might wonder, “Hmm, this is different from a normal trot. What does this mean?

With the constant pressure of one leg and some discomfort from moving at a fast trot, the young horse will eventually try to get up into a canter. Imagine her saying, “OK, it’s not a fast trot because his foot is still only pressing on one side of me. I can try to raise my head; no, not that again. How about a stop? No, he pushes with both feet when I do it. Well, let’s try a little canter…” The moment the horse starts to canter, the trainer releases leg pressure and begins to follow the horse. Now the horse knows: “Aha! That’s what one leg means.” Her brain uses long-term potentiation to connect the two networks and learn the lesson. Over time, we will begin to sharpen the horse’s perception of our signals in many different ways.

More difficult learning stages and negative reinforcement

Negative reinforcement works best in the early stages of horse training, but it is also used in more difficult stages. An example would be a half halt and a descending transition. Let’s say you want to bring your horse from a trot to a walk. You use your seat to slow the horse down by resisting forward movement with your seat. She feels this pressure and responds to the request by slowing down to match your rhythm. As she transitions into a walk, you release the pressure from your seat and move with her again. This is how the horse learns the half halt and he will respond more readily each time as his neural networks continue to fire simultaneously through multiple repetitions.

The seat of the rider is the most important source of pressure. A competent rider can apply seat pressure in many variations – with different strengths and in different directions – up, down, left, right, forward, backward, diagonally and in a circle. After all, a highly skilled horse will respond to changes in seat position and force very precisely and subtly. In this case, an experienced rider will be able to place any part of the horse’s body in any possible position with only his seat at a walk, trot or canter.

Work is another form of pressure on the horse, and rest is a release from it. Let’s suppose that a horse sometimes goes under the saddle. If you have the skills to handle the situation, don’t stop or slow down when the goats start – just make the horse work. As soon as she starts to goof off, send her into an active fast trot and move her for a minute. When the horse goes forward easily without the goats, pat him on the neck and let him walk on a long rein. Then repeat the original maneuver. Every time the horse starts to goof off, push him forward, forcing him to do more difficult work. We are not trying to tire the horse in this way. We show her that she will be relieved of the pressure of work as soon as she stops being a jerk.

Disadvantages of Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement is useful for horses who are simply learning to carry a rider and interpret his signals. It is also useful for horses in need of correction of certain behavioral deficiencies. Many horses are trained exclusively with negative reinforcement, and it gives excellent results.

But negative reinforcement can also create problems.

At first, it must be used at a particular moment. Many recreational riders have trouble coordinating their movements with the movements of the horse. Think back to your first canter, the trot, when you were like a sack of potatoes. “Hold your left leg behind the girth!” Many of us thought at such moments not about the leg, but about not falling, and not about the timeliness of action.

Second, the coordination becomes even more challenging when we need to both apply and release pressure at the same time. Since long-term potentiation is very short-lived, your actions must follow each other in time, in time to respond to the horse’s responses. Imagine that you are training a horse to leg yield, where it should be straight from head to tail but moving diagonally with leg pressure. To teach this skill, the rider applies pressure with the outside leg during the hind leg phase of the horse. The “moving phase” is that micro-moment when the horse has already lifted its leg off the ground, but has not yet lowered it. So you apply outside pressure behind the girth when the drive phase begins, and if the horse responds by moving the outside hind leg diagonally, you release the pressure before the drive phase ends. This interval at medium trot lasts less than half a second!

The third the problem can be created by accidental unintentional reinforcement. You are cantering and you need to use your left rein a little to start a big circle. But you “trigger” too much, the horse turns around sharply (according to your request), and now you are already sitting on the ground. By falling, you relieved the horse of pressure and taught him a beautiful, clear lesson. If a horse could talk, it could say, “Wow! She herself wanted me to turn sharply. I did this and she instantly took all the pressure off. I will do the same next time!”

Good riding skills discourage inadvertent reinforcement. Sitting in the saddle, with the weight down on the heels, straightening the body, not stiffening the arms, moving the seat and legs with the horse, we can give him clear signals, consistently repeating them over and over again.

Fourthly, riders sometimes mistakenly confuse “pressure” and “punishment”. The pressure of negative reinforcement may be irritating or shifting at first, but it should never be painful or traumatic! Punishment, as an educational tool, can cause serious problems and should only be used by highly qualified trainers in rare cases of egregious horse behavior. Punishment is the least effective means of learning!

Perhaps most importantly, negative reinforcement teaches the horse to obey and respond, but it does not create trust or attachment between horse and rider. It encourages the horse to seek out, identify and use the rider’s signals, but it doesn’t provide the bonus of building a trusting relationship with the horse.

pressure release skill

Releasing pressure is the most important component of negative reinforcement. Technique will be misused when the rider applies pressure but fails to release when the horse responds. This error is unfortunately quite common. Horses will not respond well and properly when given permanent pressure. Some lose all motivation, while others become too nervous. The horse can start to goat, shine, upset, beat off. In this case, the principle of “fix and remove” can help.

The influence “fix and remove” is used in all areas of communication and interaction with the horse, starting from leading it on the lead next to you. Constant corrective pressure (for example, when the horse lies down on the rein) interferes with learning, irritates or frightens the horse, and forces you and the horse to compete in tug of war. No matter how strong you are, you will never outweigh a 500 kg horse. Instead, she will become tight-lipped, star-gazing, and unwilling to cooperate with you (you will, however, get great biceps).

To avoid constant pressure, try using a series of presses, releasing the series when the horse responds correctly. (Remember the seatbelt signal? The signal doesn’t need to be continuous to get us to buckle up, the pressure is repeated short beeps.) Add other ways to slow down to help your horse decipher your signals: weight your seat by bending your elbows, softening your legs, easing slower by taking more vertical position.

Negative reinforcement is the most common form of associative training for horses, but it requires superior coordination, timing, and riding skills to use. It teaches the horse to respond the way a good soldier does, but it rarely motivates the horse to cooperate and trust the rider.

Janet L. Jones (source); translation Valeria Smirnova.