Lateral movements from the horse’s point of view

Contents

Lateral movements from the horse’s point of view

Straight ahead

One of the most important things you need to understand before you start working on lateral movement is that lateral movement is not natural for a horse and cannot be performed for long periods of time. The horse is designed to move forward.

Forward movement.

This doesn’t mean it can’t move sideways or turn, it just means that the horse’s natural way of moving is to move in straight lines. But why?

Because the joints of the forelimbs of the horse are mobile in the direction along the body. The same applies to the hind limbs from the hock and below. Try to check this next time you take the horse’s leg to unhook the hoof.

Joints can be compared to door hinges that only work in one direction. The surface of the joint allows smooth sliding in one direction, and extremely strong ligaments and tendons prevent lateral movement of the joints, even accidental.

However, horses can still move sideways. How is this possible?

The forelimbs of the horse can move sideways. This movement is made possible by the scapula and its articulation with the horse’s body. Remember, there are no joints here, only muscles and ligaments that can allow the leg to deviate from a straight line.

The muscles that perform this task are actually designed for something else. Therefore, we need to ensure that lateral movements are performed without injury and damage to the health of the horse.

The hind legs are able to move sideways a little more freely, thanks to the design of the hip joints, mobile in all directions. However, it must be taken into account that the range of their movement forward / backward is much greater than the range of movement to the side. This is due not only to the structure of the joint, but also to muscle mass, and muscle attachment sites, and applied force/resistance to the bone.

Since the horse always puts her hind legs parallel to the body and does not take them to the side, respectively, and her muscles do not become more elastic for stretching in a side direction. Horses that are trained to be flexible and supple by professional trainers have much greater lateral mobility in the hindquarters than untrained horses.

In order for the horse to be able to leave the leg away from the straight line (cross the midline of the body) and keep the weight of the body on this leg or set it off the body, proper training is needed, which will make the horse’s muscles stronger and more elastic.

When working on lateral movements, the rider must be very careful not to require the horse to take many steps to the side in one set, so as not to injure him. It is important to be patient and prepare the horse for this unusual task.

Shoulder in

Shoulder-in is a complex lateral movement, the purpose of which is the complete training of the horse. First, I will try to explain how it is done. When moving along the long wall of the arena, riding to the right in front of the horse moving away from the wall, the body bends as if you are about to perform a small circle.

Shoulder inward to the right.

The degree of deviation from the straight position depends on your goals and how well the horse can bend without losing momentum and rhythm. This may be the distance at which the outer forefoot steps in a line between the hind feet. The horse’s inside hoof follows the line of movement of the inside hind foot. This movement is sometimes called shoulder forward (from him.Shoulder-before).

Shoulder forward. Front outer legand the lines between the two back.

From the representatives of the German school of riding, who are usually so convinced of their own rightness that they consider all opinions different from their own to be wrong, it can be heard that the inner hind hoof should run exactly in the same line as the outer front. In this case, the outer hind and inner front hooves go their own way. I have depicted the same here, but not because I think this method is the only correct one (it is not), but because this is a good average shoulder inward and it is best to start with it if the horse has already been taught to yield before this.

You can also shoulder inward with this bend, when in front of the horse moves on the second track, and the rear does not follow the footprints of the front at all. This requires a high level of flexibility from the horse. The horse must havethe ability, without loss of rhythm and momentum, to bend in the body in such a way that the forehand moves along the second line of the trail, and the hindquarters move in a straight line forward. Or the horse’s hindquarters do not move in a straight line, but are slightly at an angle and the hind legs, like when yielding to the leg, cross.

Shoulder in. The front and back move along two different lines of motion.

This execution of the shoulder inward may seem controversial. Is it right or not? But the fact remains that the author of this movement (De La Gueriniere) clearly described the presence of a cross movement of the hind legs when performing the shoulder inward. Perhaps the execution technique was adapted later. The shoulder with a straight movement of the buttocks is accepted in the German school.

Shoulder in. Fulfillment adopted in the German school.

When we say “shoulder in”, we don’t automatically mean “inside”. The horse can shoulder-in to the right, bending to the right, and the arena wall can be on the right side of it. The classic execution that we are used to makes it easier to start learning how to perform this element. You can move the horse’s hindquarters in a straight line and shift his front from the wall to the center. It will be easier for you to appreciate how far the horse’s shoulders are turned inward relative to the line of motion.

In addition to maintaining rhythm, momentum and contact, you should also pay attention to one important thing is the bending of the horse in the body. Very often the horse only bends at the neck, and the shoulder falls out. This happens when the rider cannot bend the horse at the side and tries to get the horse in the correct position with the reins. This is a wrong execution.

False bend. Incorrect execution of the shoulder inward.

Many people say that the horse should evenly bend in the body from the back of the head to the reptile. But this is impossible. horse physically can’t do that! She needs to make a decision inside (lose her jaw and bend at the second cervical vertebra so as to look inward). She then flexes her neck and chest evenly in a smooth arc. The fold line should be uniform.

How the horse bends.

The area behind the saddle cannot flex. The spine is not flexible. In order to compensate for the lack of flexion, the horse must lower the inside thigh a little and flex the leg at the knuckles (it actually moves slightly forward). This is part of the collection of the shoulder-in element required to maintain contact. If this condition is not met, the shoulder inward turns into leg yield.

Let’s not forget about the tail. The tail is the last section of the horse’s spine. Tail curl is an indicator that the horse is relaxed and bent over the entire back, not tense or blocked. Pay attention to him. Thus, one of the goals of doing the shoulder inward is lowering the inner thigh and flexing the joints of the inner leg. Stretching the horse on the outside (and not just bending on the inside) is also important. This will strengthen the topline muscles and improve contact with the horse’s mouth. Stretching the outside of the horse, combined with contact with the hand, will help to further regulate collection and pace.

Shoulder in. Correct execution. The horse takes steps towards the center of gravity.

When shouldering in, the horse moves from the hindquarters, which supports the forehand, making it easier. In the photo above, the right hind leg is directly behind the horse’s center of gravity. The outside leg is slightly relieved of weight, as is the inside front leg. The inside hind leg must not only push the horse forward, but also carry the load, which even increases as the rider shifts the weight to the inside.

Doing a shoulder-in exercise will encourage the horse to put his weight on the inside hind leg. As soon as the horse lowers his inside hind leg to the ground and lifts his outside one, he is in action. But they don’t work only the hind legs of the horse. The front legs are also involved and bear the load. The chest muscles must be stretched to provide the desired flexion. They also support the front in such an unnatural position for the horse.

thigh inside

Flexing the inside and stretching the outside.

The hip inward is otherwise called a traverse. However, there is a nuance. The traverse is performed diagonally or quarter-diagonally so that the horse’s hips are somehow on the long side of the arena. If the shoulders are on the long side (and the hips are outside), then ranvers takes place. It all depends on where the horse is in the arena. But the hip-in is the hip-in, you can do it even in the field, without fences.

The goals of the hip-in exercise are the same as those of the shoulder-in exercise. It must gather the horse and balance it on the hindquarters. The hip inward is performed a little differently than the shoulder inward: The horse’s shoulders are moving straight forward (or almost so) and his hips are at an angle. The outside hind leg is placed behind the center of gravity and steps under it during movement.

In order to successfully execute the hip-in, you need to train the horse to some degree of collection and practice the shoulder-in with him. The horse must not walk with the shoulder out. This mistake when doing the hip inward will not be corrected.

The horse must also be able to flex as it moves forward. Now the forward movement is provided by the outside leg, which carries a large load.

Properly executed thigh inside.

It is important that the hip-in can also be performed at a canter, and such work will have a better effect on the collection of the horse than work at a trot.

Shoulder-in cantering, however, is a very difficult and potentially dangerous task. The reason for this is the intersection of the front legs. When the outer front touches the ground, the inner front must land on the ground in front of it. The horse may become entangled in the legs or hit itself. When performing hips inward at a canter, the hind legs cross. The crossing takes place in the air and does not create problems. The problem may be that the hind leg of the horse, which will carry all the load when landing, may become on the second line of the track, and not under the body, closer to the center of gravity.

leg yield

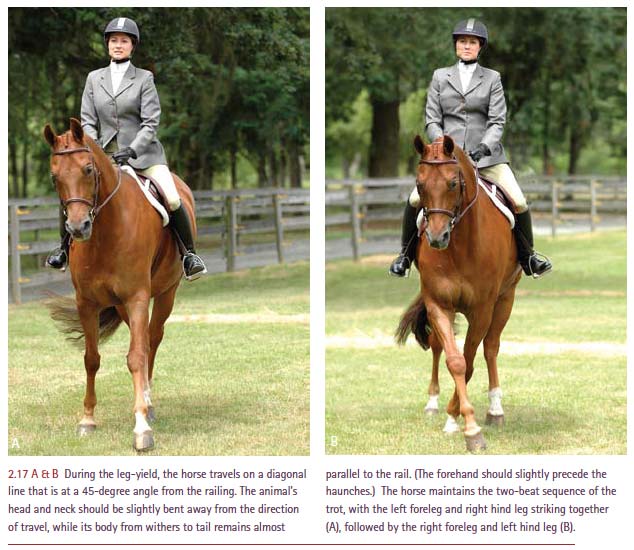

Leg yield to the left. Front and hind legs intersect.

The leg yield is the “little brother” of shoulder-in and hip-in. In the French school of riding, concession as a separate element is not considered at all, while the Germans use it less and less often in their dressage tests.

The leg yield as an exercise basically has three goals: 1. It teaches the rider to use the diagonal aids of the inside leg and outside rein. Until the rider coordinates these two messages, there can be no question of any successful fulfillment of the concession. 2. It teaches the horse to move with the pressure of the leg, which gives the rider control over the horse’s hindquarters. This elementary and very important skill is necessary for the successful development of a young horse. 3. It can be used as a great exercise to warm up the horse. The angle of movement of the legs does not match the direction of movement of the horse. By yielding in both directions, you activate many dormant muscles and joints. Leg yielding has no gathering effect on the horse. The horse is moving at too steep an angle so that the hind legs do not have time to move under the horse’s center of gravity. The hindquarters do not carry additional loads. However, it should still be used with caution, as it can lower the horse down.

Front turn

Turn left ahead.

Pivoting on the forehand does what leg yielding does – teaches the horse to move away from the leg. However, the difficulty for a horse, especially a young one, is that it practically does not move forward. If the horse is young or unprepared, it is best not to turn 180 degrees and increase the number of steps gradually.

A step or two, moving 1,5 meters to the inside, so that the horse turns at least approximately a small angle, can help bring the inside hind leg in without losing momentum.

Many riders cannot always tell which turn they are making. If the front legs are conditionally in one place, and the hind legs move, then what kind of turn is this? On the front or on the back?

It is easier to determine by paying attention to the balance of the horse. So:

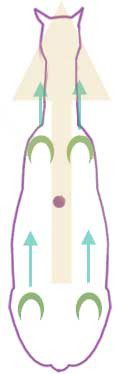

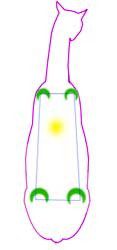

The center of gravity is stable at one point. The horse stands still.

The horse stands, maintaining balance, evenly on 4 legs. The center of gravity (yellow dot) is located approximately under the central part of the horse, closer to the forehand. If the horse were a stone statue, it would be able to stand using only one support, which was located would at this point. But the horse has four legs (green dots) arranged like pillars at the four corners of the rectangle. The center of gravity is approximately in the center, closer to the front hooves. This is due to the fact that the neck and head of the horse outweigh the front.

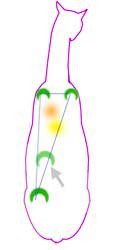

The center of gravity shifts forward as the back foot leaves the ground.

When a horse lifts its hind leg to move it, the center of gravity shifts away from that leg. Otherwise, this side will fall, since it is outside the triangle formed by the three pillars. The heavy body is still in place, but one support has disappeared – the point of balance must shift.

Therefore, when the horse makes a turn on the forehand, for example, to the right, then the center of gravity shifts to the left. The horse lifts his right hindquarters to place it in front of his left hindquarters. The horse must shift the center of gravity so that it is constantly within the triangle. To prevent the rear leg from taking on double the weight, the center of gravity shifts to the front.

The front legs do not take wide steps. They mostly step over in place, the left front steps over a couple of inches, so there is no deviation from their direct support function. The hind legs, on the contrary, move to the side and take wide steps, so they should be as light as possible. The center of balance is always in front. You can say that this is not productive and contrary to what we are moving towards. We are trying to shift the horse’s weight into hind balance. But the fact remains, the turn on the front is made on the front balance. Once the horse begins to work in collection, you will no longer need to turn on the forehand.

What the forehand pivot does to improve collection is to exercise the joints of the horse’s hind legs, making them more flexible and agile.

A common disadvantage of forehand turns is that the horse does not lift its front (or front) legs, but simply rolls over. Then, when it is physically impossible to roll any further, the horse takes a forward step that is out of sync with the hindquarters.

The most extreme situation occurs when the horse is so front-heavy that he does not lift his front legs at all. It scrolls on the front, screwing into the ground. The solution to this problem is to turn on the front so that the front legs also move in a small circle.

Rear turn

Turning on the back is a completely different matter. It is also called the walk pirouette. It is not as hard a pirouette to perform as a canter pirouette, but it does not cease to be a pirouette. The horse puts more weight on the hind legs to take the load off the front legs and allow them to step over.

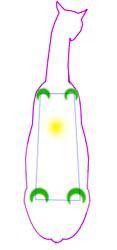

The horse stands still, the center of gravity is motionless.

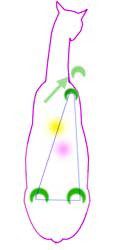

The horse stands in balance, its body is supported on four supports located at the corners of the quadrangle. The center of gravity (yellow) is located approximately in the center, closer to the front of the horse. The horse lifts the right front off the ground and shifts it to the right, the center of gravity shifts to the hind legs, also to the right (pink dot).

The center of gravity shifts away from the raised front leg.

When the horse makes a forehand turn, the hind legs make a circle around the horse’s forehand. The hind legs cross each other during movement. When turning on its hindquarters, the horse makes a circle with its front legs around its hind legs. front legs step in front of each other, away from the back. Therefore, if the messages of the rider are inconsistent, it is very easy for the horse to stretch out, move from its place and go forward.

Perhaps it would be better for us to ask the horse to cross the forelegs behind each other on the hind turn in order to force the forelegs to step closer to the hind legs?

On the plus side for us, the outside hind leg should also step around the inside hind leg. In this way, she steps ahead of the inside hind hoof, which forces the hind legs to follow the receding forefoot.

Teresa Sandin; translation by Valeria Smirnova (source).