Work on the development of the musculature of the horse

Work on the development of the musculature of the horse

The purpose of changing the horse’s postural reflexes is to help him better move. However, it is often forgotten from the very first minutes of training. Why? Different muscles of the horse’s body serve different purposes, but unfortunately riders often fail to activate the muscles that need to be activated at any given moment. However, activating the wrong muscles can cause other problems, such as stiffness or limited joint flexion, which is counterproductive for dressage purposes.

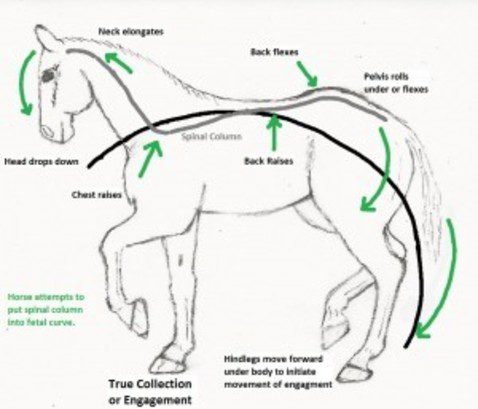

During training, many riders activate the horse’s “gymnastics” muscles (large external muscles that serve to move). They are responsible for moving the horse from one place to another, but are not effective in communicating with the horse’s nervous system in terms of recruiting new muscle structures or reinforcing muscle memory. Excessive gymnastics of the horse can quickly lead to stiffness, and if this happens, the horse’s reflex system will change, preventing adequate joint flexion. So, for example, a horse can have very strong back muscles, but they do not allow it to move freely. According to veterinarian Dr. Gerd Heuschmann, the tension resulting from excessive back muscle tone actually slows down the horse’s hind legs and creates a leaning habit rather than improving agility and balance. Similarly, the gluteal muscles, when disproportionately strong relative to adjacent smaller muscles, can restrict the free movement of the hind legs. According to Heuschmann, many modern riders misunderstand the concept of power. They spend too much time trying to get the bright wide gaits they think dressage needs. But the concomitant endless repetition creates bondage and asymmetry.

“You have to make your horse an athlete. A horse that is only worked on developing gaits becomes boring,” he says, referring to horses that have been trained to strengthen their topline and hindquarters, or have been working on “wide” gaits daily while developing their postural muscles, such as the multifidus muscles or the stabilizing muscles of the spine or pelvis, were neglected.

When the rider needs to change the horse’s muscle structures or muscle memory, he must focus on stimulating the smaller muscles deep in the body, near the spine and around the joints, often referred to as the intrinsic muscles. Think of them as the guardians of your horse’s language of movement. By activating these muscles in addition to the larger muscles, new neural pathways are established and/or existing ones become more refined.

Heuschmann says that for most riders this can be achieved by riding at slower speeds. He refers to the slow warm-up jog that Alois Podhajski of the Spanish Riding School especially appreciated. This slow gait allows the horse to move easily by flexing his joints and working his back before we add more momentum. Podhaisky also noted the benefits of one of the most beneficial rehabilitation protocols used by the cavalry. It involved riding a long rein down the slopes until the horse dropped his neck and relaxed, allowing his nervous system to reorganize. Sometimes this required months of work, but nothing changed until the appropriate effect was achieved. “Any horse that is tense at the poll or back will lose their natural rhythm,” Heuschmann said.

According to Sarah Le Juin, MD, DVM, Equine Integrative Sports Medicine Center, UC Davis, in general, motor muscles are easier to train than postural muscles, which requires a number of specific exercises. However, this aspect of training requires further research, le Juin acknowledges, since much of the evidence available on the applicability of physical therapy to horses comes from human studies and is therefore not always applicable to quadrupeds.

“We know that pain inhibits normal muscle activation and can actually lead to deactivation of normal muscle pathways,” Le Juen says. Pain can be the result of injury, overexertion, or an imbalance in muscle development. The most effective daily strategy for changing the horse’s muscle structures seems to be to first get rid of that pain or stiffness through physical methods such as trigger point work, joint movement work, and dynamic stretching. Only then can we begin to perform corrective exercises, and then move on to regular training.

The exercises below are useful for the first 10 minutes of the warm-up phase before starting regular work. Try doing them for six weeks, noticing any changes. You will most likely see progress. Experiment with different exercises, as some will give you better results than others. Find the ones that make measurable changes.

Exercises 1 and 2: Reducing Tension to Improve Range of Motion

From the point of view of Jim Masterson, whose method was used by the US team, of paramount importance for improving the athletic form of the horse is moving the joints of the horse and its limbs through the full range of motion without resistance or tension. According to Masterson, it is best to perform the appropriate exercises daily, when the horse’s motor muscles are not yet engaged. When moving in a completely relaxed state, three things happen: 1) the horse senses where the tension is; 2) she releases this tension and 3) her nervous system is reprogrammed. “The key is not the amount of movement, but the amount of relaxation in movement. Asking for even a tiny range of motion in a relaxed state is 10 times more effective than asking for a “big” but tight movement, Masterson explained.

Exercise 1 It is aimed at relieving tension in the vertebrae of the back of the head, atlas and neck.

Stand at the horse’s head and place the fingers of your outside hand on the horse’s nose. Gently place two fingers of your other hand on your neck, about a palm’s width below and behind your ears. Soften your arms and hands so that you barely touch the hairs. With your left hand, gently (about a centimeter) move the horse by the nose from side to side. Do four swings and stop. This is to check if the movement is relaxed. Rock again and then stop. Repeat this several times. If the horse finds this uncomfortable, he will feel tension in the postural muscles of the spine in that area. Don’t try to stop her from wagging her head. Instead, soften your arms even more and wiggle them in even smaller movements. This will give the horse the opportunity to relieve tension in greater comfort. Make the range wider every day. “The reason the wiggle works is because it’s a small movement in a relaxed state that the horse can’t fight,” says Masterson.

Exercise 2 It is aimed at relieving tension in the entire spine, from the sacrum to the back of the head.

Stand behind the horse, at his hip. Gently lower your right hand to the sacrum, placing the brush over the base of the tail. Relax your arms and hands. Using the base of your right hand, gently rock the horse’s hindquarters a centimeter or two, observing the rhythm of the swing as far as the nose. The horse’s head should swing from side to side. Continue for at least two minutes.

Exercise 3: Using Sensory Relearn Tracks

Once you have released the blocked areas of the horse’s body, you can introduce new muscle patterns by using the following corrective exercises during the slower part of your warm-up. The use of sensory relearning tracks has become popular in rehabilitation facilities because they increase the horse’s proprioception (his awareness of his own body position in space), which in turn helps the horse move more smoothly and know where his feet are.

We use three meter alternating surface segments that the horse walks over a total of 30 meters or more. These segments may include pebbles, hard earth, water, sand, and grass. Therapists use these tracks to wake up the horse’s neuroreceptors that provide mobility to unused areas of the neuromuscular system. This is especially true for horses that train mainly on a special ground of the arena. Tracks help the horse improve limb reaction time, joint flexion, and postural muscle engagement.

If you are unable to build sensory paths, you can take the horse outside the arena and look for different surfaces there: gravel, wood chips, pavement, grass. Try to walk or trot slowly on these surfaces three times a week for 5-10 minutes. Try not to tell your horse – let him figure out how to walk on different types of surfaces.

Exercise 4: Adding a ditch or drop

Usually we ride on triathlon grounds where there is a ditch, the horse goes down a steep descent, takes a couple of steps, and then immediately rises to the other side, which requires coordination between front and hind legs and quick balance adjustments. These adjustments help the horse lift the base of the neck and stabilize the pelvis. They also help correct asymmetries, as the horse must bend and push off with both hind legs equally. If the horse gets used to moving in the arena slightly twisted, the ditch enhances the effect of the twist, allowing the rider to see it and correct it gradually and in a controlled manner.

If you have access to a ditch, walk through it at a controlled pace, keeping your horse level so that his butt doesn’t “walk” from side to side. Do this exercise five to eight times a day. If there is no ditch, you can improvise. Those, for example, if there is a stream with steep banks nearby, you can practice there. Another option is to build a raised catwalk, a platform that the horse will climb onto and then descend from.

Exercise 5: side steps

Lateral movements increase the mobility of the intervertebral and hip joints, while at the same time engaging the small muscles that stabilize them. Thus, a simple front turn, when performed correctly, mobilizes the chest and releases the restriction in the horse’s ventral muscle chain, which connects the horse’s pubic bone and abdomen to the jaw and tongue. Therapists sometimes refer to this as Horse Pilates. On horseback or in the arms, perform three full rotations (360 degrees) daily in front in both directions. The horse’s hind legs must cross over with each step. forming an X. Check that the horse crosses the legs equally when turning to the right and when turning to the left.

Exercise 6: Earth

Poles on the ground are often included in rehabilitation or neurological programs because they play a role in both changing the horse’s movement pattern and developing stabilizing muscles. As the horse begins to correlate his steps with the distance between the poles and their height, bad rhythm and poor quality gaits are corrected. By lack of quality we mean: uneven use of the hind legs, twisting and one-sidedness, the habit of stiffening the neck. Depending on which condition needs to be corrected, different routines can be used. The following circuits work to stabilize the hip joint, improve joint range of flexion, and eliminate muscle stiffness.

A. Snake on poles. Lay out six to eight poles so that their ends touch each other (build a long straight line). The poles can lie on the ground or be raised to a height of 20 cm. Slowly walk on light contact along the narrow serpentine crossing the poles. Your loops need to be very small so that you stay close to the line and don’t go too far. Repeat the exercise several times.

B. Fan, poles raised. Arrange five poles in the shape of a fan, raise the inner ends 20 centimeters from the ground. Outer ends should be 1,80 m apart, centers 1,20 m apart. Start by riding the inside edge of the fan in a tiny circle, slowly and slowly. Make sure your horse only takes one step between each pole. Now enlarge the circle to cross the poles on the outer edge. Try to get three steps between each pole. Keep repeating this sequence. Raise the outer ends of the poles 20 cm.

V. Poles in random order. Use as many poles as possible. Scatter them randomly around the arena (put some close together, others far away and at different angles). Now ride the arena at a walk/trot, crossing the poles. Move along a variety of trajectories, making loops, curves and zigzags. When crossing poles, ride them straight and at an angle. Work for three minutes, constantly changing the order of riding on the poles. After each scheme, take a short rest, and then return to the exercise.

When the horse’s training is going smoothly, it can be tempting to ignore the importance of procedures like those described above. But remember: every athlete must constantly keep their muscles and movements balanced and not tight. We can do this only through the constant involvement of the nervous system (outside of gymnastics). OBy paying attention to these seemingly insignificant details, we can achieve huge results.

Zhek A. Ballu (source); translation Valeria Smirnova.