What to do to get the horse to take the snaffle? (an exercise)

What to do to get the horse to take the snaffle? (an exercise)

There are many descriptions of what it should look like to ride a horse that is on the bit, biting the snaffle. There are many methods known to achieve this, and explanations of what happens to the body of the horse and rider.

This short article is not intended to be an exhaustive description of any complex processes. Rather, it is aimed at those who already know what it is about in theory, but who may not yet be able to “pull up” the practice, and are ready to experiment in order to try to achieve a result using a new method of action.

How do I feel when I put my horse on the reins?

To use the simplest words, I can say the following: I feel that the horse is moving most comfortably, bending left and right in the body and poll, and working at the most appropriate pace, it is as if he is in between “move” and the command “stop”.

Exercise to get the horse to take the snaffle

This simple, but not always easy (depending on how focused the rider is) exercise will help you experience and feel the ins and outs of riding on the reins.

1. Arrange the poles on the ground in a square so that a 12-meter circle fits into it, and there is enough space outside to make a 15-meter circle around it.

2. Walk the horse inside the square and establish even contact on two reins. Try to imagine that you are just carrying the snaffle in your hands, as if there were no cheek straps. Don’t ask anything from the horse, keep your hands neutral.

3. Now lead the horse as close to the poles as possible, asking him to follow the path of the 12-meter circle.

4. First, focus on the rhythm of the steps. You can mentally count “left, right, left, right” every time you feel the hind legs step over or move the horse’s shoulders. Repeat, a clear rhythm will help relaxation, which in turn will help with elasticity and flexibility. If your horse is moving in a direction that he normally works more lazily and reluctantly, maintaining a rhythm can help with hind activation.

5. Along with focusing on rhythm, pay attention to the position of the horse’s neck. Guide the neck with both reins so that it always stays in the center of the horse’s chest (be careful not to bend the neck in or out).

6. Focus on your upper body – keep it aligned with the horse. Do not lean in or out, do not lean forward or backward. Your shoulders should be clearly above your hips. Your spine connects to your horse’s spine at a right angle and stays in that position.

7. When you have a solid rhythm, the horse’s neck is centered on his chest and your body is vertically aligned and balanced, ask the horse to bend inward in the body with the inside hind leg deeper under the belly. Your outer leg moves back a little while your inner thigh guides and supports the movement. Imagine asking for a series of tiny leg yields so that the horse shifts its weight slightly from the inside front leg (which it will probably lean more on) to the outside hind leg. Let your hips follow the swing of the horse’s back. Be careful not to adjust to your horse’s resistance/tightness/unwillingness to bend over.

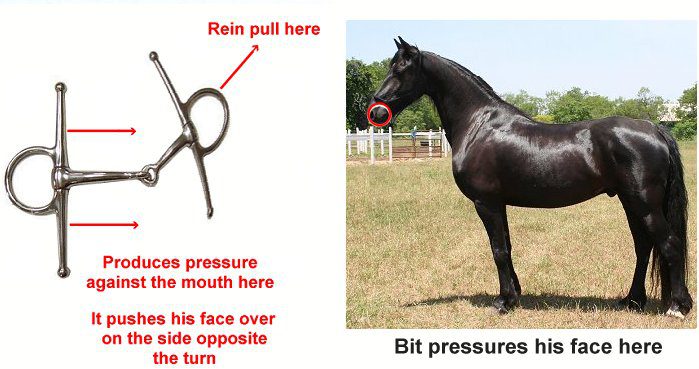

8. Ask the horse to bend at the poll with the inside rein. Do not pull the reins towards you and do not cut the horse’s mouth. If necessary, simply open the occasion. Stabilize the horse’s neck with the outside rein so that the bend is only at the poll and not at the neck.

9. Always check to see if you are allowing the horse to use his neck while moving. At the walk the neck will move back and forth, at the trot it will remain static, but also needs to be able to relax. Avoid the feeling of “holding the horse’s neck in a round position”. You need to get the feeling that you are directing the neck and poll in front of the rest of the spine so that the left and right bend is carried out depending on which rein you are on. Keep the horse’s neck in the center of the chest (if you’re not sure you can do this, have someone take a video and watch it frame by frame). Most riders tend to pull too hard on the reins, and keep the horse’s neck in so that it is almost in line with the inside point of the shoulder, not in the center of the chest. This “breaks” the line of contact between the rein and the hind leg on that side.

10 Repeat each step – checking fit, rhythm, flexion, and pronunciation. You can do this at the same time, but you can focus on each element at a time separately if that makes it easier for you.

11 Work on two reins and develop a sense that will allow you to find a position that your horse is comfortable in.

With this exercise, you bend the horse (lateral bend). Lateral bending helps to develop straightness, evenness in the horse’s body. Lateral bending encourages the horse to engage the hindquarters (increases joint flexion and buoyancy).

This gives your horse a more pronounced posture, back work, lengthening the topline, shortening the underline, you feel the horse more clearly on the outside rein, and it softens on the inside—in other words, the horse is on the snaffle, on the bit.

At first, you will find that you can maintain this state in just a few steps. Then – only on the circle 12-15 m. Take your time. Your feeling will improve. You will begin to feel how much “move” it takes to regain the lost rhythm, and how much “stop” it takes to ask the horse not to run away from the inside leg, how much flexion to the left it takes for the horse to make an internal decision, etc.

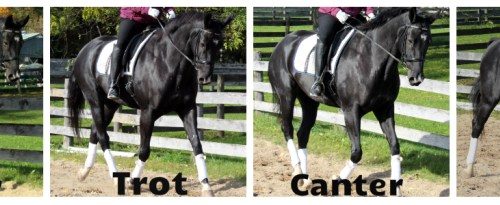

Often the rider’s seat, or the inability to keep the horse “legs ahead” while riding “straight” or in all gaits except the trot (often easier to do in the trot, as the horse’s neck remains still and the rhythm can be determined by easing), is the reason why that the horse is losing the rhythm, flexibility, connection and contact needed to stay “on the snaffle”.

You might say that it might be easier to ride a small volte at a walk and a wider one at a trot to achieve the same as described above. May be. However, I have tested this exercise with a square of poles on different riders, from children to more advanced riders on young horses, and it is the square, the need to follow a certain trajectory, that makes this exercise work every time.

Viola Grabovska (source); translation by Valeria Smirnova.