What is the best way to influence the horse with its own weight?

What is the best way to influence the horse with its own weight?

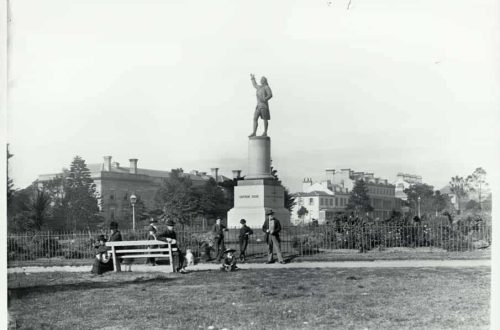

In the photo we see Sabina Ann Irbe riding her 14 year old mare Dina. They perform for young men.

This photo exudes a lot of positive energy. Dina seems completely focused on her work. She has excellent hind leg muscles. Of course, tailing may indicate some tension in the back, and this is often seen with some higher level moves, such as changes and moves that require a higher level of collection. It looks like the horse is using its tail to increase the strength of the hindquarters.

I note that if the horse tails constantly, it needs to be checked under a professional rider, single swings can most often be provoked by an annoying insect chasing a horse.

Dina carries herself. Her shoulders are raised during the gallop. The mouth is slightly foamy, and the level of contact and the angle of the lever of the mouthpiece tell us that there is good contact with the rider’s hand.

Sabina rides with concentration, the body is turned in the direction of movement and slightly tilted forward, arms and hands are in the correct position. Better when the rider is at a gallop leans forward slightly rather than leans back, so it interferes less with the horse.

When I ask myself what I could suggest to this well-coordinated pair to improve their riding, the position and contact of the rider’s pelvis immediately come to mind. I would like Sabina to better follow the horse’s movements with her pelvis – so she will help Dina move more holistically and develop more collection.

When looking at Dina’s canter stride, I notice a considerable distance between the inside (left) hind leg and the outside (right) front leg. This diagonal pair of legs land together in the canter sequence. The higher the quality of the canter stride, the better the horse can balance this diagonal.

Try to get a feel for how the horse should balance while cantering by taking a step and placing one foot slightly diagonally in front of the other. When your legs are spread, your center of gravity is lower and it’s easier for you to balance. The closer they connect legs, the higher the center of gravity becomes, and the balance becomes more fragile. Balance at a higher level (think ballet dancers) is even more fragile. It cannot be fixed or static, as it is constantly lost and restored. It’s a game in motion!

Regarding the horse, this means that the closer to each other she puts her back and front feet in the canter, the more cadence the more balanced canter will have. The rider must help the horse find balance with each new step.

Try this: Imagine that you are galloping like a horse. With each step, your feet will land farther apart and your pace will lengthen. You are moving more and more actively forward. As you change the length of your strides, lower your second leg just in front of the first – you can feel how “gathering” at the canter will feel to your horse. Your weight will shift from a more forward direction (long strides) to more lateral strides (short strides).

Your controls during the canter are very similar to this situation. Imagine that your sitting bones are your feet. And they jump on the ground.

To follow the movements of the horse while sitting on its back, the rider must balance his own weight with the weight of the horse. The horse lands on the outside hind leg and pushes off with the inside front leg. The rider’s pelvis follows this movement and during each canter stride, the outside sit bone lands first, and then the weight is shifted diagonally forward to the inside sit bone.

To influence the stride of the canter, the rider can change the direction of this weight shift from more direct to more lateral, as if you were changing stride length on the ground. Sometimes it’s amazing how the horse feels even slight shifts in the weight of the rider’s body. The rider in this case does not need to work much with the reins or legs in order to keep the canter more active and collected.

Dina’s topline appears short and slightly hollow in the area where the rider sits. The underline appears to be much longer. Understanding the importance of this diagonal phase of the canter, it is easy to make the connection that the open diagonal moment that Dina demonstrates does not help raise the back and activate the muscles of the underline (abdominal muscles).

A comparison with one’s own movements can also be useful here. Try galloping on your two again and place one hand on your lower back and the other on your stomach. When you gallop in big leaps, your lower back will be hollow and your abdominal muscles will be less engaged. As you put your feet closer together (more collected jumps), your lower back will fill up and your abdominal muscles will automatically become more active. Core is activated.

Thus, the weight transfer of the rider and the effect of this action on the horse’s canter can affect its balance, activity and ability to carry itself.

Susanna von Dietze (source); translation Valeria Smirnova.