The art of praise

The art of praise

We all want our horse to know when he has performed the action correctly – without this, he will not be able to move forward in the learning process. One of the most effective ways to let her know that we are pleased with her actions is praise. However, in order for praise to be useful and effective for the horse, we must praise clearly and pleasantly, so that the praise is perceived as encouragement.

To be effective, praise must be:

1) sincere;

2) understood and judged by the horse;

3) timely.

I believe that most of us have experienced receiving praise or encouragement, sensing their insincerity. We drew the appropriate conclusions because we noticed that the perfect action or mood of the giver did not correspond to the praise. Horses, like most animals, perfectly understand body language and feel energy. Low-energy praise and/or given by an otherwise distracted rider/handler will be less effective than praise given to someone who is energetically focused on the horse. This does not mean that praise should be bright or loud. In order for it to be effective, you must sincerely feel that a particular action is worthy of praise and, while praising the horse, focus your attention on it. This is how you ensure the authenticity and sincerity of the praise.

It will also help keep you from overpraising the horse, which makes the moments of praise less meaningful.

Our personal understanding that we are happy with the horse is not enough. The main thing is that it is the horse who understands that our praise means that he succeeded in completing a task. For praise to be effective, it must be given in a way that makes the recipient feel good…

What we may consider praise cannot be interpreted by the horse in the same way as by us. At the same time, different horses can interpret different actions as a reward.

The reward can be of two types – natural and that to which the horse need to be taught.

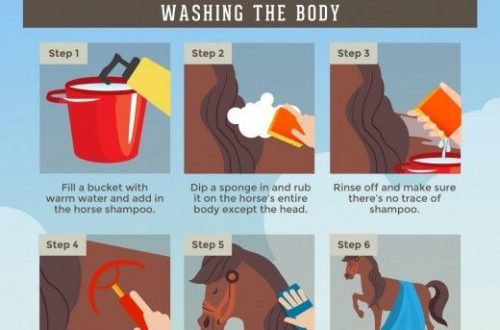

Natural praise is praise that the horse understands without training, since the very act of praise is natural to the horse. For most horses, scratching or stroking the withers or along the crest imitates and creates the same pleasant feeling that horses give each other when communicating in a herd. Usually, scratching will make the horse feel better and the tension will go away. This praise method works with most horses without any prior training.

Treats are another frequently used reward, but this is a weak reward. Horses love food, but in nature food is either there or it isn’t. The horse does not work to get food, as predators do, so for horses, the processes of labor and getting food are not connected. For them, food is not something that comes after a successful fight or hunt. However, food can be used as a motivator, for example in clicker training. Food also makes great praise when working with nervous horses, as the act of chewing relieves stress in the horse.

The horse in the picture is walking on a long rein, and the rider is scratching her withers to show that the horse has done everything right and can relax.

We often see a jubilant rider slap a horse on the neck after a successful course in show jumping or after a successful performance in any other discipline. However, such praise is not natural – horses don’t associate spanks and blows with anything positive. As a general rule, the “praise slap” is very similar to the “NO slap” that the rider uses from the ground, and this is even more embarrassing for the horse! The “commendable slap” vents the emotions of the rider, but does not provide positive stimulation for the horse. The horse may eventually learn that such actions by the rider at the end of the performance are positive, but they do not in themselves make the horse feel better.

“Bravo!” and “Good/good boy” are the two most common verbal praises. They should also not be considered natural, as there is no reason for horses to associate verbal cues with good feelings. Note, however, that horses seem to prefer higher sounds, considering them friendly. Therefore, when using verbal praise, tone of voice is very important.

The specific words to be used as praise must be accepted by the horse. The easiest way to do this is to use these words when doing something the horse likes, such as scratching where the horse is itchy. After the horse associates the words and tone with the feeling of enjoyment, the words can be used as praise. Riders should not think that the horse they are riding will recognize words of gratitude or recognize a positive tone of voice without prior training.

A key component of a successful horse reward process is also timeliness. If the purpose of your praise is to encourage the horse to repeat a certain action or movement, then the reward must be given in a timely manner so that the horse associates the reward with completing the action. A good example of riders praising a horse at the wrong time is praise after a successful ride. Usually the rider praises the horse after the last obstacle. However, this is too late, since the praise actually follows after slowing down after the last jump, or, even worse, after pulling on the reins. Verbal praise or stroking the neck/withers should be done before you pull on the reins and stop the horse. It’s even better if you can praise your horse at the right moment along the route. It is important, however, that the praise does not distract the horse.

Praise generally encourages the horse to relax, so don’t praise him when he needs to concentrate and focus (for example, in a system or moving complex combinations). In such a situation, the most pleasant thing you can do for your horse is to remain calm.

You need to make sure your horse has had time to enjoy the praise, so don’t praise him when you need to push him forward immediately – the horse will react by relaxing, and you will give him a contradictory signal.

The key to praising your horse effectively is to make sure the praise is sincere, timely, and links the activity you want to repeat in the future to the praise process itself.

Karen Nelson (source); translation by Valeria Smirnova.