Strengthen your horse’s knee joints!

Strengthen your horse’s knee joints!

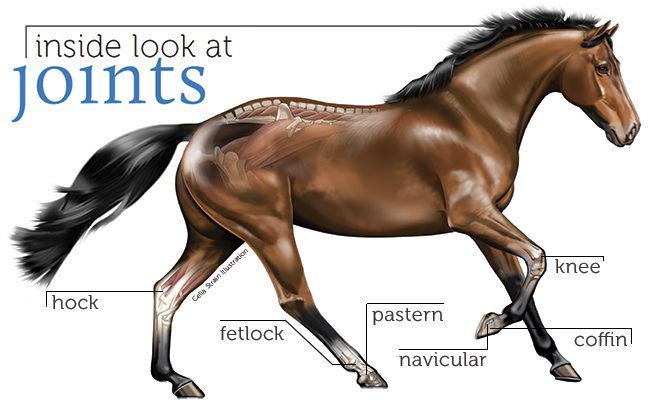

The horse knee joint is anatomically and physiologically similar to the human knee joint, but it is slightly more complex and usually more stable. Both joints use the cruciate and patellar ligaments, along with other stabilizing structures, to connect the bony framework that makes up the joint: the tibia, fibula, femur, and patella. Horses, however, have larger quadriceps, bоa large muscle above the knee, which is part of the thigh structure, and three patellar ligaments compared to only one in humans. These additional binding factors affect the unique biomechanics that allow the horse to “lock” the patella and literally sleep standing up, which is an important evolutionary advantage for the prey animal.

However, the knee joint is susceptible to arthritis, which is a consequence of the slow process of wear and tear that occurs as a normal consequence of sports activity and/or as a consequence of more severe traumatic actions in the soft tissues. Soft tissue injuries such as cruciate ligament or meniscus injury are generally less common in horses compared to humans due to the increased stability of the horse’s knee joint. However, these problems are serious and could lead to the end of her sports career.

Who is at risk?

Ligament injuries in the horse’s knee joint are usually the result of a combination of the effects of speed and rotation: awkward pushing or landing while clearing obstacles, sudden stops, abrupt and rapid changes of direction, and other mistakes that the horse makes while moving at speed or out of balance. In these cases, the horse’s attempt to unevenly load the isolated parts of the knee joint can overstress some of the joint’s stabilizing structures, causing injury. Dressage horses that do not work at high speeds can also be susceptible to these injuries because the demands of their sport involve flexion and rotation that compromise the knee joints.

But it’s not just sports tournament horses that are at risk of knee injury. Can be injuredAny horse, for example, as a result of a targeted kick to the knee, a slip, a fall, or a problem with wet, swampy, hard ground. In fact, most ordinary horses, weaker, less physically fit, often overweight, suffer from knee injuries more often. Unevenly developed underline and core musculature, along with a general lack of good conditioning and tone, place these horses at high risk. Poor foot care and unbalanced riding exacerbate disproportion, asymmetry and potentially lead to injury.

Young horses are especially vulnerable during growth spurts (periods of rapid bone and body mass development characterized by uneven growth of various structures) as their ligaments often become stiffer or weaker depending on the changing angles of the bones and joints. Because the knee joint is made up of four bones and various ligaments, this area is often exposed to risks during skeletal and muscular development. As the bones of the joint grow in a young horse, the tendons and muscles may need extra time to “catch up” with each other, growing in size and strengthening.

During these periods, riders often notice that their previously unproblematic horses become “weak from behind”. They may start more often stumble, the rear begins to lag behind the front, the knee joints can even make sounds and clicks. When working downhill, riders on these growing young horses may feel a general unwillingness and inability for the horse to maintain a straight line (the horse will attempt to go downhill at an angle). Although these symptoms sometimes indicate structural problems, they are most often signs of weakness.

Walking and stretching

Careful progressive work to strengthen the knee joints can help protect them from injury. It is especially important if the area is already weak due to build, lack of fitness, or other factors. If the horse is obviously lame, if the joint is swollen, if it is tender or painful, contact your veterinarian to rule out any medical cause before starting a strengthening program.

So, what to do to strengthen the knee joints?

1. Increase your total daily movement. Give your horse the opportunity to spend as much time as possible in the levada, ideally in a rolling pasture, in the company of other horses (horses tend to be more active when grazing in company). If you are feeding your horse hay in a levada, spread it out over several troughs so that he has to move more actively.

2. Do stretching exercises. While doing these exercises, keep your personal safety and the safety of your horse in mind. They are best done on a flat, stable surface. It is desirable (especially initially) to have a helper nearby, holding the horse on a free but controlled lead.

With each of the following exercises, lift the horse’s hind leg off the ground and stretch it as described until you feel a slight resistance. Hold the stretch for 10-20 seconds, then release your leg. As the horse gets used to the stretching procedure and feels comfortable during it, you can work on gradually improving the range of motion.

- Flex the hip and knee of the horse, lifting the hoof up and inward, pulling it towards the midline of the body (similar to checking the hock joint by a veterinarian). Then, while the hoof is up and the leg is bent at the hock, pull it out from under the horse’s body.

- Pull the rear foot forward, towards the back of the carpal joint of the horse’s front leg on the same side.

- Pull the hoof back by extending the back leg in the same position you use when you take the leg out for the hook. Push slowly, relaxing your horse will eventually allow you to expand your range of motion considerably.

Another great way to start stretching and getting the horse to use his knees is with a good working stride move that requires the horse to balance on each leg and use his quads to push forward. This, in turn, strengthens the muscles and ligaments. Ask a dressage instructor or other specialist to show you how to properly round the horse’s frame and encourage him to step with his hind legs under the center of gravity (bracket). Be aware that this may take some time as a weak untrained horse will have difficulty reaching the proper frame. However consistent, correct slow operation over time will bear fruit.

Stretching

Step 1. I flex the horse’s hip and knee joint, lifting the hoof up and forward. As you flex your knuckles, help your horse balance by keeping the lower leg away from the midline of the body and shifting its weight onto the skating leg. Each stretch should last 10-20 seconds. As the horse gets more comfortable, you can work on improving the range of motion.

Step 2. While the hoof is still up and the hock joint is flexed, push the point of the hock joint towards the midline and at the same time draw the hoof sideways or away from the midline. This movement rotates the knee and strengthens and ultimately strengthens the ligaments and the medial, or internal, support structures of the knee joint. Reverse exercise – pull the hock point outward, and the hoof medially or inward, turning the knee in the opposite direction. This serves to reinforce the lateral or external support structures.

Exercises on the ground and in the saddle

Ground exercises

1. Have your assistant hold the horse, and you stand 1-1,5 meters behind, perpendicular to his hips, and grasp the tail. Gently pull it towards you until you feel the horse resist the pressure and back off. You will notice how her back, abs, and importantly, her quads tense up as she confronts you. Maintain pressure for 10-20 seconds and release. Repeat this exercise 10 times on each side.

2. Walk your horse up and down small slopes at a walk in your hands. Ask her to walk slowly and keep a straight line without letting her move sideways. This will require balanced use of the knee joints. Stop your horse periodically – this strengthens the front of the quads and patella – then ask the horse to move forward again.

This exercise is especially useful in the hands as the horse can focus on his balance and movement without compensating for the weight and position of the rider. As with all other developmental exercises, doing this exercise incorrectly is almost useless and can even harm the horse, so try to keep everything right and simple.

Walking in the hands downhill is a great exercise that encourages the horse to use his hindquarters and work the muscles and structures that support not only the knee joints, but also the loin and croup. Make the horse walk in a straight line – don’t let him lean to the left or right, encourage him to consistently load each leg throughout the range of motion. This will require balanced use of the knee joints.

3. Lunging on slightly sloping terrain strengthens the ligaments and muscles on the inside and outside of the knee joint as the horse circles. Find a place in the pasture where the flat terrain turns into a gentle hill. Stand so that the horse runs half the circle on a flat area and half on a hill. To get up the hill, your horse will use the extrinsic quadriceps muscles. These muscles support the knee. The ligaments that enter the apparatus of the knee joint can be developed and strengthened by working on such terrain.

When descending a hill, your horse will use the internal quadriceps muscles. The internal and external muscles of these areas are difficult to work out and trainers must use lateral movements to strengthen them. Lunging downhill is well received by horses and has the added benefit of achieving balance. Insist on the horse maintaining a steady pace so that he doesn’t roll in or out.

Note. Our model in these photos is very calm and has a lot of experience in lunging, so she is wearing a halter. If your horse is more energetic or active, use a bridle, a lunging cavesson, or whatever harness is comfortable for you.

In the saddle

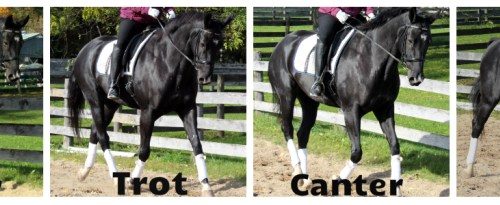

1. Focus on the walk-trot transitions, trot-canter transitions, walk-canter transitions, etc. Always try to keep transitions smooth and balanced as this strengthens muscles, ligaments and improves movement.

2. When you are working a horse in an open area, instead of moving in long, straight lines, make small serpentines that require the horse to flex and engage the internal and external leg muscles—mainly the quads.

3. If you have access to an area with deep sandy ground (such as a beach), train there. Please note: prolonged hard work on such ground can lead to injury, so increase the difficulty and duration of training very gradually. As the horse gets stronger, focus on the shapes that also primarily use the medial and lateral quadriceps—circles and spirals.

The rider moves the horse in a good working trot, making sure she engages her hindquarters and pushes herself with her hindquarters, lifting her back. This will help build muscle and strengthen the ligaments of the knee joints.

Riders tend to overload the horse with strength training at first. Regardless of which exercises you decide to include in your workout, it’s important to progress slowly and in stages. Build a long-term program, start with short, easy sessions, and never increase the intensity and duration of exercise at the same time.

For example, if you start with 15 minutes of lunging on flat ground, including a warm-up, stepping back, and a few changes of direction, repeat the same program in your next workout. If your horse completes the task easily, add three to five minutes of work. Continue to gradually increase the duration of work over seven to ten workouts until you reach 30 minutes or more. You can then decrease the duration on a given day and add some hill work (increasing intensity), such as 10 minutes of lunging on flat ground and eight minutes of walking up and down hills. If your horse starts to struggle and resist, you can simply go back to the less intense work that you were previously able to handle easily and stay at that level for a while before trying again. increase the intensity.

Add these strengthening sessions to your regular workout routine for at least three days a week, but preferably four or five. Always keep track of the time of each session, avoid overworking the horse, especially when the work is going very well. Keep a record of your program and control the intensity and duration of your sessions. This will help you plan your progress and decide when to increase “tension” and when to give your horse a training rest. Both are very important for improving physical fitness.

Through methodical training, patience, and attention to exercises that target specific muscles and ligaments, you can strengthen your horse’s knee joints and lead to a happier, healthier racing career.

Kenneth Markella (source); translation by Valeria Smirnova.