Rider hand position: correct and incorrect

Rider hand position: correct and incorrect

The eminent athlete and trainer, Olympian Jim Wofford, gave an excellent description of the rider’s hand positions in his book Training The Three Day Event Horse and Rider.

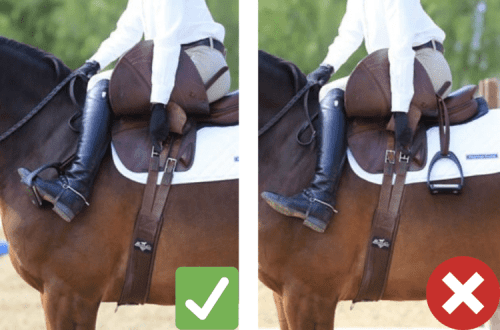

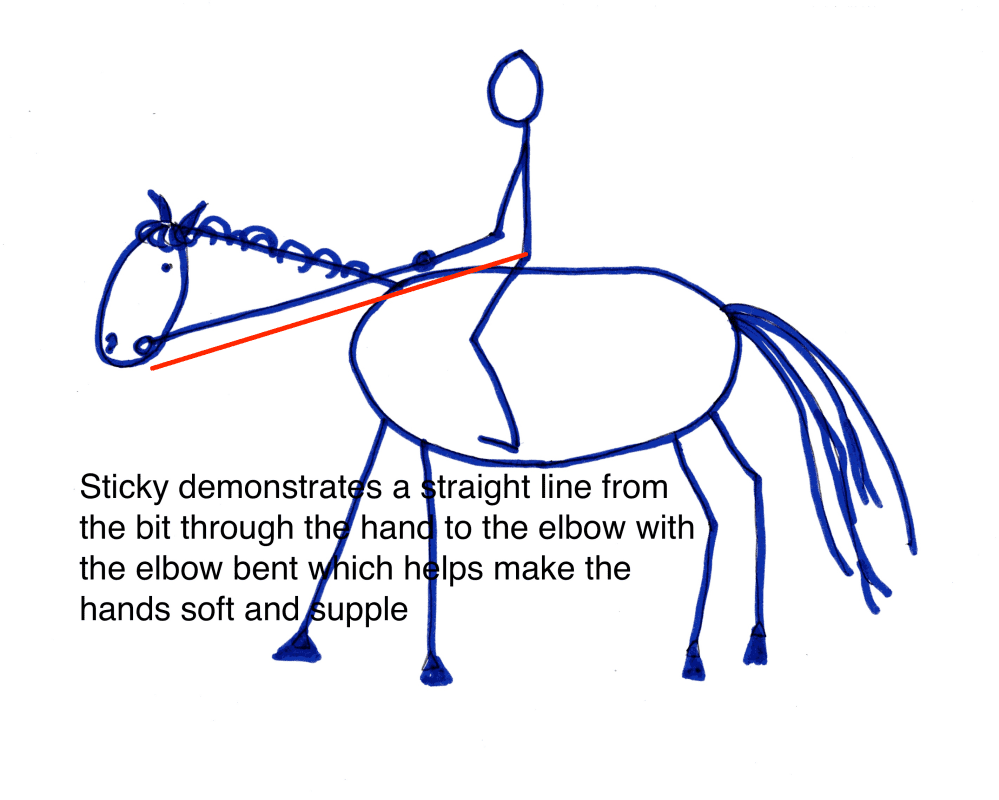

We see a straight line from the elbow to the horse’s mouth. The elbow is bent, which allows the hand to be soft and supple.

“Your arms should form a straight line to the horse’s mouth. Thumbs – on top of the reins, slightly turned inward from the vertical, elbows close to the body. The forearm, wrist and fingers form a natural straight line from the elbow to the snaffle.

Note that this line will change as the horse progresses. As the horse’s head and neck rise, the rider’s forearms will also will rise above the withers. However, the straight line should be maintained.

The position of the hand is determined not some artificial measurement, but rather the level of training of the horse. A very young horse will naturally carry his head and neck quite low. It should be encouraged, not hindered. You compensate for this position of her head and neck by the fact that your hands are also in an extremely low position. If the horse is already well prepared and in high collection, the rider’s forearms may actually be above horizontal, but a straight line from the elbow to the horse’s mouth still should persist.

It is not correct to say that the rider has good hands. Good riders have good elbows and good shoulders! The range of motion of the hands is limited. They can either gain or soften the rein. And that elastic feeling that we are all looking for is created by the elbows and shoulders.

Tension in the shoulders and lack of flexibility in the elbows encourage the rider’s arms to follow their body rather than the movement of the horse’s head and neck. Rigid shoulders and elbows hinder the rider’s ability to move their arms naturally by limiting the elastic connection to the horse’s mouth.

Much depends on the type of horse, the level of training and the body structure of the rider. The rider’s hands can be described in many terms: good, cruel, soft, passive, interfering, etc. The term “good hands” is also used here, describing the hands that are soft, do not hurt the horse and allow him to do what he asks.

But why don’t all riders have “good hands”?

The quality of the rider’s hands depends on the quality of his seat. It’s impossible to have good hands if you don’t have a good fit. A good seat allows the rider to cushion and balance without having to lean on the reins. A good seat is also important in order to help the rider not tense up in the shoulders. It takes hours and hours in the saddle to create an independent seat.

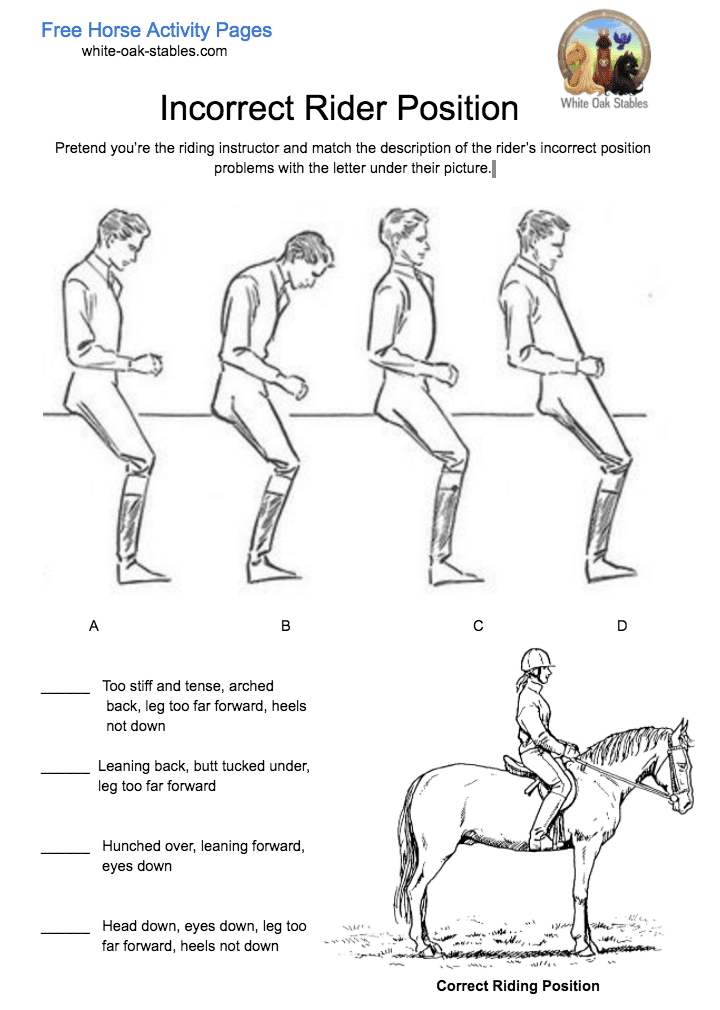

Riders who think that hands are just hands.

Some riders think that soft hands are flexible fingers and wrists, not relaxed hands. They fix the upper part of the arm and perform bоmost of the work by bending the wrists and opening and closing the fingers. These riders tend to have a tight upper body and stiff, tight shoulders. They are recognizable by their low-slung arms, somewhat rounded shoulders, and a downward-sloping head.

The rider who holds the reins in his free fingers does not have good hands, he simply runs the risk of the horse taking the reins from him.

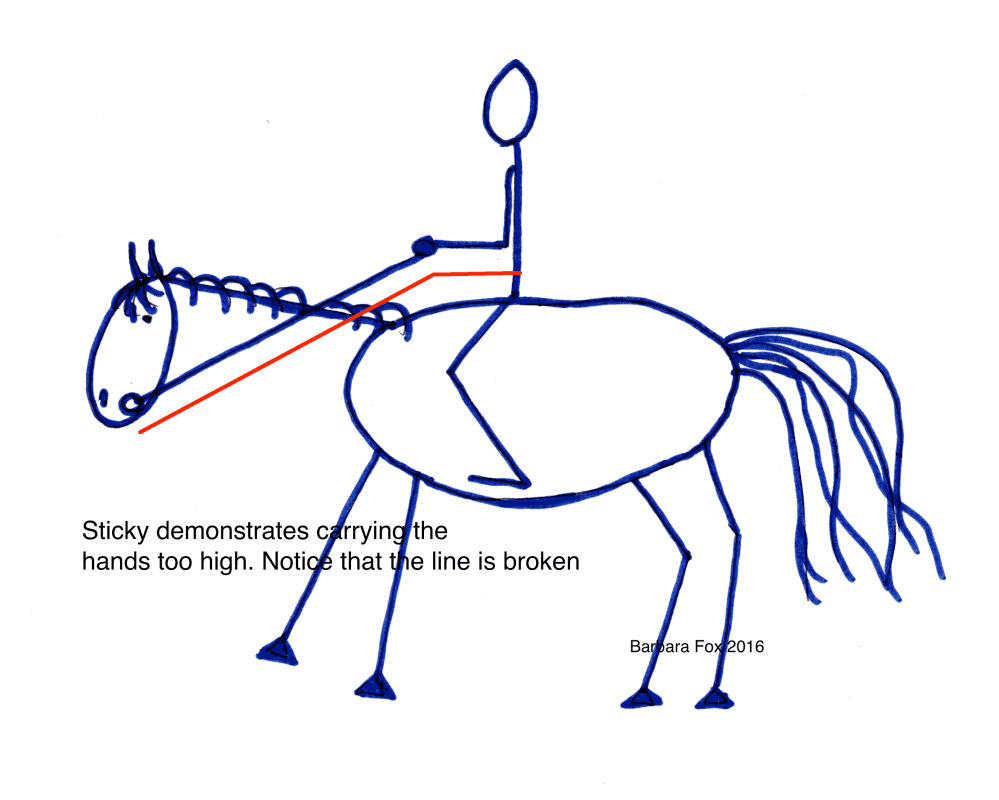

Hands raised too high

If the rider holds his hands high and breaks the imaginary straight line, then this is either the result of illiterate training or the rider’s lack of understanding of how the bit affects the horse’s mouth. The rider learned to hold his hands at a certain height above the withers and at a certain distance in front of the saddle, but he was not taught anything about the mouth of the horse and about the function of the hand.

I see this more often among riders who have not been taught enough dressage lessons. They were taught to keep their hands up and in front of them (carry their hands in the air) with the obvious hope that the horse would soon join them and take the reins and so. This can be good if we are talking about a top-level horse, working in a bridle, on which a professional rider sits deep in the saddle. with excellent leg. But such a hand is completely unsuitable for mediocre riders and horses.

The rider holds his hands very high, breaking a straight imaginary mouth-elbow line.

If you have a chance to look at the illustrations from Rainer Klimke’s book Basic Training of the Young Horse, you will notice that in almost all the pictures the riders keep a straight line (snaffle, hands, elbow). The rider’s arm is lifted when raised in front of the horse. It follows the lifting of the neck and head, and not vice versa. It is also interesting to note that in most cases the horse’s nose is not much higher than the rider’s knee.

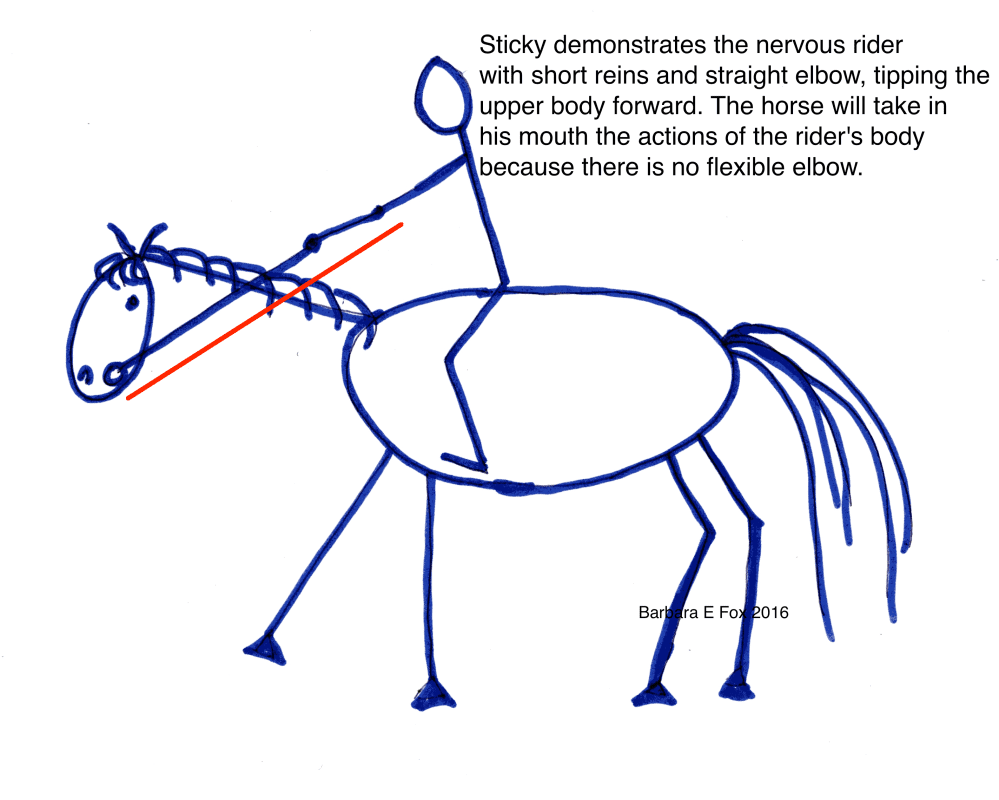

hard hands

In the illustration we see a nervous rider. The rein is short, the elbow is straight, the body is swamped forward. The rider’s swings are reflected in the horse’s mouth because the elbow is not elastic.

If the rider has a short rein and a straight arm without a bend at the elbow, this may indicate fear – the rider is afraid that the horse may start to goat or blow.

This rider leaves absolutely no room for error and movement. Every vibration of his body echoes in the horse’s mouth. This is because the hinge (opening/closing) of the elbow is not working.

The rider falls on the front, is in front of the horse’s center of gravity and risks falling through his neck if the horse begins to goat.

This hand position makes a nervous horse even more nervous, and therefore even more frightening to the rider.

Such a rider must be persuaded to lengthen the reins, bend the elbows, and mount vertically in the saddle.

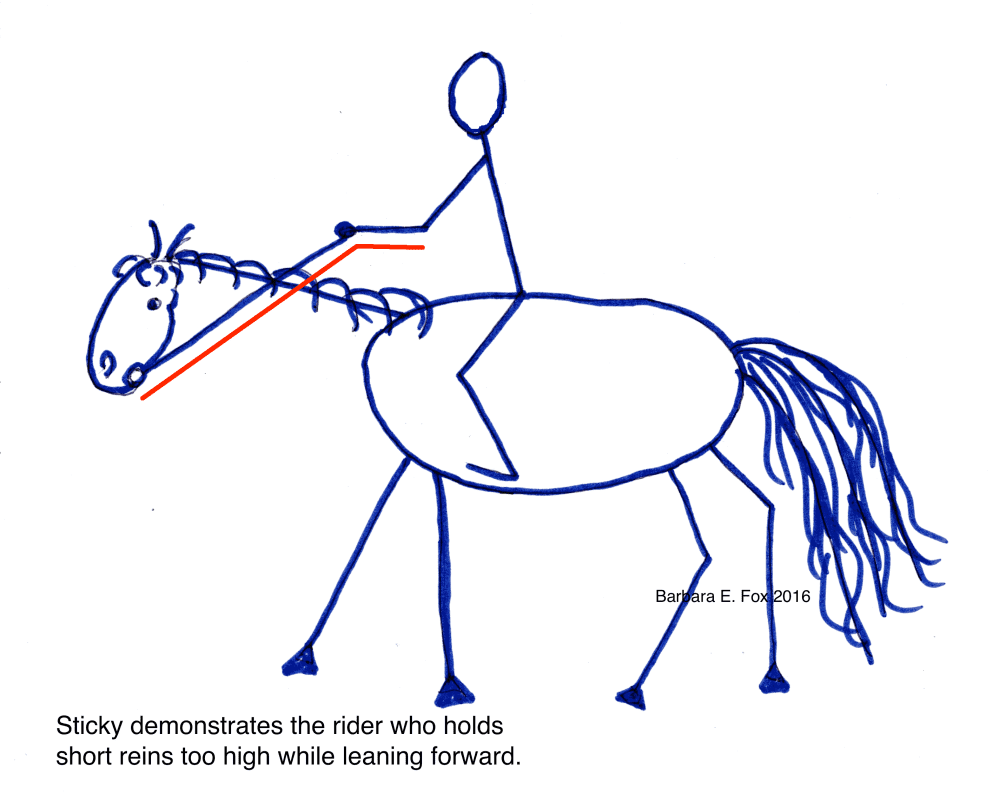

Hands up and in front

The rider holds the hands high, the reins short and leans forward.

Hands held high and in front are usually held by a rider who has received very little instruction and is fearful, among other things. A combination of fear and lack of knowledge.

You will notice that the rider is constantly adjusting and picking up the reins, picking up even more, especially during ascending transitions into the trot.

This rider will also lean forward, putting himself in an unstable position. He should be encouraged to lengthen the reins, sit deep and drop his arms.

nervous rider

If the rider is afraid of a certain horse, it is better to remove him from it. A shy horse will not respond positively to a tense, nervous rider who keeps the reins short, arms high, and shoulders tight.

Sometimes the rider’s fears are general and do not depend on which horse he rides. You can help this rider by praising him and encouraging him to lengthen the reins. Lunging lessons can help correct hand position and develop a good landing. Try to adequately assess the requirements for such a rider and set achievable goals for him, setting him up for success.

A little about stress

Tension in one part of the rider’s body will cause tension in another part of the rider. It is very good when your student shows a good straight line from the elbow to the horse’s mouth from the very beginning.

Check if his back and shoulders are tense. The rider may have tense shoulders even before getting into the saddle – this is one of the parts of the body in which a person accumulates stress. The more stress in his life outside the stable (at work, at home), the more tense their shoulders are during the ride. If we add to this the wrong position of the hands and compensation for the lack of seating, we get a rider who is kicked off the saddle and who hangs on the rein. Stretching, relaxation, and breathing exercises can help manage this tension. Maybe even a massage.

Students who are afraid of falling will cling to the reins. Of course, you can keep your horse from bucking with your hands, but they won’t help you stay on top. Only the right posture can help you. An independent landing is potentially good hands. (I’m talking about potential because not all riders with a good seat have good hands.)

Free movement forward

Rigid, enslaved, grasping, frightened hands do not allow the horse to go forward. It’s like slamming a door in her face. In such a situation, some horses will become nervous, while others will become irritated and angry.

If your student complains that his horse is lazy or does not move forward freely, is behind the legs, or needs spurs and a whip, take the time to analyze his handwork. Sometimes changing the position of the rider’s hands changes the horse.

Barbara Allyn Fox (source); translation by Valeria Smirnova