Reasoning about punishment

Reasoning about punishment

Followers of the Hindu religion believe that the god Ganesha gave elephants to the service of people, and in order for the elephants to do everything that is required, he made them submissive. Elephants are much more dangerous than horses, and the death rate among the Mahouts who drive them is much higher than among people associated with horses. Therefore, when “training” young elephants, people tie them up and torture them with sticks and spears until they stop resisting. To make the animal weak, they do not give him food, and sometimes water. A few days later, the young elephant is taken out and secured between two adult elephants, on which the riders sit (the rider also sits on the young elephant). All riders simultaneously give clear signals to their elephants, including the young one. These are the signals that the elephant must respond to. Within a few weeks, the young elephant begins to understand what the signals mean. When, for example, riders give a stop signal, the big elephants stop and stop the young elephant, so that he begins to correlate the signal and the action that he “performs”. Elephant at once is learning correct responses to clear signals, but in what a brutal way…

My story sounds wild, doesn’t it? But sometimes when we look at the work of refined, civilized riders and trainers and their interaction with their horses, we see that they are not far removed from the Indian Mahouts …

I often think that the biggest problem with many horse owners is that they believe that the horse knows what he is supposed to do, that he understands what he is doing, that he is aware of his behavior, that he knows right from wrong. And here one should introduce a kind of presumption of innocence: if the horse does not do something, obviously it does not know or does not understand what you want from it. Be consistent and persistent as a trainer and the horse will learn everything.

Whatever the horse does, it is either “beneficial” to it or it is not. If you convey to the horse that the behavior required of him will be “beneficial” for him, then he will demonstrate it with a desire, and over time this behavior will turn into a habit.

Horses are not the same – some are more difficult than others, and I think that’s why, in the early stages of training, we must use gentle but persistent pressure and softening with all horses. I am convinced that the main difference between the so-called “good” and “difficult” horses is the result of what we reward at an early stage of learning. A “good” horse gives the correct answer and is rewarded for it, while a “difficult” horse is rewarded for the wrong answer – so the trainer himself exacerbates the problem. I’ll explain. If the horse does something we don’t want, say candles, and we soften the pressure, then we reward the candle. Or, if she backs away, we soften the pressure and teach her to do things we don’t want to do again. We need to make sure that we only reward the behavior we want to get.

See how the so-called “difficult” horse is “born”: someone touches the croup of the foal, the foal beats back and runs away. In doing so, he learns an important lesson: when people touch you, you run away, and it works – the person no longer annoys you. Then the same horse is taught to walk on the bit or to lead the rider: the horse reacts incorrectly to something (bounce or back away), and the rider releases pressure – and here he again inadvertently teaches the horse the wrong reaction. From the horse’s point of view, he’s doing the right thing – he’s learning just like a “good” horse who happens to go ahead when the rider first leg-pushed him. A horse that is on a “good” path will be loved by everyone, while a “difficult” horse will be “nurtured”. But in fact, both of them react the same way, just one was awarded for “good”, and the second – for “bad”.

The most common reaction is to punish the horse for what he did. It is based on our belief that the horse knew what he was doing, assessed his behavior as wrong, but still showed it.

A good coach, on the other hand, would think: “What is the goal of training and how can I best achieve it? How do I use my operant conditioning tools—negative reinforcement, positive reinforcement, or punishment?”

Even if you use negative reinforcement, it still comes down to pressure and release. At what point and in response to what behavior will you ease the pressure? How do you build pressure by teaching the horse one “variable” at a time? This approach should be the most important part of the early training of the horse.

We must make sure that all our actions are clear. How is the first resistance formed?

Most books on horses and riding since antiquity rarely mention how to train a horse to respond correctly. The focus is more on rider fit than actual training tools. The seat is, of course, important in order to give the horse a strong and clear signal, but he does not train. Let’s take the German scale of learning as an example. Her first “step” is rhythm/relaxation. But after all, even to this stage, the horse comes already trained in the answer. Rhythm simply perfects it, and relaxation is its essential characteristic. Imagine a piaffe. You need to know how to prepare for it, how to get a basic answer, how to take a step away from it, how to get smooth progress, etc.

We must admit that the horse is not distinguished by outstanding intellectual abilities. They’re smart as horses, but they’ve never had to try to outsmart their dinner or run into the trouble of fruit and nut-eating animals that have to figure things out to get to the pulp. Yes, you can immediately talk about smart horses that open gates or even release other horses. Yes, their actions are smart, but this is Operant conditioning, not reasoning. Whatever experiments we do, horses are not up to the level of dogs, or chimpanzees, or dolphins. And they are not animals originally seeking cooperation with us. In any case, we need to be clear that when we start teaching members of another species, we must be careful not to hope for a miracle and not to think, even implicitly, that we must act as if we are teaching another person.

What are the principles of working with a horse, having a negative experience of early training?

1. The horse must be trained to work on the ground so that the possible confusion and ambiguities present in work on the ground do not carry over to work under the bridle.

2. We must know the signals we want to teach the horse.

3. We must be sure that all signals used are different from each other so that the horse can tell them apart.

4. Every effort should be made to signals do not overlapbecause some of the controls are very similar to each other. For example, a hand action that “rounds” the horse or a stop on one rein can be similar to an early command to stop and turn, respectively. Therefore, care must be taken that the horse distinguishes them.

5. There should be no exceptions to your rules! We cannot expect horses to have the intelligence to handle exceptions.

Horses interact with each other in a language they understand. Therefore, if a person can communicate with a horse in the same “understandable” way, giving clear signals, then the horse will “hear” him, as he hears his relatives.

I’ll give you an example. I teach people to tell the horse to move forward with a lead or rein before stepping forward with their foot. Then, if they feel like it, they can add another command, such as a sound (“forward”) or, as Georgia Bruce does, raise a hand. Any of these commands will be helpful. But we have to make sure we don’t take the first step or stop first, otherwise we’re laying a small but heavy brick in the wall of confusion (the horse may take the movement of our legs as a command to move).

When the horse receives clear signals that never deceive, including teaching him to stand still, he becomes much calmer. She doesn’t care what your feet are doing. I’ve corrected a lot of nervous horses just by being clear to them.

I have used this technique in my work with elephants as well. It really helps to make a confused animal sentient again. These principles are important to get started in any training system you follow. Make sure you are clear and consistent and that your signals do not overlap. They must be different for different teams, there are no exceptions to this rule.

And another rule to which there will never be exceptions is not punishing an angry horse.

We know that violence makes people “stronger”, more confident. It makes us feel that this is how the problem can be solved. When you have a hammer in your hand, all problems start to look like nails. One other thing we know about punishment is that punishment can create a rather insecure relationship between the punisher and the punished. Horses have a fantastic memory, especially for something that once scared them. Therefore, once a problem has arisen, it may haunt you for a long time in the future.

You really should avoid punishment and in no case allow the horse to be afraid of you. Punishment reduces the animal’s ability to generate new responses, so in difficult situations (when you ask a horse for difficult answers), the horse is less likely to try to get to the heart of the task and more likely to become nervous, like a child who was punished or humiliated at teacher’s school , will be afraid to raise his hand even when he is sure of the correctness of his answer.

The difference between Punishment and Negative Reinforcement may seem blurry at first glance. And it is that negative reinforcement helps to reinforce the desired behavior – you soften the pressure when the horse answers correctly, you try to project the correct response. Punishment is meant to remove (!) behavior: if the horse hits you, you hit it…. but how easy it is to overdo it. I’d rather find out why the horse hits or bites.

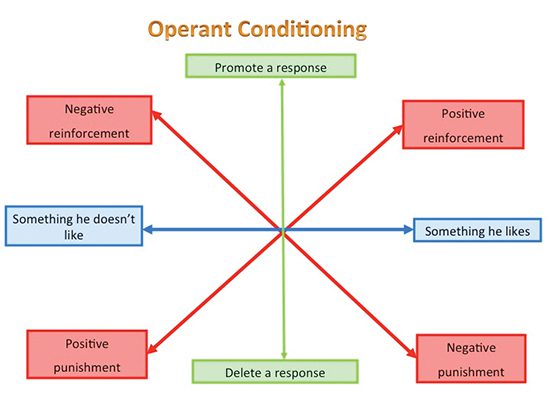

I want to bring to your attention a diagram describing operant conditioning:

operant conditioning: Facilitating response Delete answer; Negative reinforcement Negative punishment; Something the animal doesn’t like Something the animal likes; Positive reinforcement positive punishment.

This diagram shows us four forms of operant conditioning—negative reinforcement, positive reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. If you look at the horizontal axis, you will see two blocks – what the horse likes and what he doesn’t like – attractive and unattractive stimuli. Rein and legs can be unattractive stimuli, and delicacy and caress can be attractive stimuli.

On the vertical axis, we see two blocks with answers that we want to see with a higher (top) or lower (bottom) probability.

Positive means addition, negative means subtraction. So now we have four blocks. Positive reinforcement uses attractive stimuli to make a response more likely (for example, when working on a piaffe, the clicker method is used).). Negative reinforcement uses unattractive stimuli to also make a response more likely (for example, softening the leg as the horse moves forward). Positive punishment works to remove the behavior (for example, the horse gets hit with a whip when it hits), and negative punishment removes something attractive (to remove the response – we move away from the horse when it starts to dig).

We have used this scheme in our recent studies. At the University of Sydney, Melissa Starling, PhD, a student of Professor Paul McGreevy, studies how arousal (vigilance) and emotional state interfere with learning. So, it would be useless to try to train a horse if it was locked up all night. in the stable, and therefore was too excited. Likewise, it can prove to be very difficult to drive a ride due to the high level of arousal and the negative emotional state of the horse, if she had a negative, frightening experience in a certain place.

Of course, coaches have always known that arousal levels and emotional impact affect training. The most interesting thing about this study is that we make accurate predictions about the usefulness or insufficiency of a particular type of training (negative or positive reinforcement or punishment) under certain conditions (arousal, emotionality).

Andrew McLean, PhD, Head of the Australian Center for Equine Behavior Research (source); translation by Valeria Smirnova.