Point of view: what are the signals for the horse and what are the controls?

Point of view: what are the signals for the horse and what are the controls?

Terminology and its use often generate a lot of controversy. There is a discussion in the horse world about controls and signals/cues. So, for example, some instructors say about using the legs as a means of control, and others about giving a signal / prompt with the legs. The students are confused.

The horse doesn’t care what the trainer calls what he needs to do. It is important for her to understand him from the point of view of her horse logic.

Teaching method, “Attention to the rider” (from the verb “heed” – approx. ed.), which I espouse, uses methodically applied directional pressure options to create behaviors. The pressure that creates forms of behavior is called the means of control. When the horse understands what form of behavior you want from him by applying a certain pressure, you can associate with this form signal or hint. Now you can use this signal to tell your horse exactly when you want something from him. You teach horse using the controls, and ask – signals and hints.

What do we include in controls? Pressure! When you apply it, you indicate the direction you want the horse to go and apply it methodically and consistently. This is not the same as if we were talking about persistent or forced or repeated application. Many people are just being rude to horses rather than using the controls. Instead of touching the horse with the whip or simply pointing at it with the tip of the whip, they beat it. Rudeness and rudeness certainly have an effect on the horse, but they do not teach him.

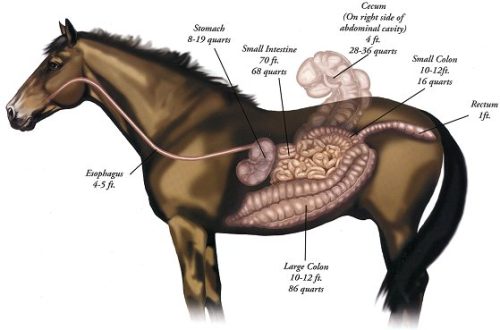

The means of control must be logical for the horse. The horse reacts to it in a predictable way that is natural or instinctive for him. So, for example, if you start approaching the horse from behind, he will somehow turn his head to see what is happening. If you are a little to the left of her, she will turn her head to the left to be able to follow you, if a little to the right, then to the right.

If you approach too quickly, or if your horse is just shy, he may walk away first and only then wonder what happened. If the way forward is open to her, she will go in that direction. If not, the horse will turn around, turn and walk away in any direction it deems open. Once she’s far enough away to feel safe from what she perceives as a threat, she’ll turn around to get a good look and find out what’s going on. These are the horse’s logical responses to the pressure you have applied by approaching from behind.

signals are conditioned responses that are not necessarily logical for the horse. They are supported by encouragement. You use pressure to create the desired form of behavior. You give the horse a signal as soon as he has created this form. Then you reward her with a scratch or something else she likes, so you tell her what you wanted from her. Eventually you can stop using the controls because the horse will respond to you as soon as he gets the signal and look for his reward.

Once the horse understands that a particular signal requires a particular form of behavior from him, it will no longer be necessary to use the controls to obtain this form. Teaching a horse to respond to signals, rather than just a means of control, is like replacing a manual transmission with an automatic transmission in a sports car. Now anyone can manage it. The signal is what the trainer can sell with the horse. The owner will be able to ride and signal the horse without having to understand all the intricacies of the controls to get the behavior he wants.

What happens when you stop supporting a signal with a reward? The horse will begin to back away from the learning curve. She first learned that she gets a reward when she gives you the right response to a signal. Now she gives you a response to the signal, but does not receive any reward. Pretty soon she stops giving you the right form, the answer, because she won’t have a logical reason to do it.

When you give a signal to a horse, you must watch his response to it. If the horse is ignoring the cue, you need to go back to the control that was used to teach the horse the particular form of behavior and remind him of the connection between cue and form. Retraining horses that have stopped responding to signals is what helps trainers stay in the business.

“Control” is pressure, which helps the horse understand what kind of behavior you are asking him to do, or in which direction he needs to move, or the amount of energy you would like to get from him.

When we start training a young horse, we first develop a sense of rhythm and relaxation in him that will help him feel safe around us, and then we begin to create corridors of pressure around him that help him understand exactly what we would like to see. she did. The horse must learn that when he responds correctly to pressure, the pressure is released. The key meaning of these “pressures”, or controls, is that you can modify them.

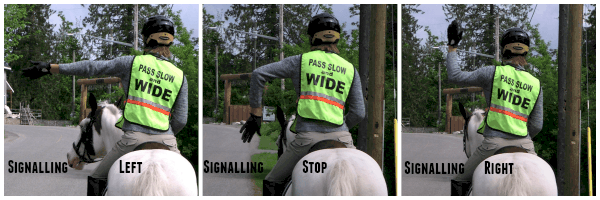

Once the horse understands what you want him to do, you can use signals or “cues” that tell the horse what you want him to do. Signals cannot be changed. They are like switches that can be either on or off, to do or not to do something.

The horse establishes relationships between prompting and execution of a certain movement at a certain speed in a certain rhythm, etc. Professional trainers (bereytors) use the controls to develop the horse, then they put signals/cues on top so that amateurs can ride these horses and get the coveted rosettes.

Some people try to train a horse by giving it a signal and then finding a way to get it to do what they want until the horse finally associates the signal with the activity. For example, one might want to train a young horse to walk side by side on a loose lead lead. One trainer will perform “shamanic dances” by taking giant steps or twitching the lead and hoping the horse will follow. These are signals/tips. another coach will do otherwise. He will stand next to the horse in the direction of travel, holding the whip in his outer hand, and begin to move it slightly to encourage the horse to move forward. If that doesn’t work, the trainer can change the motion to be a little louder or faster, or even touch the horse’s thigh with the tip of the whip to show the horse that he wants to go forward. The coach may lean forward slightly. Or stand slightly behind the secondary line of influence that runs across the horse’s shoulders, perpendicular to his spine. These are controls. When the horse starts moving, the trainer will move with him in the same direction and at the same pace.

When the horse begins to understand what the trainer wants from him, he fulfills the request in response to his movements, such as the movement of the foot, or the compression of the legs, or the movement of the seat. The horse creates a connection between a particular corridor of controls and the desired behavior. And this is where the line between controls and signals/hints starts to blur a bit! However, the fact remains that the corridor of controls can be changed and transformed. A signal or prompt is just a “do it” button that cannot be changed or transformed.

When new students come to us for training, they tend to misunderstand the difference between controls and signals. When they take a step towards the house and their trained horse steps along with them, they think that the very step induces the horse to follow them. So they try to use the same pattern with the new horse. When they discover that this signal, which their trained horse understands perfectly, does not make sense to a young green horse, they begin to learn a method of using controls to encourage the horse to walk.

When people use signals long enough, they can forget that the signal doesn’t make the horse do anything. A signal is simply an on/off switch for a particular behavior, originally developed through the use of a corridor of controls. In the case of amateur riders and professional trainers, the former may never be faced with learning the corridor of controls.

The problem is that over time, the horse’s response to a signal or cue can become boring. When this happens, the signal becomes meaningless and there is no way to enforce it. Repeating the signal over and over again just makes the horse respond dimmer and the trainer and rider become frustrated.

Pavlov realized this many years ago when he did a classic study of conditioned responses in dogs. He wanted to use a response that the dog could not directly control. He used salivation because he could easily provoke it with food. Pavlov gave a signal with a bell while feeding the dogs, and soon discovered that at the sound of the bell dogs salivate even if there is no food nearby. He made all sorts of graphs of how much saliva each dog produced in the presence and absence of food. The scientist found that each dog has an individual learning curve for the relationship between the sound of the bell and food intake. When he continued with the main experiment but stopped serving food every time he rang the bell, he found that the learning curve for the lack of relationship between cue and food was also individual for each dog.

The lesson is that we must constantly maintain a cue or cue if we want the horse to maintain a connection between that cue and a particular behavior. During training, the following training sequence should exist:

1. First, we SHOW the horse a corridor of controls that helps him understand what shape, direction, etc. we want to get from it.

2. We then use this hallway to ASK the horse if he understands what we want him to do.

3. Once the horse starts to understand, we can use this hallway to TELL him what to do.

At the last point in the training sequence, the horse will respond to the corridor of controls as if it were a signal. And here comes the misunderstanding about the use of controls and signals/prompts. When a horse does not respond to your request, the first thing you start to resort to is coercion. However, you cannot force the true signal, Pavlov’s bell. And real coercion does not mean punishment.

If cue/cue is an association the horse has made between a particular corridor of controls and the behavior you want from it, you can remind the horse what that association means by going back to the first two steps of the training sequence and support the horse. As you return to the corridor of controls that the horse understands to reinforce what you told him to do, you can increase those pressures methodically without creating any hiccups. You cannot force behavior with a signal.

When the line between a control and a signal blurs, remember that you want to do more than just turn a switch on/off. You want the horse to understand, you want to be able to change actions the way you change every part of any corridor of controls. The truth is that you must be fully aware of whatever you are doing. You must pay attention to what you are doing and how the horse reacts to what you are doing. Then you analyze the situation from the horse’s point of view, change your pressure corridor and show, ask or tell the horse again. With each repetition, you improve your relationship.

Ron Meredith. Translation by Valeria Smirnova based on site materials http://www.meredithmanor.edu.