Point of View: Reflections on the Essence of Rider Independent Balance

Point of View: Reflections on the Essence of Rider Independent Balance

The brown leather riding chaps I wear are over seventy-five years old. Their carefully oiled skin was finely dressed and belonged to my uncle before me. I have owned them for forty-five years. I am the only one who cares for chaps, cleans, stores. This is a modest but priceless treasure that reminds me of where I came from over 30 years ago, how I learned to sit in the saddle, train and train, work horses, understand them, about the method that was born with me and which I still use it today in one form or another.

Spain has a rich and ancient tradition of working equitation: classical and country dressage, used to control herds of sheep and cattle.

The first lesson I learned was about rider balance.

We have been raising sheep and cattle on our farm for many years. Many times I accompanied my uncle on three and four day trips to the country markets where we sold our livestock. We slept like cowboys out in the open, using saddles for pillows and our serape for blankets. approx. transl.). We pastured our sheep and cows on horseback. The area was not deserted, trees grew everywhere. Through this activity, I learned to anticipate the actions of animals and keep the herd together, moving at full speed or tackling through trees, sometimes jumping over small streams. I had to show a remarkable reaction in order to return a lost sheep or a too independent cow to the herd.

By learning to instinctively move smoothly with the horse, I could catch up, turn around, or drive a sheep or a cow away from the herd. Shifting forward to speed up, shifting to the side to avoid branches, shifting back to sit more firmly… I didn’t even think about my actions as a manifestation of working equitation, but I learned to be “alive” on a horse. I tried to position my body in such a way that its position helped the horse, I sat balanced, not pulling on the reins, not pinching the sides of the horse with my legs, not pushing with my seat in the back, not jerking the reins, no matter what happened. I moved with the horse and helped him do the job he was asked to do well, as efficiently as possible.

We were poor, my family used horses only for work, and it was unacceptable for us to bring a mother, a gifted cavalry, a lame or exhausted horse.

I never saw the point in having a rider sit tight on a horse, his elbows would be “glued” to his sides, his legs and arms would be fixed. How can a horse be required to match the balance of the rider, when the rider himself may be 15-20% of his weight, and it is he, the horse, who performs the bоmost of the work.

And today I continue to ride with independent balance and adapt to the horse under me as he learns to carry himself with me on his back. As he learns to move forward and sideways, to do changes, pirouettes and more, I try to help the horse by shifting my weight, sometimes exaggeratedly, to where it can help him the most.

We strive to create a strong, flexible horse and this means that he can carry himself and the rider is free to use his body and arms as he needs, performing different figures, whether with a garrocha pole (a garrocha pole is a pole 10-12 feet long with a loop at the end.They were used by the Spanish vaketo instead of a lasso. approx. translation.).

As my horse gets better and better at what I’m asking him to do and he has enough strength to do the job confidently, I return to a more traditional position, although my seat is still alive.

Working with young horses, I have learned to compromise, not to expect too much. If I ask to stop, I’m happy that the process can take several steps for the horse to stop his momentum while maintaining his balance. As she becomes more balanced, she will be able to stop faster without taking so many extra steps, until finally she can stop immediately when I ask. A young and inexperienced horse needs time to figure out a new balance, and the more we help him, the faster he will succeed.

With a working equitation horse, it will always be paramount to provide assistance, and this rule must be maintained for any horse and any discipline. At fourteen I went to work for the Domecq family, who had an estate in Andalusia. There I learned Rejoneo (Horse bullfighting), Doma a la Vaquera (traditional Spanish riding style, traditional dressage) and Acoso y derribo (traditional sports game Doma a la Vaqueraa) along with Álvaro Domecq Romero. Soon enough I began to train horses for Doma a la Vaquera and Rejoneo, working three or four horses daily.

This style of work required the horse to be able to traverse, shoulder in, half, single or multiple pirouettes, air changes, piaffe, passage and Spanish walk. Although all these movements are present in dressage, there are three differences: 1) since we hold the pole of the garrocha, the reins are taken apart in one hand, and not in two; 2) this work can be done at a higher speed than in dressage; 3) the repetition of movements and the pattern configurations we make are different.

For example, when working with cattle, bulls, rider and horse, you may have to do a series of three or four tight pirouettes, move at speed into a half pass to the right, then to the left, make a change in the air and immediately after that go into a series of pirouettes in another direction.

In comparison, in dressage, these same movements will be performed as if in slow motion.

This is the second and most important lesson I have learned from my work. The more balanced and better able to carry itself at high speed or to move in place, the working equitation horse, the better he knows that the rider is not blocking him, but, on the contrary, helping him in his work, and the more the horse begins to trust his rider. In addition to making horses physically fit, flexible and athletic, this job taught me that there is a delicate connection between trust and balance. This is a lesson that applies to all horses, not just working equitation horses.

One of the most satisfying things I have found in working equitation horses is that there is really teamwork involved. There is quite a lot of talk about harmony and partnership in dressage, but I rarely see a horse that has a choice of how and what to do.

If you don’t listen to the working equitation horse when you need to separate the bull from the herd or herd the cows together in the corral, you can die. Not only does a working equitation horse need to be in independent balance to react and move as fast as lightning without being blocked or slowed down by the rider (who cannot process information as fast as a horse would when looking at a cow), but it must also know that the rider believes in her and knows she can do her job.

You train the horse, you make him physically fit and balanced, you bring him into work gradually and safely, and when he is ready and when he takes over, you must say: “I trust you. I will guide you, but also listen to your opinion, and sometimes we will do as you see fit. Because you are a professional. Because you carry me. Because you do the brunt of the work and you know how the ground feels under your feet and what this cow thinks of us today.». You say “I’m your rider, but sometimes you’re the one who knows best” and that’s actually true with all horses…

A good rider must know the difference between his horse’s working instinct and disobedience, whether he is riding a dressage horse, jumping or working with a garroche, etc.

Like many working equitation riders who have ridden horses before me, I realized that if we ask our horse to believe us, then in return we must begin to trust him, the horse must earn our trust, and we must also earn the trust of the horse. . In truth, riding can be reduced to this: if rider and horse have independent balance, they will be confident in their ability to move together. If the rider prioritizes helping his horse, the horse will begin to trust him in return and gain even more confidence in him.

As the horse’s balance and confidence increase, so will the quality of his work, and as a result, the rider’s level of confidence in the horse will increase. When these conditions are met, there are few restrictions on what can be learned and achieved.

These lessons come naturally to us when we learn to ride in the fields and we have our own work to do. When our horse is our only companion, sometimes for a whole day, and our livelihood and sometimes survival depend on his confidence and well-being, we learn to appreciate his generosity. This is the best lesson of all – to know how to make a horse the way it needs to be, giving it a chance to be the way it is.

“I trust you. I will guide you, but also listen to your opinion.”

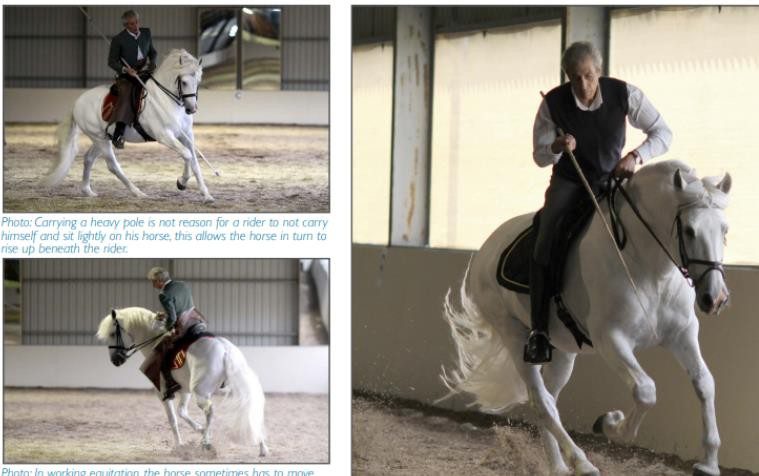

The fact that the rider has a heavy pole in his hands is not a reason not to support himself and sit quietly on the horse, allowing it to rise under the rider.

In working equitation, the horse often has to move at high speed and make very sharp turns or rotate several times in a row. The horse is responsible for his balance, and the rider for his. The rider shifts in the direction of travel, lightening the seat to free the horse’s back and help him achieve collection and make the best possible turn.

And sometimes it’s just a time to have fun and let the horse have its say. Dynamico loves this unloading at the canter, and Manolo gives him this opportunity.

Manolo Mendez with Caroline Larruil (source); translation Valeria Smirnova.