Our Relationship with Horses – The Meaning of Attachment Theory

Our Relationship with Horses – The Meaning of Attachment Theory

I’m interested in Attachment Theory as it relates to the connection between man and horse. I hope it can shed some light on the elusive, illusory issues of trust, rapport, and connection. I am convinced that Attachment Theory can be applied to horse training because the horse is a social animal.

Recently, this theory has been expanded – not only the relationship between mother and baby, between educators and pupils, but also relations between adults and the relationship between man and domestic animals have been described. There is much evidence that dogs and people bond to each other in the same way that humans bond to each other, and I think that probably any social animal that is within our environment is capable of sharing the corresponding feelings in at least some , albeit minor aspects.

We’re talking about horses now. The horse is the most fearful domestic animal. Her brain has the largest amygdala (the part of the brain that modulates fear) of any pet. In this case, the horse’s heart rate drops significantly when another horse pays attention to him by scratching the base of his neck. The same decrease in heart rate has been found to occur when people scratch a horse at the withers at the base of the neck. Research has shown that stroking, oxytocin, and lowering your heart rate are linked. In fact, it turns out that stroking the withers becomes an antidote to stress.

A horse that has the opportunity to participate in mutual grooming with other horses has better health indicators. Thus, horses kept in groups show significantly lower levels of stereotype scores (stress-related problems such as biting, pitching, etc.). This tells us that affection (in some of its manifestations) is a really important indicator, since it protects the horse from fears and feelings of being in danger. And here we are faced with those scientifically inexplicable factors that can speed up (improve) or slow down learning: trust and mutual understanding.

Attachment is the first thing I look for in horses because Attachment Theory, as presented by psychologists, provides us with valuable tools for evaluating and correcting behavior. It is of particular interest to me because the training of the horse usually does not affect him at all. We lead the horse, we guide it during the ride, we work on the lunge or in a round barrel – we are always at a distance. Even when we ride a horse, there are layers between us. Where is that tactile attachment, the importance of which is so important for close relationships? Touch is soothing. The need for touch is a stream in which the water evaporates quickly, and therefore, unlike other primary needs, it can never be fully satisfied.

Touch is really important. But are you sure that you regularly touch the horse for some reason other than to clean it? People often pat the horse, but the pats, at worst, cause the horses to become sharper, more alert, and more alert. At best, this becomes a neutral signal that does not improve learning at all. But we can’t stop patting horses, dogs and elephants. And this is a waste of time and emotions. As a result, animals become accustomed to our actions, but if we did not pat the horse at the base of the withers in response to good behavior, but simply stroked the horse at the base of the withers and pronounced “good boy” clearly, using the voice as a secondary reinforcement before stroking, we would achieve more. success. Especially if we acted like this all the time.

One French researcher tried to prove that withers strokes are not effective reinforcers. In his seminar, he rubbed the horse at the withers three times, and the horse showed no decrease in heart rate. However, it is a fact that in some horses this does not change for two minutes in the early stages, probably for the same reasons that are present in single children who sometimes resist contact. Social animals need touch, but don’t always show they want it, especially if they haven’t experienced contact often.

For me, in working with horses, the importance of touch is undeniable. They mean much more than mere reinforcements. It is about the safety of an animal that can live in a world without touch, but craves it, being a social animal. I believe that the genius of Kell Jeffery’s revolutionary dressage method, which has been used by me and other riders (eg Parelli) lies in the habituation effect between rider and horse during bareback contact. The rider spends a lot of time lying on the horse’s back, stroking its sides, soothing with touches. Attachment is an absolute rarity at such early stages of dressage …

We must use touch, especially stroking the withers, both in pony clubs and in stables with top-level horses. This is a wonderful reward for a horse.

What else can be a reward for your horse from his point of view? Social contact through touch is natural, and I have observed many horses who initially did not like to accept scratches from other horses (most likely because people are so inclined to isolate horses from each other), but when placed in groups, they soon learned to enjoy from touching and scratching their comrades in the herd. Horses that seem to initially dislike human touch can learn to enjoy it – you just need to persevere. And this is important for their health – tactile contact relaxes the horse.

There are other reasons that make me think about Attachment Theory. I read a book about Harry Harlow’s famous experiments with rhesus monkeys, which demonstrated what we already knew from research on child behavior – if a monkey baby was deprived of the touch of a caregiver, he would lose vitality after a few months and did not develop physically, did not start communicate (“talk”), and after longer periods of time, recovery became impossible and many monkeys died. Another interesting point is that new research on synchronization between humans and horses has shown that when there is good partnership between rider and horse, heart rate tends to be synchronized. Linda Keeling in Sweden has done some fascinating experiments (which we are about to repeat). They showed that when a person leading or riding a horse begins to expect something bad, the heart rate increases in synchronism in both. Perhaps it is as simple as when the rider’s tension is transferred to the horse. Perhaps it is worth saying that we cultivate certain interesting traits in horses, just as we do in dogs, which we do not yet fully understand.

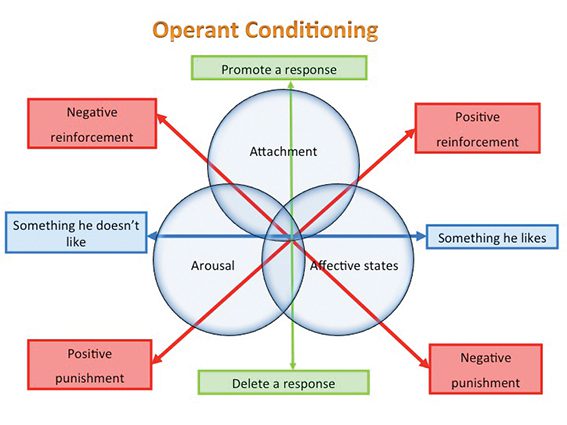

In my opinion, doing the right training along with using the right tools of Operant Conditioning, and taking into account the horse’s arousal, affective states, and attachment needs, can lead us to perfect training.

Operant conditioning (top to bottom, left to right): Contribute to the answer -> delete the answer; Negative reinforcement -> negative punishment; Something the horse doesn’t like –> something he likes; Positive punishment -> negative punishment. Circles: Attachment. Excitation. affective states.

I think we need to be honest about training. We must recognize that when the aids we use in training a horse are pressure relief, then even the most subtle cues are still a shortened version of negative reinforcement. If we do it poorly, it harms the horse and leads to problems.

We should not abandon negative reinforcement in favor of positive reinforcement – this would mean a poor understanding of the processes of cognitive training and a denial of the fact that a horse is a dangerous animal if you do not have control over it. Control over the centuries has been conditional onnegative reinforcement and allowed the rider to control the horse in the horror of battle. In a calm environment, this can create a calm, confident horse that you can rely on for safety – you won’t be afraid for your child if he gets into a difficult situation while on a well-trained horse. Therefore, it is important for me not to deny negative reinforcement, but to accept it and always remember that we must do everything to the best of our ability – reduce pressure to the lightest signals and reward the horse with a touch.

To truly build relationships with horses, we must replace the familiar simplistic notions of respect, dominance, and submission and use Learning Theory properly. The more you know about it, the more it explains how your mind thinks about submission and respect. Even when a horse invades your space, it simply means that it has learned to push you out through negative reinforcement. When she “displaces” you in the saddle, she does the same. When the horse does not want to be loaded into the horse carrier, it is a refusal to accept the leading pressure provoked by negative reinforcement. When a horse behaves aggressively, when it is lazy, does not obey, hangs on its hands, the same thing happens.

I know that some people hate science because they are not able to systematize knowledge, to look at the world in a complex way in all its versatility. We understand the world as long as we look with open eyes at all that is important and are not afraid to open ourselves to our own arrogance. I have always wondered how people who do not trust the veracity of the scientific approach can skydive. But when it comes to animals, sometimes what seems gentle and kind to us (i.e., being allowed to accidentally push or move you on the ground or under the saddle) is not good, because all this makes horses unsafe. This is where Learning Theory comes to the rescue.

But even without a deep understanding of learning processes, we need to remember that our job is simply to teach the horse what we want, and as effectively and thoroughly as we can, which will make him as safe as possible.

Andrew McLean (a source); translation Valeria Smirnova.