Men and women: who is better suited for riding?

Men and women: who is better suited for riding?

This article (in its original version) was first published in Equus Magazine in 1989. The subject to which it was devoted – the manifestation of differences in the structure of the male and female skeleton in riding, was discussed for the first time. This topic was very rarely raised in articles devoted to horses and riding. The response was overwhelming: the article won a national magazine publishing award, and many seminars, books, video tutorials, and the like followed shortly thereafter. (not my authorship) about “women in the saddle.” And today, after so many years, I still hear talk about the difference between male and female anatomy and how it affects riding, mostly from people who never mention my name, not knowing that the information presented here reflects the original research.

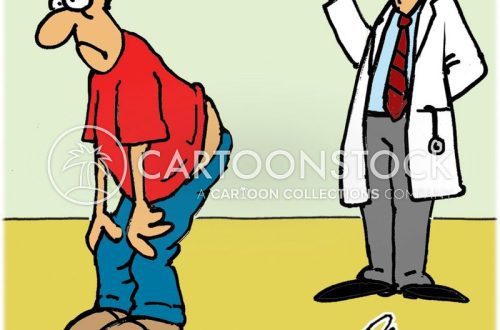

I had two incentives to investigate this issue and publish relevant information. A bad stimulus was the sheer amount of instruction I received during my equestrian life from my dressage trainers who insisted that I trot with my belly forward, stretching my loin joints excessively and arching my back. Perhaps this sounds familiar to you too … I developed pains that eventually became excruciating. Once I realized that if I sit on horseback again, I will get an intervertebral hernia. Soon my intuition was confirmed by my attending physician.

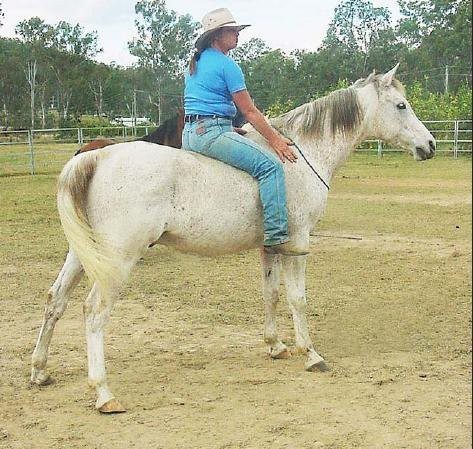

My classes with Sally Swift became a good incentive. I attended two workshops she taught and was taught to let go of the lower back muscles, allowing her to straighten as far as my bones would allow. And, my dear readers, you will soon see how exactly they allow it, because drawings No. 5, 11 and 14 are my photographs. My body structure is quite typical for middle-aged European women. I was 34 when the black and white photographs were taken; color photographs show me after 40. I say this so that later on you can compare your build and your experience with mine.

Who is better suited for riding

The history of horsemanship is almost entirely the history of men on horseback. And this is not the lamentations of a feminist – it’s all about the war, the conquest of new territories, the migration of people and the history of the science and art of horse training, as such. Profound changes took place in this area after the Second World War. In developed countries, horses have ceased to be a necessary component of war, agriculture, or even transport. And today, women, not men, make up the vast majority of riders.

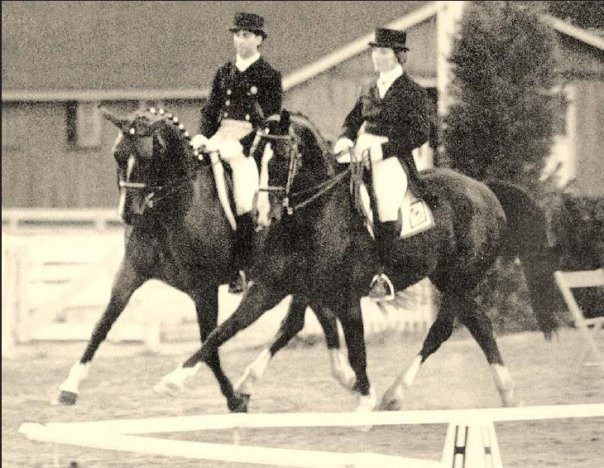

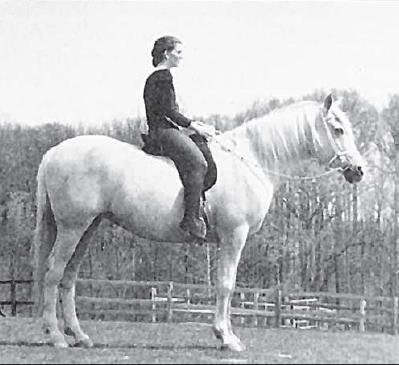

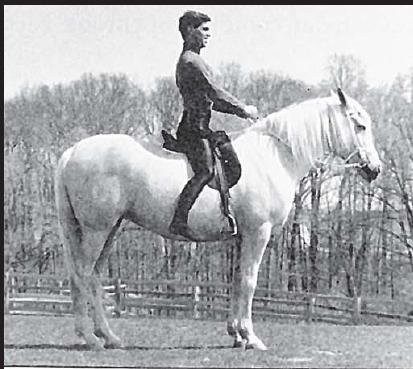

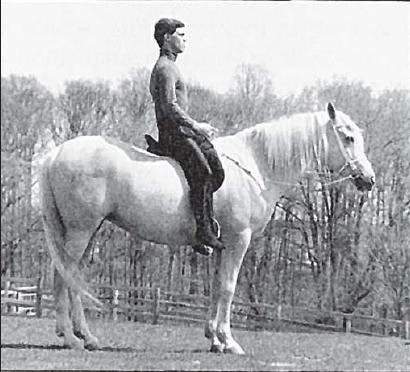

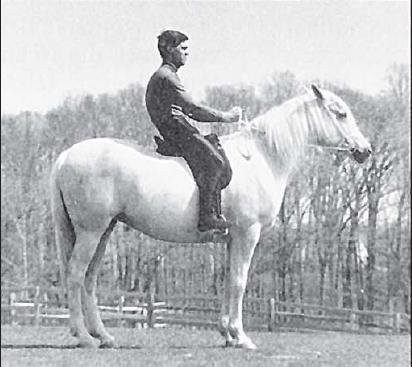

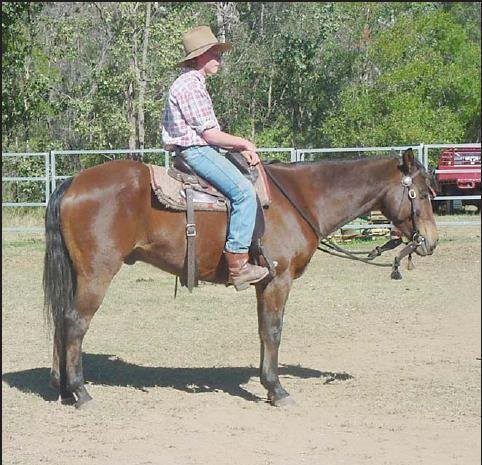

Rice. 1. Both riders, excellently mounted (Robert Dover and Kay Meredith), show typically masculine and typically feminine adaptations to the problem of sitting at a powerful trot. Before the Second World War, the majority of riders were men, but today women have taken their place. Since women have a markedly different bone structure from men, the methods women use to “follow the horse’s movements” must be different from those used by men. Instructors of both genders must understand this fact and modify their instructions depending on which gender they are dealing with.

Now both men and women ride the same way, in boots and breeches like nineteenth-century pageboys, tailor-made suits like 1920s society ladies, or jeans and fringed chaps like cowboys. Ladies riding is rarely shown even in show programs, and magnificent processions, when women went hunting or walking, sitting sideways behind their man, are a thing of the past.

However, despite women’s rejection of masculine theories of good manners, it is worth seriously considering the ways in which saddles somehow adapted to the characteristics of the female physique. The greatest horse cultures, including the Comanches, Sioux and Crows, who lived in the XNUMXth century. in the Great Plains of North America, they traditionally made different types of saddles for men and women. Their different appearance reflected not only their intended social roles or work responsibilities, but also the corresponding differences in body structure.

Structural differences

Rice. 2. The fashion for posture, in which it was necessary to stretch (bend) the lower back excessively, protruding the stomach forward, and strongly unbend the knee joints, went back to the book by Pierre Ramus “The Dance Teacher”. It was intended for the education of wealthy people who needed to shine at court and in good society. What this actually led to, and continues to do to this day, is physical injury not only to riders, but to figure skaters, gymnasts, speed skaters, and ballet dancers.

In the musical My Fair Lady, Professor Higgins rhetorically asks, “Why can’t a woman be more like a man?” In the art of horsemanship, this question becomes practical: a woman cannot ride like a man because her lower back, pelvis, and hips, those parts of the body whose functioning is so important for successful riding, are constructed differently from those of men. This doesn’t mean women can’t drive like men; it’s just that these anatomical differences suggest a difference in the performance of tasks, such as half-halts, for example, and in the landing at the training trot, for women and for men. They also mean that women will have different difficulties in learning to ride than men, and then, at a more advanced level, different burdens and benefits.

Riding instructions, especially systems designed for dressage and eventing, which simulated military situations, were originally created for men and tested by them. Riding methods that are suitable for men do not work as well for women, and some may even be harmful. The first step in developing rational and effective methods for teaching women to ride is to make sure that both riders and their instructors are aware of the difference between male and female anatomy, and understand exactly how important parts of the body of both sexes function in the saddle, such as acetabulum, lower back and ischial bones.

Pelvis

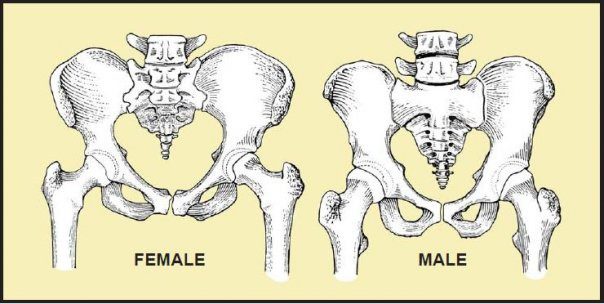

Rice. 3. Front view of the female (left) and male (right) pelvis. The female sacrum (coccyx) is directed strictly backward and narrows more towards the lower end than the male. The male sacrum covers the birth canal (central empty area) much more than the female. Notice how closer the acetabulum is in men than in women.

The bipedal locomotion inherent in our species is unique. Over time, the shape of the human pelvis has changed from the elongated and narrow, characteristic of dogs, horses and gorillas, to the wide, flattened, bowl-like shape adapted to attach our legs and provide a solid foundation for our insides. Our species has significant physical differences between males and females, and the most notable of these is in the pelvic region.

The design of the pelvis in men and women is different, because women give birth to children whose heads are huge compared to other species. The female birth canal is closed and limited in size by a bony ring that forms the pelvis. As a result of the biological need to ensure successful childbearing, the female pelvis is almost everywhere wider and deeper, with a more round pelvic outlet than the male.

From a riding point of view, it may seem that women have an advantage here: the greater width of the pelvis should make the task of sitting on a wide horse less difficult. Moreover, the proportionately large size of the female pelvis has the effect of lowering the center of gravity when mounted on a horse’s back, thus making riding more stable and more difficult to fall out of the saddle compared to men. But, unfortunately, in military systems of riding training, especially those that require the rider to “follow the movements of the horse at the training trot and canter,” these advantages fade away. The rider is not like a bowling pin that was placed on a horse – in addition to the “bottom” he has a torso and legs, and neither the female waist nor her legs connect to the pelvis in the way that men do. As part of the pelvic structure as such, the sit bones in women are also shaped in a special way.

Ischial bones

The rounded sit bones form the lower part of the human pelvis, and it doesn’t matter if you’re sitting at a gaucho trot or dressage, sit on your sit bones. These structural parts have long been the subject of controversy in every equestrian school. What is known for certain is that the sitting bones are shaped differently in men and women, and this difference leads to different riding habits in each of the sexes.

One of these “skills” is stoop. Obviously, slouching (on the horse’s back or elsewhere) creates poor posture. Because of the shape of the sitting bones, when a man stoops, he rounds his lower back and sits on his tailbone (a classic example of cavalry stoop). Men who compete in amateur western, polo and reining also often sit “on their pockets”. This position is rarely seen in women, as rounding the lower back is anatomically difficult to achieve for most women.

One of the key ideas of dressage instructors has long been to eliminate stoop by teaching riders to arch their lower back. For many centuries it was believed that aristocratic men and women should have a posture that is based on excessive stretching of the lower back, which prevents stooping due to the forced tension of the back muscles throughout life.

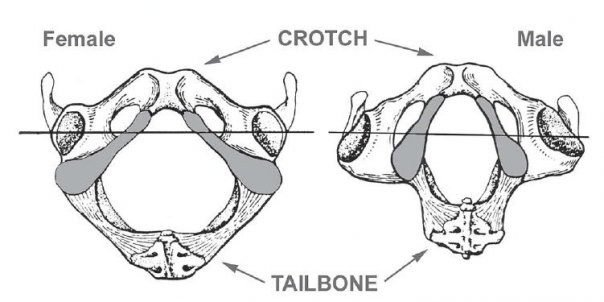

Rice. 4. The pelvis, as it “looks” from the saddle (left – female, right – male). Note how widely the ischial bones (marked in dark gray in the figure) diverge in women, while in men they are almost parallel. In men, the acetabulum is directed forward, while in women it is more to the side. The axis of the female pelvis lies closer to the front of the ischial bones, and in men it divides them into two balanced halves. That is why the female pelvis “wants” to balance forward, and women have to make an effort to lower the coccyx. And men, on the contrary, can easily sit “on their pockets.”

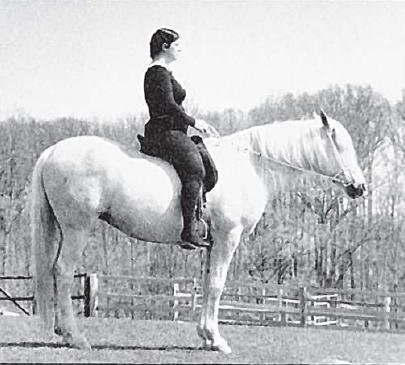

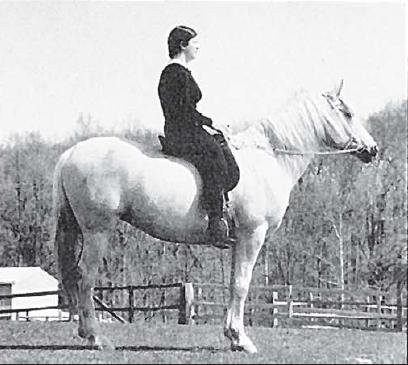

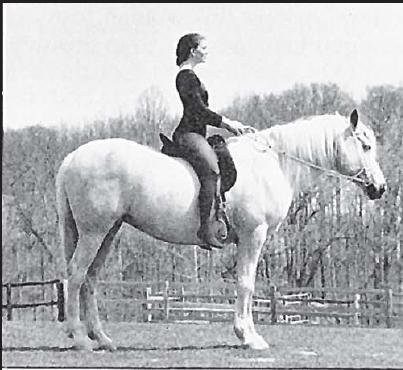

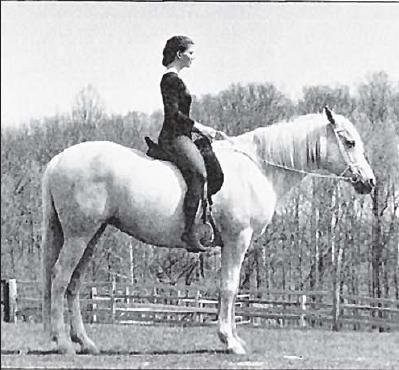

Figures 5-7 allow three different riders to be compared with each other in three different postures on the same horse.

The three riders are me at 34, my slender assistant Jennifer, 22, and tall, athletic Jim, 24.

The top shots of each of us reflect a position with an overstretched (bent) lower back and a correspondingly lowered groin.

In each middle shot, there is a “normal” position, in which there is neither excessive stretching nor relaxation. The rider sits directly on the sitting bones.

In the lower photos – a relaxed position with a rounded lower back. The riders try, as far as possible, to “sit on the pockets of their trousers.”

Compare the X-rays of the male and female pelvis and lower back in Figures 8 and 9. It will be physically impossible for me, as for other women, to make the lower back as flat as the average man.

Jennifer riding Sadie.

Pay attention to the first photo (excessive stretching (deflection) of the back). Smell with such a landing goes down, because of which the rider rounds the curve of the thoracic spine, sticking out her chin. Lowering the groin reduces the angle between the pelvis and thighs.

The middle photo shows a “normal” fit directly on the sitting bones. All curves of the spine are less pronounced; the angle between the pelvis and thighs is wider.

The rounded lower back (third photo) shows us the maximum possible fit “on the pockets of the trousers.” As a rule, in women, such an effort results in a greater rounding of the upper back and shoulders than the lower back. Some riders may also feel the need to spread their elbows out to the sides or raise their knees as well (“chair seat”). Some knee lift is a compromise for many women, because if they don’t lift their knees, they won’t be able to properly relax and straighten their lower back.

Jim riding Sadie.

In the first photo we see excessive stretching. Compare the amount of lumbar arch that Jim can achieve with what we observed with me and Jennifer, it is much more difficult for Jim to achieve camber, but with effort he can do it. Overextension of the lower back is the basis of the “military” position, as in men it forces the chest and shoulders to rise, making them look taller and more impressive. Notice how the drop in Jim’s groin causes his hips to lean back, much further than in the same situation in women.

Let’s move on to the “normal” landing directly on the sitting bones. Notice Jim’s completely flat lower back and slight backward tilt of Jim’s body. Some static is felt, a common feature of muscle strength. When the lower back is bent, both in women and in men, the “yielding” should be backwards rather than forwards.

The third photo shows how Jim rounded his lower back as much as he could. This is clearly much more than what women can do. Note that the point of greatest curvature of the spine is below the line of the chest. The loin stays perfectly straight, but the entire pelvis has rotated thirty degrees to put all of Jim’s weight on his pockets and lifted his groin quite a bit. There is also a tendency to raise the knees.

Fashion dictated extremes in this position of the body during the 18th and 19th centuries (see Fig. 2). And today we continue to be influenced by the standards of academic riding.

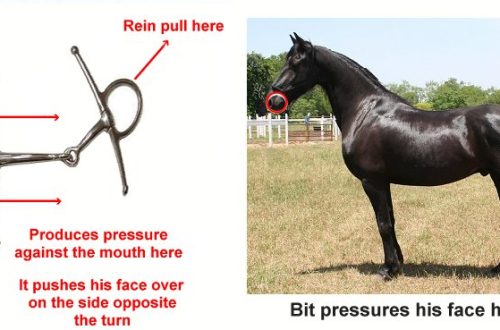

The contours that the sit bones form in the saddle dictate their functional properties. The male near-parallel sitting bones function like the parallel wheels of a toy trailer: they allow the pelvis to roll freely back and forth. In women, the ischial bones, on the contrary, strongly deviate back. Like the wheels of a trailer set at an angle, they resist rolling, especially backwards.

The horizontal axis of the male pelvis from one acetabulum to the other also aids in rolling back on the sit bones onto the coccyx, as the axis passes over the center point of the sit bones. And the horizontal axis of the female pelvis passes over the ischial bones closer to the front edge. Also, because of this circumstance, the female pelvis “wants” to balance itself more forward, lowering the pubic bone and lifting the coccyx, in contrast to the male. A woman has to make an effort to lower her coccyx, while a man has to make an effort to lower his pubic bone.

This anatomical fact explains why men and women don’t usually “stoop” in the same way. When a woman stoops, her stoop is usually not, provokes lowering, but raises the shoulder blades. Of paramount importance is the correct diagnosis by the instructor of the underlying causes of slouching in students, whether male or female (there is a slight exception: some men have wide and divergent sit bones; as well as some women, they are narrow and parallel).

The traditional fix for a stooping cavalry recruit was to train him to “push” or “throw” his belly forward. This command forced the rider to apply the physical force necessary to lower his pubic bone. After that, he would sit on his sitting bones, keeping the pubic bone closer to or even on the front pommel. This is called “sitting on three points”. This positioning has been found to be more comfortable and beneficial for men, and is not painful for most men who practice it.

However, an instructor who errs in identifying the anatomical causes of bad posture in his students by requiring them to also lower their pubic bones exposes them to physical danger. As the x-ray of one woman shows, stooping due to the rounding of the lower back is basically impossible for her. When she slouches, her shoulders are rounded, but her lower back is always arched. If this woman is asked to press the pubic bone against the saddle or to throw the already arched lower back further forward, this will lead to overstretching of the junction of the vertebrae that form the lower back and its transition to the sacrum. This, in turn, pinches the intervertebral discs and causes the articular surfaces between the lumbar vertebrae to overlap each other. As soon as her horse takes a sharp step when her back is in this position, a woman having such a structure will be in danger of displacement of the vertebrae, the occurrence of a herniated disc, or even fracture of the bones. Given the misdiagnosis and anatomically inappropriate instructions, it is not surprising that many female riders now complain of chronic back pain.

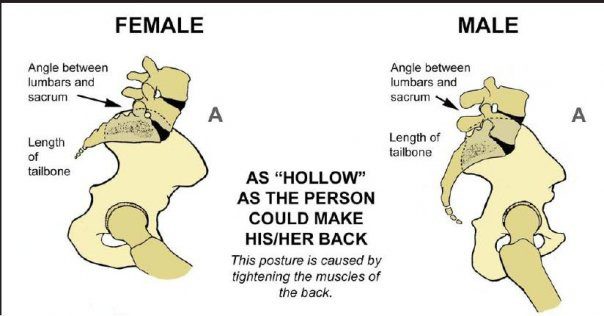

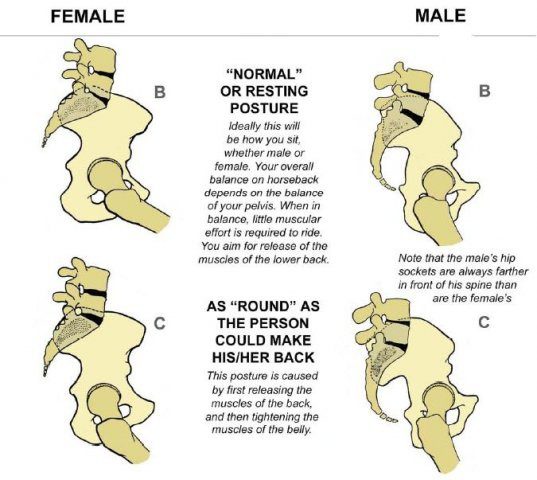

On the left we see the female pelvis, on the right – the male.

Signatures on the left in front of the arrows:

The angle between the loin and the sacrum.

Tailbone length.

The inscription in the middle: the most “bent” back position that a person can achieve. This position is obtained by tension of the muscles of the back.

Normal or relaxed position.

This fit is perfect. Your overall horseback balance depends on the balance of your pelvis. A balanced position requires little effort for riding. You need to relax your lower back muscles.

The back is rounded as much as possible.

This position is created, firstly, due to the relaxation of the muscles of the lower back, and, secondly, due to the tension of the abdominal muscles.

Small of the back

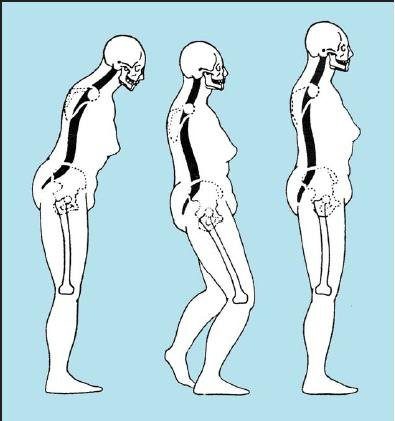

Rice. 9. Body positions that women adopt in order to lift the groin, straighten and relax the lower back.

LEFT: Bend forward at the waist. This straightens the lower curve of the spine, but after a few minutes the muscles of the lower back will feel tense, because when the body is in such an unbalanced position, they must all the time support the weight of the upper torso and head.

MIDDLE: Bend your knees and lift them up. This is the method that provides the most lasting comfort and ease. In the saddle, the rider achieves this by simply not trying to stretch her legs down and back past the point where the hips begin to drag the crotch back.

RIGHT: Apply force to straighten the curves of the back with the help of deep internal muscles (mainly the iliopsoas complex, which lies opposite the anterior edge of the lumbar curve). Exercise systems such as Pilates and yoga safely strengthen the muscles that support posture and are very good, as are vaulting exercises. When you are in the saddle, you should not be training. Ride with balance and feel for the horse, no matter how strong your muscles are, you will already be supporting yourself while riding.

While your mother may have been trying to fix your stooped teenage back by slapping you between your shoulder blades, this, like the idea of the Spanish Riding School’s riders training with the board under the jacket, is just a misconception about how to fix the posture. In both men and women, a comfortable body position is formed by a series of vertebrae conveniently located in length above the pelvis and sacrum. Good riding is impossible without good posture. In order to “follow the horse’s movements”, the rider’s loin must be able to elastically perform a full range of motion from a stretched (bent) through a flat to a slightly bent (rounded) position.

As with the pelvis, the shape of the lower back in men and women is not the same. Differences in this area of the body begin in a peculiar triangular bone called the sacrum. Anatomically, the sacrum works like a bridge – it is an angled stone that connects the lower back to the pelvis and legs. In representatives of different sexes, it is formed and combined with the pelvis in completely different ways. Because the lumbar spine sits on top of the sacrum, differences in the shape of the sacrum and its location require differences in the structure of the entire lower back.

In most men, the sacrum is elongated and curved. Thus, the bone enters the birth canal area, but in men this does not matter. Because of this shape of the sacrum, it becomes possible for the average man to sit on his coccyx, something that will never be possible for the woman whose x-ray accompanies this article.

For riders and riding instructors, the anatomical differences between the loin and sacrum are even more important than the differences between the pelvis and hips, because the female sacrum is so inclined that her lower back curves more than that of men. In addition, when a woman sits at ease in the saddle, her acetabulum lies under or even behind the lumbar spine. If gravity were allowed to act on a woman’s pelvis, it would roll forward and her lower back would sag more. As for men, their acetabulum is in front of the lumbar spine, and if a seated man relaxes his back muscles, his pelvis will roll back; gravity will pull his coccyx down and as the sacrum descends, his pubic bone will rise.

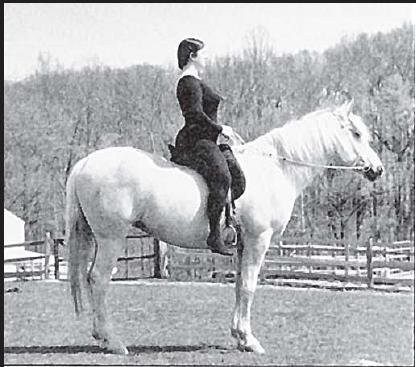

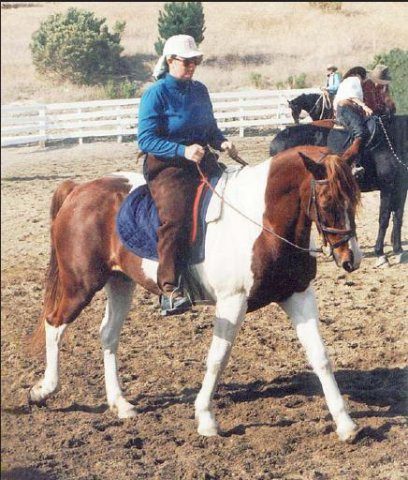

Here I am riding in a relaxed way. We perform lateral movements in a slow, relaxed, collected canter. My horse is completely satisfied with this, as can be seen from the wide “V” that his ears form. He also puts in his best effort, as evidenced by the concentrated look in his eyes and the long, “stretched” lip, the horse’s way of saying, “I’m doing the best I can.” This photo was taken when I was 46. Believe it or not, I didn’t try to put my heels down – they went down on their own because my entire lower body, from the waist down, is relaxed. This picture shows how much Sally Swift’s methods have helped me. I no longer have difficulty relaxing my lower back and “following the horse’s movements”.

Why do women tell me so often that they like to ride bareback? Very few saddles on the market today are actually designed to fit the female anatomy or help her solve the problem of frontal crotch drop. But horses without saddles have a completely different shape – most of them have the center of the back below the withers. They have some kind of “notch” or groove where the rider’s legs naturally tend to be. And this groove is in front of, and not behind and below, the acetabulum of a woman. Both of these factors help to rotate her pelvis up in front, relieve overstretching of the acetabulum and lower back, and help the woman to relax and align her lower back.

This young woman is well “adapted” to “sitting on trouser pockets.” However, the “relaxed fit” in women and girls still looks completely different than in men (below) due to internal differences in the structure of the skeleton.

Acetabular cavities and femurs

The “seat” of the rider is formed not only by the contact of the sitting bones and surrounding soft tissues with the saddle, but also by the upper thighs. The ball-shaped head of the femur is inserted into the acetabulum of the pelvis, but the position of the acetabulum, the angle of the femoral neck and the angle of the femoral shaft have characteristic differences in men and women.

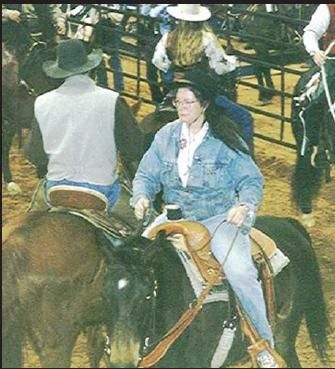

This is me in 2001 at age 49, participating as a guest rider at the Tom Dorrance Show at Fort Worth, Texas. This photo was taken from a stand that showed how women’s hips actually work: they are conical, regardless of whether the woman is overweight, normal weight or slim. This means that when a woman sits on her sitting bones, asking her to turn her toes inward, turning her shins or turning her hips inward, will deform her hip, knee, and calf joints needlessly. Such coercion does not provide functional benefits, does not improve safety, but simply puts the body in a certain position. Instead, the rider, whether male or female, should try to bring the inside of the lower leg into contact with the horse’s body. Once this contact has been made, it doesn’t matter where the toes point. The rider must be taught to use his sartorius muscles to keep the leg closer to the horse, or to push, hit or spur him when necessary, not the biceps on the back of the thighs, or the long adductors that lie on the inside of the upper thigh .

In most men, the acetabulum is turned forward more than in women. This makes it easier for them (even those who are obese and have full hips) to lay their inner thighs flat on the saddle surface, avoiding the awkward and strenuous pointing of the toes forward. In order for a woman of normal weight to meet this requirement, she needs to stretch the muscles on the front of the thigh and the iliofemoral ligament, which, when taut, limits the movement of the femoral head.

Another outstanding characteristic of the female femur is the angle at which it descends from the pelvis. This thing, called “trail angle,” is determined by the angle at which the femoral neck connects to the femoral shaft. Women tend to have hourglass-shaped thighs and calves as their thighbones slope inwards from the hips to the knees. During the march, the higher the parade participant raises her knees, the closer they approach the center line, while the knees of the participants usually still remain in place. The more a woman can open her hip joints by pulling her hips further back, the easier it will be for her to keep her knees further apart and her toes pointing forward instead of out to the side when she is in the saddle. Thus, the farther back a woman can bend over so that her knees are under her while riding, WITHOUT DOUBLE LOUS BACK, the better she will ride.

The lower end of the femur also reflects the angle of outreach. In general, in men, the hip joints form a hinged surface that is almost at right angles to the shaft, while in women, the joints are inclined. Since its articulations tilt, the female fibula is not suspended directly below the knees, but deviates towards the ankle joints. This in turn affects the position of the lower leg and foot. For women who have achieved a proper fit and want their position to be as effortless and relaxed as possible, with the legs hanging down naturally, tilted or double-angled stirrups compensate for the curves created by inside the female leg and are preferred.

If you are trying your best to sit better, then knowing the anatomical differences that distinguish men and women will help you greatly improve your riding. If you are a riding instructor, this data may force you to reconsider your approach to different students. The main goal is to enable every person, man or woman, to be able to “follow the movements” of the horse and influence it without making any effort.

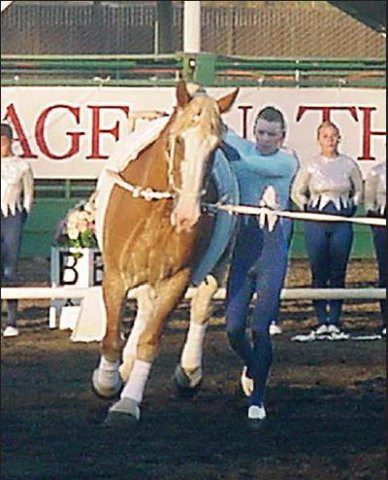

A couple of really great shots that show how differently the anatomy of men and women functions. The riding instructor can demonstrate mounting, in which he sits in the saddle, but does not wrap around it when he puts his foot in the stirrup – the saddles do not yet turn. This is possible because the male pelvis is so narrow that a male can place the center of his body closer to the center of a horse’s body than a woman can. These pictures show the same. Notice how much wider the female pelvis is than the male pelvis. Also pay attention to the “carriage angle” in women. Women’s hips from the pelvis converge down to the knees, while in men the hips are parallel. Also note how the location and loading of the woman’s feet differ. All anatomical features make female jumpers much more dependent on upper body strength, timeliness and ability to jump up than male jumpers, who may rely more on balance.

Deb Bunnet (source)

Translation by Nara Hakobyan (Dialogue with a horse / Dialoguewithahorse)