Manolo Mendez: thoughts on work in the hands

Manolo Mendez: mthoughts about work in hand

Hand work is an essential part of training a horse, whether it is experienced or not. This is how we prepare the horse for comfortable work under the saddle. Hand work allows us to first lay a good foundation and then help the horse move forward in daily training by strengthening the fundamentals, honing balance and rhythm, introducing and refining the movements.

I am convinced that work in the hands is the best way to get an idea of the horse’s intellectual and physical abilities, as well as to develop the most effective working relationship with him.

Traditionally, hand work is used to teach the horse the High School elements, piaffe and passage, but I have been doing hand work since the first day of training. This is how I teach a young horse how to use his body to become confident, strong, flexible and balanced. I help the horse build confidence and confidence, both in me and in himself, and at the same time I teach him balance and rhythm.

Good work in the hands requires from us the highest sensitivity – such that we may not be able to sit in the saddle. It requires physical fitness and a combination of body awareness, feeling and timing.

I’m talking about Body Awareness because we need the ability to move quickly and accurately in order to mirror the horse, to mirror what we’re trying to create in it. To help the horse bend, stop, move forward, etc., we must know how and where our body moves. We must be able to quickly and smoothly adjust our own position by observing the horse and how he responds to our requests.

I’m talking about Feeling because we need to relate the work to the horse’s biomechanics and to its previous experience, “history”, asking nothing more or less, knowing what is good for each particular horse, what should be the posture, rhythm, angles.

I’m talking about Timeliness because we need to know exactly when to influence the movement and posture of the horse in order for the work to be effective. It is also important to ask the horse to do something based not only on where his legs and body are, but also on where he is mentally.

Awareness, feeling and timing are also needed in order to determine if the horse has mastered the lesson and is ready to move on, or if he still needs time (maybe he needs to take a break or switch to another job).

We must use our feeling and awareness if the horse does not obey or understand us. I find that in most cases the horse is still really trying to understand the problem. If she does not do this, then often this is due to the fact that she is afraid, does not understand, or is asked from her that she is neither physically nor mentally ready to give. In such cases, we should not punish the horse. We must ask ourselves what we are doing that provokes the wrong answer, and how we can help the horse.

When we are teaching a horse something and putting together the pieces we have already learned like a jigsaw puzzle, we should not act harshly or violently. The cavesson can be uncomfortable if used incorrectly, and the work in the hands is designed to train the horse and build confidence and willingness to cooperate with the person. By forcing the horse, we destroy in him the desire to work with us, we destroy his confidence in himself and in us.

Hard hands, untimeliness, coercion or the use of punishment for no reason, whether in the hands or under the saddle, can destroy the horse’s rhythm and balance, creating problems that will need to be corrected. Hand work is a unique and very effective tool and must be used correctly and help the horse, otherwise it can be harmful.

Work in the hands should not be mechanical. We don’t run a horse around and wait for it to get tired. We do not repeat the same command over and over, regardless of whether the horse understands us or not. If we want to make it easier for the horse to learn and help him (first of all) develop straightness, rhythm, balance and confidence, and then proceed to learn lateral movements, eventually achieving the passage and piaffe, we must responsibly and seriously focus on , as we communicate with our horse.

We need to be able to observe and analyze the horse’s responses, and be willing to modify our requests so that the horse understands them better. By being calm, observant, and flexible, we will create the conditions for success, and not provoke the development of stress, which will lead to our own failure.

The success of hand work depends on several factors: how the horse was prepared before hand work began; conditionality, if any; and understanding what and how we are trying to communicate to them. We must work so that the horse does not become afraid and try to protect himself from us. She should listen and respond calmly.

The success of our work in the hands also depends heavily on our ability to pay close attention to the horse’s body, expression and movements, how he responds to our requests and signals.

I do not work in the hands with a bridle. Only with cavesson. I prefer the fully adjustable lightweight Spanish cavesson to the bulkier and heavier German and Austrian models. My cavesson has adjustable occipital, cheek and nose straps, a single ring (the impact is lighter than a cavesson with three rings) and a soft nose pad. It can be adjusted to the head of any horse, regardless of its size.

I am often asked why I recommend using a cavesson and not a bridle. My experience is that in insensitive or “beginner” hands, the snaffle can create a lot of problems with incorrect bending, making the horse fearful and resisting because of what is happening to his mouth.

In addition, I have found that the Spanish cavesson or “serrata” gives the coach bоmore flexibility in work, and the horse moves with bоmore enthusiasm and freedom than with a bridle. Because I want the horse to move freely and find his own independent balance without being “boxed in” or restrained by aids, a cavesson is the best choice for me. For the same reason, I never use side reins.

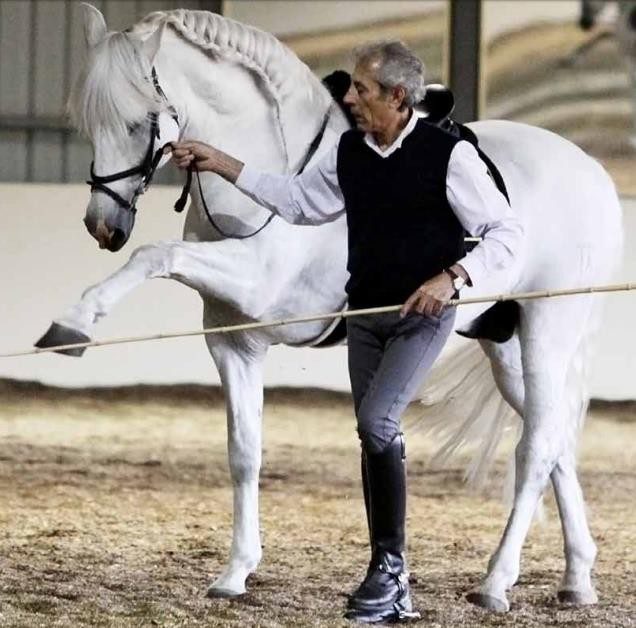

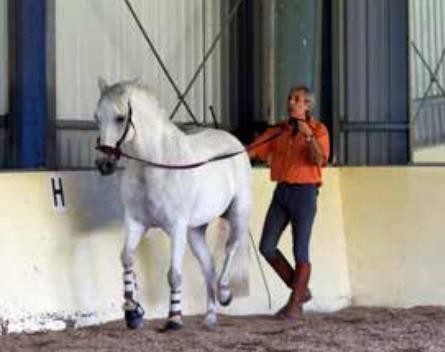

Hand work is a great way to prepare a horse for work under saddle. In the photo, Manolo is working on the Spanish step in his hands. He is very careful and makes sure that Dynamo moves forward when he lifts his front leg and does not lag behind.

2. Manolo has asked Joe to trot and is using the moment to observe the horse and decide on the next step. Without any pressure, he puts Joe on the circle, making sure that he is bending properly with his whole body. Correct bend – the natural bending of the body from the back of the head to the tail, coinciding with the arc of the circle. Manolo holds the cord in his right hand and guides the horse, he holds a bamboo stick in his left – it is directed at Joe’s hind legs, but is not currently sending out. The remaining length of the cord is safely coiled in Manolo’s left hand.

3. To encourage Joe to work his body better, Manolo lightly touches a bamboo stick just above the hock of the inside hind leg. With his right hand, he takes a little more contact and asks Joe to bend over a little more. At the same time, Manolo makes sure that he himself continues to move forward in the same direction as Joe, helping the horse maintain its natural forward rhythm.

4. Learning to work on three tracks of footprints. Asking for bending with his left hand resting on the cavesson, Manolo with his right hand, which contains a bamboo stick, asks Joe to bend and move in three tracks. Three-track work is a great way to pick up a horse without shortening its neck. This is the method that Manolo always uses, training and strengthening the collection in the hands before working on it under the saddle. This is the beginning of teaching the horse to “close” the body, which will one day lead to collection.

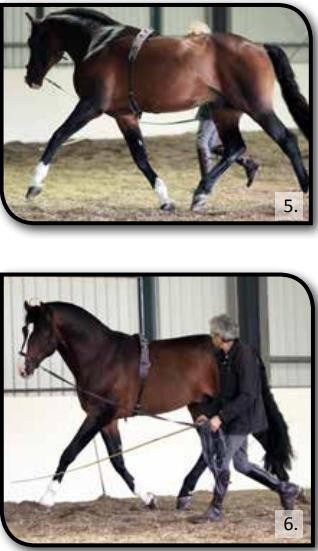

5. Manolo works Clint’s outside front leg with a bamboo stick to activate the outside shoulder and leg and create more room for the horse to step deeper under the body with the inside hind leg. Notice how loose the cord is – this encourages the horse to lengthen the neck, keeping the muscles soft and the throat open.

6. In the past, this horse was not handled much by hand. Clint doesn’t carry his neck the way Manolo would like, but he’s starting to learn how to find his own independent balance. Clint can move freely and he lifts his neck, but overall he is not stiff. Manolo doesn’t try to put the horse’s neck in the right position. Instead, he focuses on creating rhythm and activity by touching the front of Clint’s front inside leg with a bamboo stick. This eventually produces the desired result: Clint’s neck takes on an arched shape that suits Manolo at this stage.

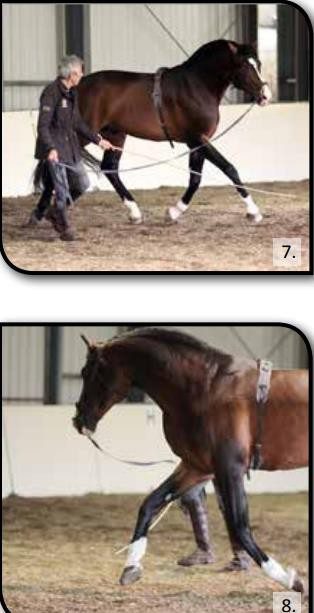

7. Manolo repeats the same exercise in the other direction to work both sides of Clint’s body. Pay attention to the position of Manolo – he holds the cord in the outside hand, and the bamboo stick in the inside. He touches the horse here and there to create a cadence, to activate his body and muscle memory.

Rice. 8. Clint shows more lift at the withers and more neck arch.

Rice. 9. In this photo, Manolo is moving Buddy on an 8-9 meter circle to the right. Manolo himself stands on the outside of the circle, a cavesson in his left hand, a bamboo stick in his right. He gently guides Buddy in a circle, making sure there is no resistance. Periodically, Manolo asks the horse to move from an 8-12 meter circle to a shoulder-in or shoulder-first three-track forward and out. When Buddy is done with this task, moving smoothly, relaxed and soft, Manolo returns to the 8-meter circle and repeats the shoulder forward or shoulder-in back to 12 meters. Manolo always guides this movement step by step in a very soft, direct manner. This walk exercise is a great way to help your horse understand what you are asking him to do at the beginning of learning to move sideways under the saddle.

How to get the most out of getting started in your hands? You need to keep the horse calm, encouraging him to accept your actions.

Before I can work with my hands and do different exercises, my horse needs to learn to move freely and softly at the walk, trot and canter in both directions on the lunge. She must also have an understanding of the basics of balance, rhythm and correct bending.

Once the horse is comfortable with lunging in a circle, I can start using the arena wall to move him in a straight line and introduce him to the work of the various parts of his body and how they can be mobilized with a bamboo stick for work in hand.

I use a simple bamboo stick, dry and light. I have several different lengths – 1,80, 2,45 and 3,65 m. The diameter where I hold on to is usually the same as the diameter of my index finger. The end with which I touch the horse is very thin and very light. The bamboo stick should be straight and without bumps.

When I introduce handwork into training, I try to keep everything as simple as possible. I start from a stop and ask the horse to go on, touching one of his legs. I stop her and again ask her to go, touching the other leg. I repeat stop-move-stop, touching the legs alternately until the horse responds calmly to the touch.

I want to desensitize the horse to the touch of a bamboo stick on his feet, take away his fear, and teach him that when I touch his feet in a certain way, I ask for specific reactions. I can ask for more connection, ask to step deeper under the body, step up or step back. If I put a bamboo stick in front of the front or hind legs, I ask the horse to touch it with his hoof every step and create his own rhythm. But before I ask for anything, I get the horse used to the bamboo stick.

My goal is to be able to touch all four of the horse’s legs during the stop, as well as various parts of the horse’s body: neck, chest, flanks, belly, rump, thighs, etc. I can scratch the horse with a bamboo stick to make it feel good, run it all over the body until the horse gets used to it. I do not force the horse to stand still and try to imbue it with my calmness and also calm down.

If the horse starts to feel like he’s being held back by the wall, I can return to the center of the arena where he feels confident thanks to the previous lunging lessons.

I work with the horse right and left. I never know how my horse will react today, tomorrow, the day after tomorrow – I always watch his responses using the lunge and wall.

How is the horse feeling today? Is she lethargic or active? Does it move evenly? Curved? Tense? Impulsive? You can work with the horse in a straight line, then stop and touch his leg. If the horse moves his leg, I praise him. I repeat – move forward, stop, touch the other leg. If she answers, I reward. For now, you should not pay attention to the direction in which the horse will move his leg; only a calm answer is important.

I have watched many horses accept this process as your moves are quick and without pressure. Next, I add work at a trot. I ask the horse to get up into a trot, then go to a walk and stop. While stopping, I touch each leg in turn.

It is important to be consistent in order to develop understanding and confidence in the horse. If we force the work, the horse may try to run away, and our training will not achieve anything. You need to move slowly, calmly and with concentration.

It is very important to make transitions between walk and trot so that the horse understands what we want him to do.

In this exercise, we are looking for softness in the horse’s body and correct posture. This is the key to all successful arm training. In order for the horse to have good posture and maintain softness and lack of tension, we must create regularity, balance and harmony in his body so that the horse can freely work his shoulders when we touch his hind legs. When the horse keeps his neck long, he has enough room to move forward and, most importantly, he can move smoothly. Softness is defined as the absence of tension or fixation in the muscles, keeping them relaxed and supple.

The horse must be able to use his neck for balance and to provide the necessary room for deeper steps under the body. This does not happen if the horse’s neck is shortened. If we restrain the horse and make him short in front, he will move on the front, on his shoulders and will not be able to keep straight. She will not be able to find independent balance and rhythm.

If this happens (even to a small extent), we will have problems when we start working on the transitions. As I mentioned earlier, correct posture from the very beginning is the key to building a strong, flexible and balanced horse.

Problems that arise while riding will also manifest themselves when working in the hands. The horse reacts more sluggishly with one of the legs, it is not straight, its body is not equally developed on the left and right. The result can be seen and felt in the hands and under the saddle.

What will we do (for example) if the horse does not move evenly and does not step under the body with the same depth of left and right hind legs?

If we carefully observe the horse, we will notice that the step taken by his left hind leg is shorter than the step taken by his right hind leg, and as a result, the horse takes a shorter step with his right front leg (what the hind leg does affects on the diagonal shoulder). Therefore, if we work with the left hind leg, then we work on the right shoulder, respectively, improving the entire body of the horse.

In the hands, we can act on any leg of the horse, asking him to work more actively. To help the horse activate the left hind leg to match the right, we ask the horse to move in a straight line and, as the left hind leg leaves the ground, touch it lightly at the hock. We observe the result and it helps us figure out if we are asking on time or too early (too late, too much or too little) and it helps us to improve our Sense and Timeliness.

To help the horse develop without harming his health, it is very important to observe what is happening with his body. Observe her muscles while moving and stopping, paying attention to the asymmetry: which side of the body is more developed, which shoulder, which side of the croup, which thigh, which side of the back of the head, which pectoral muscle, etc. These differences are a map that tells us about the development of the horse, about its problems that already exist or will arise in the future.

Working in the hands requires us to be patient, observant and flexible. Sometimes, when everything is going well, we may notice something that is not quite right and we need to think about how we can help the horse get better.

What if we start working on the piaffe and find that although the hind legs move well, the front legs leave a lot to be desired? Is the horse straining his neck and shoulders, and his body does not work harmoniously, as a whole mechanical movement? We need to reward the horse well for getting the hind legs working properly, as this is hard work (they have to bend well), but we also need to teach the horse to use his front legs in sync with his hind legs. So what are we to do?

To help the horse learn to work smoothly, with integrity and without tension, I end the reps, stop working on the piaffe, and bring the horse to the center of the arena. As I mentioned earlier, in order for a horse to move in an even and regular balance, his body must be soft and free of tension. Only in this way will the horse become elastic at the topline, be able to bend, round the loin and lower the croup, as is necessary for the piaffe.

Knowing this, I gently ask the horse to lower his neck and head, massaging the base of his neck to see if the tension is gone. I can also ask her to walk and then trot around me in an 8-12 meter circle (the circle should be comfortable for the horse, I don’t ask him to move in a smaller circle that is not comfortable for him) and carefully observe how the horse uses his body to move left and then right. I don’t rush her legs, but I want to see the rhythm, the softness and the right bend. When I understand that the horse is responding correctly and he has softened, I can resume work on the piaffe.

We must look at the whole body of the horse and make sure that every part of it works in harmony with the others.

When a horse lifts his neck very high, or drops it very low, or moves behind the vertical, he is telling us that he does not understand how to carry himself, or cannot find his balance using his neck. It shows us the weakness of the muscles of the neck.

The horse should lengthen the neck (from the withers to the poll) and shorten the body (from the withers to the tail). If we shorten the horse from the nape to the tail, then his body will eventually weaken and lose grace and elegance. The horse will not be able to find his balance and will develop bad posture, which in turn will create problems for us at every stage of training.

To keep the horse’s neck long and his body short, we can use hand exercises. They are like ballet drills for precision, strength and flexibility, and give better results than if you were trying to achieve it in the saddle.

I can encourage the horse to lengthen his neck by gently tapping the tip of his tail as he circles, asking him to raise his back by touching the base of his neck or belly. I can tap the sand vigorously with a bamboo stick parallel to the horse’s legs and ask him to move a little more forward. The movement of her body will cooperate with me, the horse will lengthen the neck for balance.

I can ask the horse to simply shoulder forward in a circle around me at the walk, or to shoulder in at the wall, allowing him to lengthen his neck as his body contracts as his legs step under the body. I can change direction by encouraging the horse to circle around the hind legs or do a quarter pirouette, asking him to take each step slowly and calmly, touching the leg I need as needed, ensuring even, synchronized strides.

I can ask the horse to trot in a straight line. By placing a bamboo stick in front of her front or back legs, I will encourage her to move more rhythmically, rounding her neck as her front kicks off the ground. I can take a second bamboo stick and work in straight lines on his front and back legs, or put one stick on the horse’s chest while I work on his hind legs to slow him down the arena wall.

There are many handiwork techniques available. For example, both ends of the cord can be attached to the cavesson ring so that the trainer can walk or run after the horse as it performs the piaffe and passage. But keep in mind that the horse must be ready for this and trust the trainer.

There are many options at your fingertips. This work helps us develop the horse’s confidence and attentiveness as his ability to understand what we ask him to do grows and the horse gradually discovers that we are honest with him, our requests are clear and precise.

By constantly observing the horse and working to keep his mind and body soft, we can deepen our bond with him and make our communication more effective, both on the ground and in the saddle.

Work in the hands should not be based on coercion. We must strive for harmony and use training to better understand our horses and find ways to make it easier for them to work under the saddle.

As a result of frequent correct work in the hands of Brolga, he is not frightened when Manolo works with a bamboo stick and a whip at the same time. He calmly and willingly performs a piaffe under his rider.

Manolo works with Brolga on a piaffe using a cavesson like this. so that the cord runs around the horse, both ends are attached to the nose ring. Manolo maintains light contact, prompting Brolg to remain soft and move ahead of the vertical.

Dynamico learns the Spanish step under the saddle – calmly and without tension.

Manolo Mendez (East); translation Valeria Smirnova