Learning to ride: get over your speed bumps

Learning to ride: get over your speed bumps

Our first riding lessons are usually difficult, but after spending a couple of dozen hours in the saddle, we begin to enjoy learning new skills and seeing the horse finally give us the answers we want. However, as we move steadily forward, sooner or later we run into our speed bumps on the way. Today I want to talk about them and how to overcome them.

You can (!) work at the training trot!

As always, first of all we will talk about dressage, because dressage is our ability to talk to the horse and hear the horse. Whether you are interested in pure dressage, show jumping or eventing, dressage always comes first. By now, you know your dressage position is important, but you may start to get frustrated because no matter how hard you work, your riding doesn’t get better. “How can that be?” you think. “I sit up straight in the saddle, I keep a straight line from my elbows to the corners of my horse’s lips, I do some simple side work to improve my horse’s flexibility, I work on dressage three or four times a week, but I don’t move anywhere. What’s wrong?

Relax. We’ve all experienced this. The way forward is not closed to you, that’s for sure. Here it is: you have missed the main part of your landing – your connection with the horse’s back. Use your seat to connect with your horse, not just to mechanically perform the movements of dressage riding. Before your next training session, take a mechanics lesson from the best professor – your horse.

Take her to a barrel, a small levada, or just take it on a lunge. Let the horse stretch its legs while you watch it move. Give her time to calm down, then use your voice to encourage her to show you all three gaits. At each gait, at each pace, first observe the hips, then the shoulders of the horse. When she walks, what do her hips do? How are the four steps formed? How will her body feel under you when the hip moves in a certain way while the opposite shoulder moves forward? Visualize these moments, remember what the horse’s body is doing in all three gaits, and then you can “rebuild” your landing.

Let’s say you still have problems with the training trot. While you were watching your horse, you noticed that when his hind leg moves back, the hip on the corresponding side drops. And the second hind leg at this time goes forward, and the thigh on its side rises. Now watch the shoulders of the horse at the trot. The shoulders sway but do not swing up and down like the hips. By now, you will hopefully have an “aha!” moment. When you trotted, you were actually sitting on something that didn’t move up and down in a direction, but made a different movement. Your task now is to figure out what your seat and loin need to do to stay in contact with your horse’s back during the two bars of the trot.

I don’t promise you will feel the horse’s back fully (just for now), so let me give you a hint: if the horse’s hips move in a certain way, then his shoulders move in a certain way at the same time. If her left hip lifted, her right shoulder would move forward—and that would bring your right sitting bone down. In other words, don’t try to lift the left ischium. Instead, press your right seat bone forward and down as the horse’s right front foot hits the ground. The answer to the question is: you should let your horse push your seat bone up, when his hip goes up, it will be easier for you to relax, so you can stay in the saddle.

This is just one example. There are a number of movements you will need to make in each of your horse’s three gaits in order to stay in contact with his back at all times. I want you to develop understanding by watching and feeling. I have written books on this subject (as have many others). However, before reading, take a lesson from your horse – he is a much better teacher than any human being.

Why is it harder to trot onto an obstacle?

Another speed bump you may encounter is that when you jump, you will always find it easier to jump 90 cm from a canter than 60 cm from a trot.

You can ask yourself the question – why bother jumping from a trot at all? Don’t we gallop in tournaments? Cantering, no doubt, but trotting should be included in training for a number of reasons. First of all, approaching a small (about 60 cm) obstacle at a trot instead of a canter will reduce your speed. A lower speed increases the emphasis on jumping technique rather than momentum, and this teaches your horse to jump more efficiently. Also, because the jumps are lower, you reduce the impact of the landing, which helps keep the horse healthy. “Okay,” you might say, “I understand all this, but when I try to trot over low obstacles, I always either fall on my neck, ahead of the horse, or behind him. What to do about it? I will answer! This happens when the horse loses the rhythm of the trot in the last few steps to the obstacle. And that’s when you lose the rhythm, and certain unpleasant things happen.

My advice to my students is the following. First of all, remember that you should always look at the barrier between your horse’s ears until it disappears from view. Usually, when the obstacle disappears from view, it means that it’s time for you to follow the horse’s jump. But in this case, the barrier is so small that it will be out of sight long before you arrive at the desired repulsion point. When this happens, start counting the steps the horse takes before jumping. Be careful, try to keep the relief even as you count. There is no correct number of steps; the number will depend on how tall you are, how high your horse carries his neck and the size of the obstacle. The quantity is not important, but the rhythm is extremely important.

Trotting over low obstacles can be an important addition to your skill set.

clock in your head

Another speed bump that riders have to deal with is, quite literally, speed during the cross-country. You want to go to the next level, but you constantly have problems with the cross. Twice you were the slowest rider, and then you got a warning for riding too fast on the cross country. How can you be?

What happened? What happened is that you moved to the next level without developing your sense of the necessary speed of movement, which is necessary for this level. To speed things up, you need to slow things down. Let me explain: find a field where you can gallop on good ground in a straight line for at least 400 meters. In an ideal world, the field would be a large oval or rectangle. Place a marker down one corner of the field and measure from it, say 350 meters. Place another marker at this point. Now you have a speed trap where you can find out what 350 meters per minute (m/min) is like when you are in the saddle. Set up a 400 m/min speed trap somewhere else in the field, and then somewhere else. Make marks for 450, 500 and 520 m/min.

Have you already guessed where I’m going? We’ll start with the speed you’re most comfortable traveling at, 350 m/min. This is achieved by running the speed trap distance in one minute using your stopwatch. Horses rarely run with exactly what you set, and you will need to find out how your horse feels at each speed level. On days when you are working on the horse’s fitness, train at these different distances until you can determine how fast the horse is moving (eg 400 m/min).

Don’t work for long periods in the 500 and 520 mpm traps when you first begin this challenge, because the horse’s fitness needs to improve a little to be able to handle the increased workload at higher speeds. In the end, she will be able to work at different speeds without difficulty. At some point, you no longer need to look at the stopwatch to know that you are moving at a certain speed.

One training tip: While warming up, you can work on the slowest speed trap. Later, the horse should be comfortable transitioning from 350 m/min to 520 m/min and then back to 350 m/min. This exercise mimics the demands of modern cross-country running, where you will need to repeatedly change your movement towards and away from you during the course.

So, I hope that now you will have your own “clock in your head”. (This expression came from a treadmill – that was the name of a jockey who could travel 400 m at a certain speed without looking at his watch). But how now to combine a sense of speed and jumps? After all, this is what caused you problems in the first place? Let’s repeat the process, but this time with jumps. Place a vertical in the center of each speed trap (provide a trap on both sides to jump in both directions). Set the height to match the requirements of each level – Prep, Preliminary, etc. Warm up at the lowest hurdle and then move on to the next one. Before entering any obstacle, make sure that you have activated the clock in your head and that you are driving at the correct speed. Focus on maintaining a constant speed as you ride, jump, and back away from each obstacle. I want to emphasize this: regardless of the size of the jump in the speed trap, you need to enter, jump, land and leave at the same speed. My idea is that you can only do this when your horse is constantly in balance. When your horse is in balance, the speed bumps disappear.

Learning to ride properly does not involve a smooth upward curve. You should expect to struggle with problems from time to time, but if you stick to the right training and thoroughly study every issue that arises, you can persevere. The feeling of satisfaction you get will prove to you that you have overcome difficulties with honor and have benefited from them, and your horse will appreciate your efforts, starting to work better than ever.

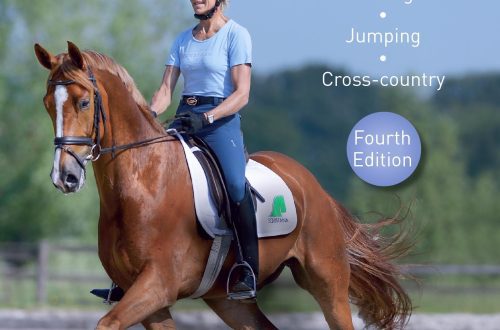

Trotting over low obstacles is a great exercise for you and your horse. In the photo we see how the horse moves in a straight line, calmly, evenly. The horse is focused on work. Don’t forget to watch your landing when you approach an obstacle. If you change the rhythm with which you eased, your horse will lose the rhythm of his trot, which will make jumping even a small vertical awkward. The rider’s eyes are correctly focused. The top of the obstacle had just disappeared from view between her horse’s ears, but the horse hadn’t had time to push off yet. The horse needs to trot one or two more steps to get to the correct take-off point (in theory, it is located at a distance equal to the height of the obstacle). To better trot small obstacles, count the remaining steps your horse will take after the top pole is out of sight, and also concentrate on keeping the rhythm.

The rider demonstrates what an excellent canter leg position looks like. Obviously, when the speed increases above 500 meters per minute, the stirrups will have to be shortened. However, for Preparatory and Intermediate levels, I would advise not to change the length of the stirrups (they are better to be the same in both cross-country and show jumping). Take your feet out of the stirrups, let them hang straight down, and adjust the bandage so that the stirrup touches the ankle bone. You need to practice maintaining the right pace using what I call speed traps.

Jim Wofford (source); пerevod Valeria Smirnova.