How to evaluate a horse’s conformation

How to evaluate a horse’s conformation

Can highlight five main criteria to evaluate the exterior of a horse:

1. Balance (ratio of parts of the horse’s body);

2. Structural correctness (setting the legs);

3. Movement;

4. Musculature;

5. Sex / breed type.

Balance is an important aspect to evaluate when studying the structure of the horse. It provides the quality of the horse’s movements and is largely determined by its skeletal structure. Balance refers to the even distribution of the horse’s musculature and weight from front to hindquarters, from topline to underline, and from side to side. It does not depend on the mass of the horse. It is based on the correct angles and proportions of different parts of the body. A horse can be light or heavy and will be considered balanced if its skeletal structure allows it to evenly distribute the available weight. Proper balance allows the horse to carry himself in a way that provides easy maneuverability, more power, and smoother movements.

Structural correctness is critical to keeping the horse intact, and also ensures the correctness and cleanliness of the movement. It is defined as the correct structure and alignment of the skeleton (especially the limbs). Structural correctness is closely related to balance and affects the course of the horse.

of movement tell us how the horse moves. Both cleanliness and quality of movement are evaluated.

Musculature when evaluating a horse’s build is not as important as balance and structural correctness. The quantity, quality and distribution of muscles are assessed by looking at the horse from the sides, front and back.

Assessing breed and sex type, find out how well the horse’s breed and sex characteristics are expressed. Most breeds have unique qualities that can be used to identify their representatives. Evaluating a horse by type, the expert finds out how close it is to the “ideal” representative of the breed. This criterion is of particular importance for horses that take part in shows where breed is judged.

1. Is the horse balanced?

The first priority when looking at a horse is to determine its balance. The horse must carry the same weight on the front and hindquarters and on the top and bottom lines. This is determined by its skeletal structure, which allows you to maintain the correct proportions of the horse’s body parts. The neck, shoulder, back and hip should be about the same length, and the top line of the horse should be shorter than the bottom line (fig. 1).

Rice. 1. A horse with perfect balance. All solid white lines are approximately equal in length. The dotted white line (topline length) is shorter than the dashed purple line (underline length).

A common fault that negatively affects the balance of the horse is the back, which is too long in comparison to the neck and hips.

An important ratio to consider when analyzing balance is the ratio of the top line to the bottom line. The topline is measured from the withers to the loins, the underline from the point under the belly between the front legs of the horse to a point approximately at the level of the knee joint (Fig. 2). A longer topline indicates that the horse has a long, weak back (a long back is often poorly muscled). The long line of the back makes it difficult for the horse to engage the hindquarters in motion, and the role of engaging the hindquarters cannot be overestimated. If the horse cannot bring his hind legs well under the body, his weight is shifted to the front. This reduces the power and agility of the horse, which, among other things, becomes more shaky under the saddle.

Rice. 2. The horse in the photo above has a good conformation – the top line is shorter than the bottom line. Below – a horse with a long and weak back (top and bottom lines are the same length).

The next important criterion for balance is the height of the croup and withers, which should be approximately the same. The horse may have a higher withers position than the croup, but without a significant effect on the balance.

If the horse is “overbuilt” (withers below the croup), more weight will be shifted to the forehand. Such a horse loses in maneuverability and momentum (Fig. 3). Shifting weight to the front can lead to lameness in the future.

When evaluating young horses, remember that they will grow up faster at the croup than at the withers. Weaners, yearlings and two year olds can be “rebuilt”, but the withers as they mature are likely to catch up with the croup in height.

Rice. 3. The horse in the top photo is balanced. Below is a “rebuilt” horse (croup above the level of the withers).

Analyzing the balance, it is necessary to evaluate the depth of girth in the region of the heart – this is an important indicator of the ability of the horse’s body to contain the heart, lungs and other vital organs. It is desirable that the horse has a deep girth. If we draw lines from the withers to the bottom of the chest and from the bottom of the chest to the ground, they should be about the same length. They should also be longer than the groin girth line (Fig. 4).

Rice. 4. The depth of girth in the region of the heart is a measure of the body’s capabilities. Ideally, it (white line) should be approximately the same as the length from the chest to the ground (blue dotted line) and exceed the depth in the groin area (red line).

Proportions to consider when determining balance

When determining if a horse is balanced, it is important to study some of the proportions and angles of his body. One of them – shoulder slope horses.

Shoulder slope is closely related to other body parts and proportions, such as back and neck length. It is measured by the angle of the horse’s shoulder blade (usually measured from the top of the shoulder blade at a point near the withers to the point of the shoulder).

If we draw two lines (one from the top of the shoulder blade to the point of the shoulder, the second from the top of the shoulder blade down, perpendicular to the ground), then the angle of the shoulder should ideally be about 45 degrees (Fig. 5).

The slope of the shoulder directly affects the length of the horse’s stride and its smoothness. A shoulder that is too straight prevents the horse from easily reaching forward with its front legs, and therefore its stride is short and sharp. Horses with beautifully sloping shoulders have a free flowing, smooth, long stride, as they can carry their front legs far forward.

Rice. 5. The horse in the first photo has a more ideal shoulder (about 45 degrees of inclination). The horse in the photo below has a much steeper, straighter shoulder.

The shoulder is also affected shape and main exit points of the neck. On fig. 6c shows the desired ratio of the length of the upper and lower neckline, which is 2:1. The horse in fig. 6a has a low neck opening (white arrow), her neck is not as long and graceful, and she has a more straight shoulder. The horse in Fig. 6b neck exit high.

Fig. 6a.

Rice. 6b.

Fig. 6c.

The slope of the shoulder greatly affects the appearance of the horse’s neck. In a horse with a steep shoulder, the withers often merge into the neck at a much closer point than in a horse with a good shoulder slope. The result is a horse with a shorter neck line and a longer back. Due to the longer back, such a horse has both a shorter stride and a forward weight. A short neck is usually an undesirable characteristic as it causes a lack of flexibility in the neck and is also usually associated with a straight shoulder.

Another important point to consider when studying the horse’s neck and shoulder is how the neck emerges from the chest at shoulder level. A high exit is preferred – this provides a good slope of the shoulder, the neck becomes more graceful. If the neck exit is low, the neck becomes heavier at the base, the shoulder is usually straight.

We must not forget about the ratio of the length of the upper neck line to the lower one. The top line of the neck is measured from the back of the head to the withers, and the bottom line is measured from the throat to the shoulder. The ideal ratio is 2:1. This allows the horse to have a more sloping shoulder (with the withers further away from the point of the shoulder), to bend at the poll and to round the neck (Fig. 6b).

A horse’s neck with a longer underline is called “deer”. This conformation trait is undesirable, as it is usually associated with a straight shoulder and a lack of suppleness and the ability to lower the head.

When examining a horse’s neck, it is important to consider the ratio of the junction of the head and neck to the length of the head. The connection of the head and neck is measured from the occiput to the lower jaw and should be about half the length of the horse’s head (the line from the occiput to the snore). If a horse has a thick throat, it limits its ability to bend at the poll. Such horses, if their neck is bent at the occiput and the nose is brought closer to the vertical, may experience difficulty in breathing.

Rice. 7. A horse with a refined connection of the head and neck. The distance from the back of the head to the lower jaw is less than the distance from the back of the head to the snore.

Important factors in evaluating a horse’s conformation are − hip length and inclination. The horse’s thigh should be about the same length as its back.

The bigger the hip, the better – more power, more muscles to propel the horse forward. In virtually all equestrian disciplines, horses exhibit moves that require strength and power. The larger the hip and the better it is formed, the more power it will provide.

Ideally, the horse should have a “nicely sloping” hip and croup. The slope of the hip should be about the same as the slope of the shoulder. A horse with a too vertical hip will have trouble bringing the hind legs under the body, while a horse with a too steep hip (“hanging croup”) will not be able to move in a way that generates the necessary power. In addition, the thigh should connect fairly low to the lower leg.

Rice. 8. Look at the angles of the hip joint. In the image on the left, a good hip (good angle and good length), on the right, a very short, steep hip.

How important is the head in assessing balance?

The main function of the head in terms of horse movement is as a pendulum for balancing. Therefore, it is important that the head is in proportion to the rest of the horse’s body. The head of the horse is too heavy (considering the length of its neck) – no other animal has such proportions. She weighs an average of 18 kg. If the neck is of the proper length and the head is in proportion to the size of the rest of the body, it can function as a balance during movement.

Although the evaluation of the head is important, both in terms of proportion and finesse, it must be understood that the head is not as critical in determining balance as the other proportions previously discussed. Proportionality and attractiveness of the head should not take precedence over other characteristics of balance or structural correctness.

Rice. 9. From above – the ideal head (pay attention to the distance between the eyes and the position of the eyes relative to the head). Below – the head is too narrow in relation to its length.

A good example of imbalance is the “bobbing” of a lame horse’s head. When a horse limps on its front leg, it uses its head to pull its body up (lifts it up and pulls it away from the injured leg). When a horse limps on its hind leg, it lowers its head and pulls it in the direction opposite to the lame hind leg. In both cases, the head works like a pendulum, taking some of the weight off the injured leg.

Because the horse uses its head for balance, it is important that its weight is in proportion to its body. When a horse has a too heavy head, he is usually unable to take the weight off the forehand (so it will be difficult for him to succeed in the sport).

“Ideal” heads vary slightly between breeds, but the basic principles regarding their size and shape are fairly universal. The distance from the back of the head to the middle of the line drawn between the eyes should be half the line drawn from the middle of the line between the eyes to the middle of the line drawn between the nostrils (the eyes should be approximately one third of the distance from the back of the head to the nostrils). The width of the horse’s head from the outer edge of one eye to the outer edge of the other should be approximately the same as the distance from the occiput to the horizontal line drawn between the eyes. Such a structure is not only attractive, but also physiological.

Common structural characteristics of the head that are generally considered faulty are hook nose and heavy jaw. With hook-nosedness, the front side of the head is rounded (Fig. 10.2). This usually does not affect the working qualities of the horse, although such a head may be heavy. A heavy (too large) jaw makes the horse’s head look less attractive, adds weight, and prevents the horse from bending at the poll.

Rice. 10. Above is a beautiful, refined head shape. Below is a slightly hook-nosed head.

The following factors are the size of the nostrils and the size and shape of the eyes.

The nostrils should be large and round to provide maximum oxygen intake when the horse is working and panting. It is also desirable that the horse has large dark eyes set far apart on the outer sides of the head – this will provide him with good vision.

To understand the importance of eye placement and size, you need to know about the horse’s field of vision. Horses have more monocular vision than binocular vision. The horse sees each picture well with each eye (monocular vision), but poorly sees what is in front of it with both eyes (limited binocular vision). This is why a horse with small and/or too close eyes has a limited field of vision.

Rice. 11. Field of view of the horse. binocular vision. monocular vision. Blind spot

2. How to evaluate structural correctness?

The structural correctness of the horse is determined mainly by the structure and position of the bones of its limbs. The legs of a horse are of the utmost importance in any equestrian discipline. No legs, no horse. Any conformation defect will cause deviations in how the horse absorbs impacts on the ground as it moves. Conformal defects affect the way the horse moves and can also (over time) cause lameness due to the excessive stress that occurs in certain areas of the body during sports activities.

The horse carries about 65% of its weight on the forelegs, making the forelegs more susceptible to injury caused by physical injury or shock from kicking the ground. Conformal defects affect the occurrence of deviations in how the horse moves and how he puts his hooves on the ground, they affect how the force from hitting the ground travels up the leg. The more structurally correct the horse’s legs are, the more evenly distributed the impact is and the less likely the horse is to be injured by chronic or acute illnesses.

The structure of the front legs

When analyzing the exterior of a horse’s legs, it is important to look at the horse’s side, front, and back.

When you examine a horse’s legs front (facing her), you should be able to draw a line from the shoulder down to the ground, which will bisect the leg (fig. 12). The hoof and knee (wrist) should point forward and a straight line from the shoulder should bisect them clearly. The width of the hooves in the area of the sole should be approximately equal to the width of the leg as it exits the chest. Deviations from this ratio cause additional loads on different parts of the legs.

Rice. 12. The exterior of the front legs (setting) is determined when viewed from the front. From left to right: ideal position; size; outward-curved postav; narrow chest and size; narrow postav; X-shaped setting; clubfoot. A line drawn from the point of the horse’s shoulder must pass through the center of the elbow, carpal and fetlock, and hoof.

It is important to understand that any conformation defects can cause lameness because they cause excessive pressure that is focused on a specific area of the leg. This is how horses with a narrow set put their hoof on the outer side wall. A corresponding increase in pressure on it can lead to defects such as toad, ossification of the coffin cartilage and heel injury. The other side of the coin: horses with a wide set step on the inside of the hoof. The weight is redistributed to this area, which can lead to the development of a toad and ossification of the coffin cartilage.

Defects in the exterior of the knees (wrists) – arched outward set, x-shaped set, etc. – cause increased tension in the carpal joint and the ligaments and tendons attached to it. With an x-shaped set (knees turned inward), the horse twists the metacarpal bone, fetlock and pastern. This prevents an even distribution of the load when the hoof hits the ground. Area that absorbs bоmost of the impact is damaged. The horse makes uneven movements with its legs.

The horse’s legs should be examined and on the side (Fig. 13). An imaginary straight line drawn down from the center of the shoulder blade should pass through the front edge of the knee and bisect the hoof. There may be defects such as substituted or set aside legs.

If the legs are out, the horse will set them too far forward, putting pressure on the hoof, carpal and fetlock joints (the horse will have to arch them out). This set-up is caused by conformation defects and can cause soreness in the hooves.

A horse with outstretched legs will put the hooves further under the body, which will increase the load on the ligaments and tendons of the legs. This will also force the horse to put more weight on the forehand. The horse may limp and/or stumble frequently, and its steps become short and irregular.

It is important to understand whether there is a defect in the horse’s conformation, or whether he simply chose this way of standing for himself. Make sure the horse is standing naturally and upright before concluding that he is putting his front legs in or out (some horses may adopt this posture because they are not set correctly, some may be suffering from a disease and try to relieve pain).

Two other vices that can be seen standing to the side of a horse are a sunken pastern and a goat. If a straight line does not bisect the knee and runs in front of it (i.e. the knee looks backwards), it is called a sunken pastern. This deficiency is considered the more problematic of the two, as it puts undue stress on the ligaments and tendons of the legs, as well as pressure on the front of the carpal joint, making the horse more prone to develop osteoarthritis of the carpal joint. If the line is behind the knee, the knee appears to be bent even when the horse is standing with all its weight resting on the front legs, this is called a kozinets. With a kozintsa, increased pressure is also exerted on the tendons and ligaments of the horse’s legs.

Rice. 13. Exterior of the front leg, side view: ideal position; the leg is substituted; the leg is set aside; kozinets; sunken metacarpus. The vertical line runs from the shoulder through the elbow and the center of the hoof.

The structure of the hind limbs

The hind legs are examined from the side and standing behind the horse.

When you inspect the horse behind, you should be able to draw an imaginary straight line from the ischial tuberosity through her hock and fetlock (Fig. 14). The hooves of the hind legs will not be as straight as the hooves of the front (it is normal for them to turn slightly outwards).

Problems associated with a cowhide or narrow hoist are mainly due to additional stress on the limbs and joints (if a horse has a cowhide, it can provoke the development of spar and fills), as well as mechanical shocks of the hocks against each other during movement. Horses with buckled hauls have the opposite problems of narrow and cow hawks. These horses often fail to properly use and push off their hindquarters (this affects their working ability).

Rice. 14. Ideal postav; wide postav; narrow postav; arched postav; cow (x-shaped) set. A vertical line drawn from the ischial tuberosity should run through the center of the hock, the center of the metatarsus and pastern.

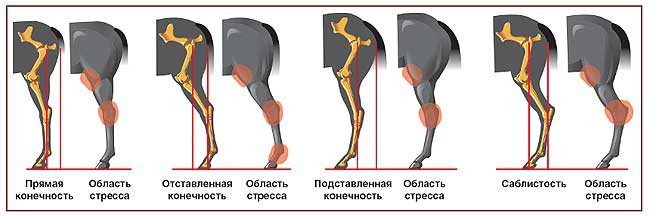

When examining the hind legs of a horse on the side (horse must be level) you must draw an imaginary line perpendicular to the ground from the hip joint through the hock and fetlock. This structure of the hind legs allows the horse to carry weight well on the hindquarters and bring it down when he moves to develop maximum power. A saber horse has too much hock angle (he will look like his hocks are too bent even if he is standing straight). If the angle of the hock is adjusted to a normal position in a saber horse, its hind legs are likely to become set back. This puts extreme stress on the hocks and the tendons and ligaments that surround them and can lead to diseases such as kurba, spar or bulge. The opposite flaw to saber is a straight stance, in which the horse’s legs are “straight”, the angles of the hocks are practically open. The hock joint has a large load, which contributes to the appearance of spar and fills.

Rice. 15. Direct, substituted, set aside and saber set.

Lower leg assessment

Assessing the limbs of the horse (both front and rear) is the angle of inclination and the length of the pastern.

Grandmas work as shock absorbers when the hoof hits the ground; the health of the horse’s legs depends on their condition. The angle of the pastern usually corresponds to the angle of the horse’s shoulder and should be about 45 degrees from the horizontal line on the ground (fig. 16a). To absorb shocks well, the headstock must be sufficiently long and sloping. An overly square pastern (often with a short pastern) does not soften the impact of the hoof on the ground, and the horse’s joints are subjected to concussion, which can lead to periarthritis, sesamoid fractures, joint pain (Fig. 16c). Straight pasterns also affect the navicular bone, causing it to come into contact with the short pastern bone, resulting in bone erosion or bone spur formation. Although short and straight headstocks are associated with various problems, it is also not desirable for headstocks to be too long or too sloping (Fig. 16b). In horses with this problem, the fetlock joint flexes excessively, causing damage to the articular and surrounding structures.

Rice. 16a. Perfect headstock angle.

Rice. 16b: Slant headstock.

Rice. 16c: Headstock too straight.

Need to check pastern angle and hoof angle, which should be about the same. A hoof with a more right angle in relation to the angle of the pastern is called a butt (Fig. 17). Such a hoof will not only change the way the horse walks, it will also make him prone to lameness!

Rice. 17. A horse with a front right hoof.

How does structural correctness affect movement?

The appearance of the legs greatly influences the movements of the horse. A horse with “correct” legs has the maximum range of motion and moves cleanly and correctly without any interference (e.g., not kicking the leg). Horses with structural abnormalities in leg conformation tend to move unevenly. So, horses with clubfoot, as a rule, make arched swings with their legs (the horse bends the leg at the carpal joint and raises the metacarpus under itself, and due to the peculiarities of the set, the lower part of the leg from the knee goes outward in an arc). But this is not as serious as the mark of a mature horse. In this case, the lower part of the leg goes in an arc directed inward. Such a horse knocks with its front legs against each other (we note that the foal’s mark often corrects with age, as the muscles develop). Narrow-stalked horses tend to “twist” their legs while moving, or cross one front leg in front of the other, and tend to thump (fig. 18).

Rice. 18. Horse “A” has perfect leg conformation (it moves straight). Horse “B” has a sweep, its legs are caught during movement. Horse “C” has clubfoot (hooves pointing outward and legs arching). Horse “D” has a narrow stance – its track “curls”.

3. Assessing horse movement, it is important to look at it from the side to determine the width and quality of the step. In some equestrian disciplines and in some breeds (eg Thoroughbreds), the stride should be long and flat, with little work in the carpal joint (Fig. 19a). Horses of other breeds (such as Arabians) should actively flex their forelegs at the carpal and elbow joints and raise their legs higher (Fig. 19b). It is important for any horse to be able to place the hind legs well under the body during movement! It is also necessary to observe the movements of the horse from all sides to see if he “knocks” his leg on the leg, if his legs touch during the movement.

Rice. 19. (a): the horse does not make pronounced movements of the carpal joint and elbow with a long stride; (b) – complete opposite.

4. Musculature assessment

The volume and quality of the musculature must be assessed, but this indicator is not as important as the balance, structural correctness and movement of the horse. The degree of muscularity is largely determined by training and breed affiliation.

When evaluating the musculature, we evaluate the chest, upper arm, lower back, knee and lower leg. In the “ideal” on the chest you will see a deep “V” (Fig. 20).

Rice. 20. The arrow points to the horse’s well-defined chest muscles (deep “V”).

On the hind limb, the musculature should be clearly defined, but not coarse. The muscles around the “knee” should be the widest part of the horse’s leg when viewed from behind (fig. 22). The musculature around the inside and outside of the lower leg should also be broad and well defined. In general, it is desirable for the horse to have a smooth, well-defined muscle structure throughout the body. It is also desirable that the muscles of the upper arm and lower leg are clear, long and smooth, and not short and protruding.

When viewed from the horse’s side, the musculature of the back and loins should appear smooth and crisp, not weak. The muscles along the entire topline should be smooth, without depressions (Fig. 21).

Rice. 21. Areas in which the horse’s musculature is assessed when viewed from the side (shoulder, loin, “knee”, shin).

Rice. 22. When viewed from behind, the areas indicated by the black arrows should be the widest.

Conclusions

Horse conformation evaluation includes an analysis of the specific breed and type of horse for balance, structural correctness, mode of movement, musculature, and possibly breed and sex type. Breed and sex types were not discussed in our article as they are generally the least important factor in assessing conformation and can vary greatly between breeds. Essentially, breed type simply indicates how well a particular horse represents the ideal standard within its breed.

Proper conformation is important because it is what keeps a horse balanced, powerful and agile, and healthy throughout his life. Evaluating a horse based on its build should give an idea of how the horse can perform and how “whole” it will end up being. There are exceptions to every rule, and of course, you can know horses with a bad conformation, which, no matter what, perform well in the sports arena, and horses with crooked legs that have never limped in their lives. However, one way or another, the assessment of the structure of the horse remains one of the most reliable prerequisites for the presence of the athletic ability of the horse, as well as its potential for maintaining health.

Kylie Jo Duberstein, Assistant Professor, Animal & Dairy Science (source); translation by Valeria Smirnova.

- Korolushka 25 September 2022 of

About the “knee” blood from the eyes Answer