How do horses age?

Aging horses

We’ve all heard about America’s statistical aging—when the baby boomer generation reaches the age of 40, the median age of America’s population will begin to decline steadily. The same has happened in recent years with horses. Because 100 years ago they were working animals and were rarely kept after their productive years were over. Now horses are not only working and sports partners for us, but also friends. And it becomes more and more important for us to help them maintain their health in old age and extend their lifespan, as long as they can enjoy the “quality” of life. Modern veterinary science contains a vast array of knowledge and methods that can help us.

Currently, most of the horse population remains active to one degree or another. even between 20 and 30 years old, and these animals are priceless to us. Not only because older horses tend to be calmer than their younger counterparts, their experience, knowledge and wisdom make them ideal teachers and wonderful friends. Ask anyone who owns an old horse; and he will probably tell you that she is worth her weight in gold.

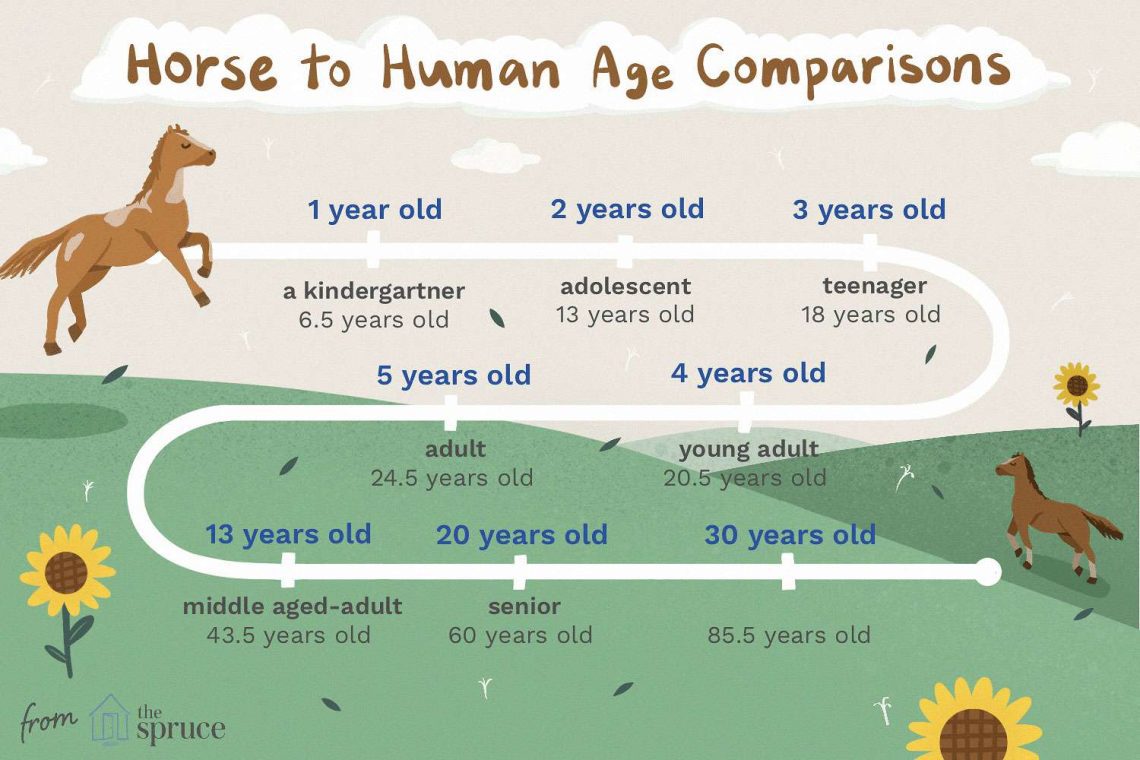

Horses age differently than humans. Compared to us, they have a very short childhood, a long and active adult period, and often a quick death from a sudden illness. The average life expectancy of a horse is considered to be about 24 years; but, as with humans, chronological age is not always a good indicator of biological age. Some horses are still active at 35, while others show significant signs of aging at 15.

Genetics play a big role here. As a rule, ponies live longer than horses, and some breeds (for example, Arabian) have a reputation for longevity. But in the duration of a horse’s life, an important role is played by good care. Those horses that have received preventative care throughout their lives, including vaccinations, dental care, good nutrition, and in particular strict parasite control, reap the rewards in old age. (Many researchers, by the way, believe that modern deworming agents have contributed more to the horse’s longevity than any other factor.)

This does not mean that older horses do not have health problems. Researchers have found that more than 70% of horses over 20 years of age have age-related diseases that require special care. Indeed, it’s perfectly reasonable to assume that your old horse is probably suffering from some of the annoying symptoms that old people also experience. But in fact, we are just beginning to understand all the physiological changes that accompany the aging process in horses.

Until recently, there has been little to no research into equine geriatrics, but a Rutgers University in New Jersey team led by Karyn Malinowski, PhD, has spent several years studying more than 20 elderly mares in the herd at the university.

“The goal was to improve the welfare of the geriatric horse,” Malinowski announced. She noted that her research is important not only for horses, helping them live a long and healthy life, but also for obtaining information about the aging process in humans. Horses have been found to be good models for studying Homo sapiens aging because their aging process is three times faster than our own and, like us, they enjoy being on the move. The laboratory animals on which human aging research has traditionally been based, such as rats, are unsuitable subjects because, according to Malinowski, “they hate to move unless absolutely necessary, and age about 30 times faster than us.” The link between human aging and horse aging may mean that we will get much more information and be able to expand related research in the near future.

How do horses age?

As horses get older, they experience a series of gradual but irreversible changes. Due to the weakening of the synthesis of collagen, the main protein of the body surface, the skin becomes flabby, “folds” are formed, and the lower lip hangs down in a peculiar way. The descent of the roots of the teeth, together with the atrophy of the postorbital and periorbital adipose tissue, leads not only to the appearance of depressions above the eyes, but the very expression of the muzzle takes on a dull, depressive look. After the destruction of collagen, muscular dystrophy comes, and the back sags in the saddle area. Many older horses develop gray (actually white) hairs around the eyes, temples, and nostrils.

It is common for older horses to develop cataracts, but they rarely cause complete blindness. The lens loses its transparency, but vision is less important to the horse than smell or hearing, so older horses with visual impairments tend to do very well.

Inside, there are even more changes. Although there are exceptions, aging usually weakens the cardiovascular system, reduces physical capabilities, and disrupts the absorption of nutrients. A number of researchers believe that aging causes the most severe damage to the digestive tract and the skeletal system. The immune system also takes a hit, becoming unable to protect the horse from viral and bacterial infections, so older horses are more susceptible to respiratory problems, allergies, wound infections, and even skin infections such as candidiasis (thrush).

Eventually almost every horse gets arthritis. This chronic degenerative cartilage disease compromises both joint mobility and load-bearing capacity. Arthritis can be disabling, although if detected early it can be successfully treated with injections of polysulfated glycosaminoglycans (PSGAGs—trade name Adequan) or sodium hyaluronate. In some older horses, symptoms of arthritis are mild – slight stiffness in the morning if it was cold, or if they spent the night in the stall without moving. For others, arthritis may present with lameness caused by problems such as growths on the headstock (toad) and spar.

Anti-inflammatory drugs, proper foot care, a thick layer of bedding (and light shoes if the horse continues to work) can do a lot to keep the old horse’s joints comfortable.

In addition to arthritis in the joints slows down renewal of cartilage, and the tendons and ligaments of old horses lose their elasticity. All these conditions impede the mobility of the old horse, reduce his enthusiasm and the stability of sports results. Muscle mass also tends to decrease, muscles become flabby.

A serious problem for older horses is loss of condition. Poor dental health, poor parasite control, and chronic illness can all contribute to this. A gradual decrease in the absorption of nutrients in the digestive tract (as a result of chronic parasite damage in the past or due to subtle changes in the digestive process) interferes with weight gain. In addition, many older horses lose their appetite, to the point of becoming anorexic. Therefore, once an old horse’s ribs have already begun to stick out, it is very difficult to get him to gain weight again.

The most important thing is regular monitoring of the health of the animal’s teeth. The horse’s teeth are designed in such a way that they continue to grow throughout life, but often the rate of wear exceeds this growth. As a result, it may turn out that the chewing teeth are so worn out that they cannot be chewed. Horses fed dry hay and grain should be examined more frequently than those fed grass in the pasture, but all older horses should have their teeth checked and sharp edges filed at least once every six months. Problems such as broken or missing teeth and sores in the mouth should also be looked out for. After all, if problems with teeth interfere with the horse chew food, colic or blockage of the esophagus may occur at any time.

Very old horses may lose the ability to chew at all. Fortunately, they can be fed grass meal pellets, beet pulp, ground grains, which are soaked in water and given as a thick or thin porridge.

Tumors

Pituitary and thyroid tumors are next on the list of the most common problems. In a 1989 study by Sarah Ralston, VMD, PhD, ACVN, and colleagues, over 70% of horses over 20 years of age had at least subclinical signs of one or the other. Although there were no obvious symptoms, a blood test revealed changes in blood glucose and cortisol levels. Thyroid tumors are more common appear in geldings, and for mares, pituitary tumors are more characteristic. Typically, these tumors are benign and slow growing, but insofar as they affect the secretion of certain hormones, they can have a profound effect on the health of older horses.

Both types of tumors can cause impaired glucose tolerance and reduced sensitivity to insulin, the hormone that regulates blood sugar levels. As a consequence, blood levels of both glucose and insulin become abnormally high, and the horse tends to experience increased thirst and an increased urge to urinate.

A horse with a thyroid tumor has an increased risk of obesity, lameness, and the growth of a tumor in the throat area (if it becomes too large, it can be removed surgically, but such operations are rare).

The consequences of a pituitary tumor can include weight loss, weakened immunity, increased thirst and frequent urination, long (and often curly) hair that does not shed even in summer – in other words, Itsenko-Cushing’s disease.

While both types of tumors can eventually progress to life-threatening levels (and pituitary tumors are considered inoperable), the good news is that many horses live normally for many years after the onset of symptoms. Proper care, such as shaving a hairy horse with Cushing’s disease and giving oral medication, can help treat symptoms and restore an old horse to an active and normal life for some time. Horses with a thyroid tumor causing hypothyroidism generally respond well to powdered thyroxine, while horses with pituitary problems respond well to cyproheptadine or pergolide.

In general, it is safe to assume that most horses over 20 years of age have some kind of tumor. For example, lipomas in the abdomen, which are not cancerous but can cause problems because they tend to grow on thin stalks that can wrap around the intestinal lobe and obstruct blood flow and food passage (they can sometimes be removed laparoscopically) .

The abdomen can also be the site of widespread cancers such as lymphosarcoma. A fairly common problem isskin elanoma, especially in gray (and sometimes piebald) horses. It is estimated that almost 80% of gray horses over the age of 15 suffer from melanoma. As a rule, they are benign, but, unfortunately, they can grow and degenerate into malignant ones. If the melanoma spreads into the abdomen (as often happens) the horse may begin to lose weight and condition, become weak and suffer from fluid accumulation in the abdomen. Large growths can disrupt blood supply, innervation, and the functioning of the gastrointestinal tract.

Kidney and liver problems

Next on the list of problems are age-related diseases of the liver and kidneys. Although they do not occur as often in horses as in aging dogs and cats, once they start, they become progressive and irreversible. Their development can be slowed down, and the symptoms can be managed to some extent by changing the diet.

Liver failure is characterized by weight loss, lethargy, jaundice (yellowing of the mucous membranes and whites of the eyes), loss of appetite, and intolerance to fat and protein in the diet. If the pain becomes too intense, it can cause behavioral changes. Affected horses become irritable and can sometimes be observed to spin aimlessly or stand with their forehead against the wall.

Since vitamins B and C are synthesized in the liver, sick horses tend to be deficient in these vitamins (they can be given orally). A horse with a diseased liver needs a high sugar diet to maintain normal blood glucose levels, so it needs to be switched to a diet high in carbohydrates and low in protein and fat.

Weight loss and anorexia can result from reduced kidney function, and these problems can be fatal. Horses are unique in that they get rid of excess calcium by excreting it in the urine rather than the faeces. But when the kidneys are not functioning normally, calcium (as calcium oxalate) can accumulate in the tissues of the kidneys, urethra, or bladder as “stones” rather than being excreted. These stones can be extremely painful and often interfere with normal urinary function. Stones in the bladder or urethra can sometimes be removed surgically, but those in the kidneys are inoperable. When a horse suffers from kidney failure, a fatal increase in calcium levels in the blood is possible.

Reproductive function

reproductive function tends to gradually decrease with age. Many horses remain fertile well into their 20s, but ultimately the decline in sex hormone synthesis compromises reproductive performance, leading to low sperm counts in stallions and an inability to “hunt” or conceive in mares.

Older geldings sometimes develop infections and swellings in the scrotum that make it difficult for them to urinate. Regular washing of the scrotum with antibacterial soap will help reduce the number of pathogenic bacteria and keep swelling to a minimum.

hoof horn

The hoof horn tends to grow at a normal rate even into old age. So if an older horse works less (or doesn’t work at all), he may grind down the growing hoof horn less vigorously and needs to be trimmed more frequently than when he was young. Therefore, if your old horse does not walk on hard ground and does not carry a heavy load, it is better to unchain it and let it go for a walk “barefoot”.

Терморегуляция

It has been found that in older horses, thermoregulation (maintaining core body temperature) tends to worse than their younger counterparts. Extreme heat or cold for their body is a serious stress. Thus, in summer it is important to shelter an old horse from the sun or rain under a canopy (and perhaps put a fan in the stable aisle), and in winter to put a warm blanket on him and provide shelter to protect him from cold and strong winds.

Older horses may also need more calories to maintain their body temperature in freezing cold. And to prevent dehydration, it is better to take several times a day. give them warm water to drink.

Aging and athletic ability

One glance at the composition of horses competing at the Olympic Games will be enough to understand: the peak of sports form can be at five, and at eight, and even at 10 years old. Young horses create a high level of competition. However, Lisa Jacquin’s, with her 20 year old For the Moment, is showing an astonishing show jumping record while still facing strong international competition. A significant number of horses remain active and useful well into their 20s and even into their 30s, although for most the level of intensity of exercise gradually decreases.

Since muscle mass decreases with age, and tendons and ligaments lose elasticity, it is believed that the first horse loses speed, then agility, strength, and finally endurance. If so, it would be a good idea to adapt your needs to your horse’s changing athletic ability. Your jumping horse, for example, will no longer be able to maintain the speed needed to move quickly between obstacles in competition, but it can be used in sports games. Even later, it may continue to be useful as a school horse, for example for training young lunging riders.

If your horse is still healthy, it’s important to keep working (to the best of your ability). This will maintain his condition, develop his joints. In addition, work makes most horses happier. As Eleanor Kellon, VMD, writes in her book The Older Horse: “If you want a horse to stay active, Rule #1 is to never take it completely off the load. That means avoid long downtime.” Sedentary housing is not recommended for healthy older horses, she notes in her book, and even temporary downtime can lead to a significant loss of condition. An older horse that is out of shape is at an increased risk of injury.

In a study published in the December 1997 issue of the American Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Malinowski and Kenneth Harrington McKeever, PhD, measured the performance of young and old mares. They did this with a test on a treadmill raised at a 6-degree angle. Measurements of maximal oxygen uptake, blood lactate and hematocrit were analyzed and compared for young (mean age about five years old) and old (mean age about 22 years old, which is approximately 60-78 years old in human terms) mares. It was concluded that older mares have a significant (24%) reduction in maximal aerobic capacity. But some of the difference may be due to untrained older horses, says Malinowski. The results are consistent with data from a study of declining cardiovascular function in the elderly – the force of maximum heart contractions in older horses also gradually decreases. “Compared to other species, older horses still have amazing aerobic capacity,” notes Malinowski.

In the discussion part of the article, the authors Malinowski and McKeever noted that a number of questions about the athletic abilities of older horses still remain unanswered. For example: at what age does the aerobic capacity of horses begin to decline? (In humans, noticeable changes appear between 40 and 50 years, but no one has yet figured out this period for horses). Another burning question is: what amount of exercise will maximize the cardiovascular and aerobic capacity of an old horse without overworking and without risk of injury? “The ultimate goal of all these studies,” the authors note, “will be to determine the level of adequate exercise to meet the needs of older horse athletes. This data is necessary as many horse owners continue to train their older animals with techniques that are suitable for a young animal but may not be suitable for older horses.”

When is it time to retire an old horse? “There is no retirement age,” says Ralston, who is also an equine nutrition expert and contributor to equine aging research at Rutgers. “Don’t fix what isn’t broken!” she says. “The worst thing you can do is retire an old horse just because it has reached a certain age.” As long as your horse is generally healthy, adequate exercise will be good for his mind and body. If he is lame, has breathing problems (such as shortness of breath), or otherwise cannot enjoy active movement, it is probably best to retire him. However, keep in mind that retirement does not mean oblivion. Horses will need meticulous care to maintain their quality of life.

Features of the content

Older horses require higher maintenance costs than their younger counterparts. Geriatric horses are prone to disease and infection because their immune system is no longer as efficient as it used to be, so it is important to watch closely for signs of infectious disease. Vaccinations must be carefully planned. Your vaccination plan should include regular flu shots (eg new intranasal vaccines) and equine herpes virus shots, even if you haven’t had them before. Just like the elderly, older horses also need help to ward off infection.

It is also vital to maintain a regular deworming schedule and inspect your teeth at least once every six months for signs of decay or excessive wear. Also, if you notice that an older horse is not eating well and/or is depressed, it’s worth getting a blood test done to look for early signs of liver or kidney dysfunction, or pituitary or thyroid problems.

Ensuring proper nutrition, namely chewable food, is also a key part of caring for an older horse. Older horses are at increased risk of both esophageal obstruction and colic because they chew and digest food less efficiently than younger horses.

Difficult-to-treat chronic diarrhea is the result of a fragile population of intestinal microflora and a decrease in digestive enzymes. Therefore, stress, feed changes, or intestinal infections can cause diarrhea, and some horses may need electrolytes to rehydrate. Probiotics can be of great benefit to older horses. Sometimes older horses try to colonize the intestines with microorganisms, like foals, with the help of coprophagy (eating their own and other people’s manure).

Sensible management also includes protecting your older horse from unnecessary stress. For example, you should not let her go to pasture with violent young animals, games and rivalry with which will squeeze all the juice out of her. The horse will be happier in the field with his peers. An older horse tends to be less aggressive, and in a group feeding situation, younger horses may drive it away from food. So she doesn’t have to fight for her calories, lit is better to provide her with a stall or a separate corral in which you can eat in peace. .

Karen Briggs; translation by V.N. Kuzmina