Former “horses”: what to look for when buying?

Former “horses”: what to look for when buying?

Former racehorse: huge heart, hard work, athleticism, amazing sensitivity… and possibly a lot of physical problems. Are you able to identify the problems so common with these superb athletes? A sports career can seriously affect the body, which every serious athlete can confirm. Injuries and injuries will appear throughout a sports career, regardless of its success. They are the inevitable consequences of the work of the body on the verge of its speed, strength capabilities and overall endurance. At times, the body simply cannot withstand the pressure … And we are not even talking about falls and collisions that occur during competitions. These statements remain true for high-level athletes, and for those who are just approaching success, and for racehorses, and for Olympic athletes.

Former race horse injuries

A number of factors influence the severity of physical injury:

1) applied training methods;

2) the speed with which the training began and advanced (forcing);

3) the athletic qualities of the organism of a particular horse – the structure, maturity and genuine athleticism, not amenable to quantitative descriptions;

4) treatment received and time allowed for recovery from injuries, assuming that all injuries received were diagnosed (not all injuries are obvious);

5) requirements placed on the horse in terms of the number of races and the recovery time between them,

6) duration of racing career;

7) the mental and emotional ability of the horse to cope with physical problems (varies considerably).

As with any sport, there are things in horse racing that do well and things that don’t. Training can be literate and illiterate, rightly and wrongly assessed, as in the rest of the equestrian world.

A number of Thoroughbred horses leave the racing world in good condition and continue their sporting careers in top competitions. For many, minor issues are identified and rehabilitated, making the horse fit for a successful career with low health requirements. Often these horses become hobbies whose whole life consists of one long horseback ride.

Unfortunately, many Thoroughbred horses with moderate health problems end up with owners who have no idea that their horse has problems.

What should I look for when buying a former racehorse?

Working with clients, I see a lot of problems coming up again and again with former racehorses. I also see many owners who at one time had no idea who they were acquiring.

Despite good care and attention, the horse shows pain or discomfort, and the owner suddenly realizes that (a) his horse will not be able to carry the loads that he expected, and (b) the cost of treating the horse can significantly exceed the cost of the horse itself when buying .

The situation is sad. I believe that when looking at a former racehorse that has already gone through a couple of non-racing owners, you may run into problems much more serious than those listed here. The best solution would be to invite a veterinarian, but before that, just go through the list below …

Major Issues Affecting the Horse’s Ability to Exercise in Former Racehorses

Of course, not all health problems are reasons to refuse a purchase. The horse may well have a couple of problems, but still remain completely functional (however, if you take the horse directly from the race, a number of rehabilitation procedures are necessary). Your buying decision will depend on:

- the number of problems you were able to identify;

- the severity of these problems;

- what has already been done to help the horse recover;

- how much the problems will affect the way you planned to use the horse;

- whether you are able to provide the horse with the necessary rehabilitation and support in the treatment of identified problems or pay for the services of a specialist who can do this.

The list below is by no means exhaustive (problems are diverse, diverse and their combinations, in addition, some problems can provoke others, secondary ones). I will also not delve into the field of horse hoof care, since this topic is very important and worthy of a separate article.

Below I will talk about problems that you can identify quickly and relatively easily. Most of them are visible visually. You can enlist the help of a more qualified person or (before making a decision) have a complete veterinary examination. It’s best to do both.

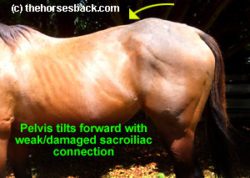

1. Sacroiliac injury – determining not the presence, but the severity of the injury (mild, severe or extremely serious).

Sacroiliac injury is the number one problem as every former racehorse has ligament damage in this area. Depending on the severity of the injury, there may be healed lesions or trauma resulting from prolonged weakness.

Often in case of severe ligament injury there will be further visible changes in the pelvic area, the horse will be asymmetrical. A severe injury can usually rule out a future racing career, while a moderate injury may require a period of rehabilitation to strengthen the back and prepare the horse for further work. Minor damage after healing of the ligaments is not a problem.

The pelvis tilts forward due to a weak/damaged sacroiliac joint.

Rice. 1. The difference in height is obvious, and this problem is not the only one.

Should be ventilated: asymmetry of the sacral tubercle of the pelvic bone (two bone processes in the region of the croup). The horse can walk by raising one side of the pelvis higher than the other. The development of the muscles of the croup can be uneven. These horses are almost always reluctant to raise their hindquarters – they quickly raise the leg high enough and then lower it back into place. The horse may also struggle to stand up straight (in a regular rectangle), instead placing the hind feet close together, with the hoof of one foot may be turned outward. Always check for problems with the lumbar spine (see point 3 below).

2. The pelvis can be seen as the center of the horse.

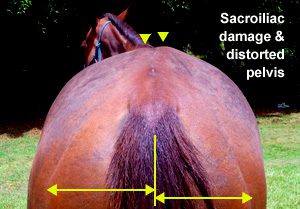

Along with sacroiliac problems, former racehorses may have other structural damage to the pelvic region. Some of us can see them, some of us can’t. The most important thing is to check the overall symmetry of the pelvic bones. You need to check not only the rotation of the pelvis (moving one side up or forward), but also the curvature.

Рis. 2. Sacroiliac injury and twisted pelvis.

Fig 3. Damage to the pelvic bones of the horse.

In horses that have experienced severe trauma at a young age, the pubic symphysis (the lower cartilaginous articulation between parts of the pelvic bone, right between the limbs) is not formed correctly. Due to pressure or stress, the pelvis may expand, and this part of the pelvis never connects.

What problems does it cause? Severe damage to the pelvis prevents the horse from working equally well in both directions and may prevent him from cantering off one leg. These horses are at an increased risk of having occult stress fractures – fractures in the form of a crack in the bone that can worsen with further falls or injuries throughout life.

It is necessary to make sure that all the pelvic “bone landmarks” are present – maklok, ischial tuberosity, croup. Occasionally, fractures result in a “knocked-out maklok”, one of the sacral tuberosities of the pelvic bone may be omitted due to a fracture of the wing of the pelvic bone.

Should be ventilated: symmetry of the pelvis, determining the location of “bone landmarks”. If you know the horse and it’s not dangerous, stand on a box a few feet away and look down at the horse’s back in a square stance (if the horse can take that position). Otherwise, raise your mobile phone above your head and take a frontal photo of your back, make sure the photo is clearly in focus. In any case, when conducting an inspection, do not forget about your own safety!

3. Direction to all four cardinal points … lumbar spine

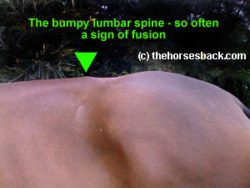

If you find problems in the sacroiliac or pelvic areas, you are likely to find problems in the lumbar spine as well. The lack of lateral symmetry of the pelvis most likely leads to displacement of the lumbar spine. Problems of the lumbar spine can also occur independently of other disorders.

In the case of a long-term displacement of the lumbar spine, adhesion of the vertebrae usually occurs, and / or dorsal overlapping of bone fragments one on the other (that part of the spine that you can feel). Areas of adhesion are painful to the horse during the process and do not bring visible pain when the process is completed. But if the adhesion breaks, it can again cause severe pain. Many horses compete successfully with multiple adhesions, but if the processes are severe, vertical and lateral flexion problems arise.

Rice. 4. The arched lumbar spine often has adhesions.

Rice. 5. Tuberculous lumbar spine is often a sign of adhesions.

Should be ventilated: check the lumbar spine with your hand for “bumps and tumors” that may indicate adhesions. When viewed from the side, evaluate whether the lumbar spine stands out, does the back look humpbacked (cyprinoid)? Usually in this condition, if the problem is prolonged, the pelvis will tilt back. If the pelvis is tilted forward (you will find an elongated depression in front of the croup), this will mean that the sacro-lumbar gap is greater than normal.

4. “Knee Bones: Take a bag of knuckles and shake well.” — as Tom Iwers, one of the first experts in the field of equestrian sports medicine and racehorse trainer, put it.

Horse knee joints are fragile and complex structures made up of numerous small bones that form the skeleton of the wrist and carry a lot of stress during a racing career.

Problems such as bone fractures with soft tissue injury and bone chips in the bones of the wrist are due to overextension (when the joint flexes slightly in the opposite direction) at high speed or from a constant load on the same bend. In addition, there are also complex fractures, when the bones of the wrist break more than two segments.

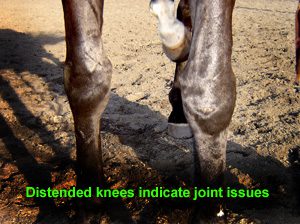

Rice. 6. Looseness of the knee joints indicate their damage.

Should be ventilated: swelling around the joint, especially in the front of it, due to previous swelling of the joint capsule. Old bone fragments and soft tissue fractures (healed) can be associated with long-term joint damage, which can later provoke osteoarthritis (carpitis – inflammation of the carpal joint).

5. Stress due to metatarsal injury

Former racehorses may have suffered metatarsal injuries early in their careers. For example, stress on the periosteum (the soft tissue that surrounds the bone) caused by a strong blow causes the body to respond with excess calcium deposits to strengthen the bone. The bone is restored, but in all parts that have undergone remodeling, it will be weak.

In severe cases, an undiagnosed stress fracture may occur, which, under high loads in subsequent periods, can lead to catastrophic consequences.

Rice. 7. An x-ray of another horse shows the nature of the problem.

Should be ventilated: flexion of the anterior metatarsus, which in the presence of severe remodeling indicates that the problem was severe.

6. Tendons, tendons and again damaged tendons

Flexor tendon injuries are extremely common in racehorses. The tendons of the deep digital flexor and the superficial digital flexor are most commonly affected. These can be relatively minor injuries that heal quite well, or more serious tears that put an end to the horse’s racing career. Due to tendon weakness, there is always a risk of re-injury. In some cases, a second rupture can be catastrophic. Often a lot depends on the quality of the treatment and the amount of rest and restorative therapy before returning the horse to work.

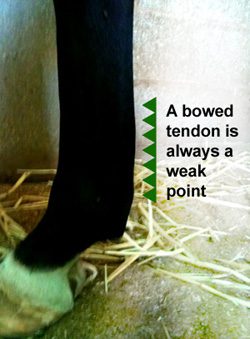

Rice. 8. A bulging tendon is always a weak point.

Should be ventilated: A thickening in the area of the tendon is indicative of an old injury that has healed, while a kink along the length of the tendon is the classic ‘bowed tendon’, a sign of a much more serious injury.

7 Small But Vital: Femur Fractures

Vulnerability of the fetlock occurs due to overextension of the limb, when the back of the fetlock is lowered too close to the ground, when the weight of the horse at high speed is transferred to the forelimb. An extremely strong effect is exerted on the fetlock joint and the fetlock bone when the horse lowers the front leg to the ground.

Poor hoof care in the form of “low heel, long toe” imbalance also plays a major role.

In the case of a fracture, its type and location are of great importance.

Injury to the sesamoid bone (two small bones behind the tarsal bone) can be a serious problem affecting the suspensory ligament.

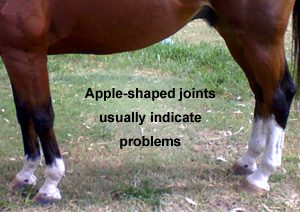

Rice. 9. Apple-shaped joints are usually an indicator of problems.

Should be ventilated: sesamoid fractures present as “over-rounded” or “apple-shaped” fetlocks when swelling from an old injury has destroyed the joint capsule and/or excess calcium deposits have formed around the injured joint. Are the fetlocks of the forelimbs the same size and shape? If one joint is larger than the other and more rounded, or if the tendon on the back of the limb is more dense to the touch, with swelling above the back of the joint, then you should think about it.

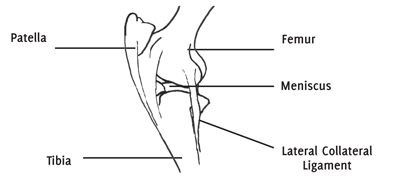

8. The knee joint almost always suffers.

Former racehorses often have knee problems. Keep in mind that if there are problems with the hindquarters (whole hindquarters or sacrum, plus hindquarters), the knees are likely to be involved as well. Impairments include any imbalance in the pelvis that results in an uneven distribution of weight on the hind limbs, not to mention forces that lead to unilateral flexion when running. In addition, there are dislocations with displacement, which can occur as a result of a collision or when working on poor ground. There are so many tendons around the complex double joint that it is not so difficult to damage it.

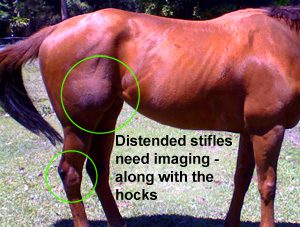

Rice. 10. Loose knee joints need to be examined along with the knee tendons.

Should be ventilated: a constant clicking sound made when the horse begins to move the hind leg forward. This is a pinching of the patella, which can occur due to a violation of the transverse balance (causing displacement of the femoro-patellar joint). Other signs are determined visually: stretching (swelling) of the joint can be seen from the side or when viewed from front to back in the direction of the tail, depending on which part of the joint is affected (femoro-patellar or femoro-tibial).

Rice. 11. Patella – patellar cup; Femur – femur; Meniscus – meniscus; Lateral Collateral Ligament – Lateral (external) collateral (lateral) ligament of the knee joint; Tibia – tibia.

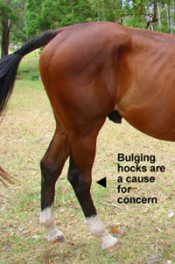

9. Talk about the hindquarters: hocks are also vulnerable

The hocks bear the main stress load due to the fact that they are involved in providing the driving force during the canter. As the main articulation joints, they are central when jumping out of the starting gate/hurdles when they carry almost all of the horse’s body weight. During cantering, the joints must change state from contraction to absorb shock, stiffness to generate power, to full extension to release power to propel the horse forward. Joints are often subjected to uneven compressive stress. This is how unexpected sprains and injuries occur. Good a well-formed hock joint can handle such loads relatively well, but an overly straight joint, the “cow joint”, is less able to carry a serious load. Usually, degenerative joint disease develops in the lower bones of the joint, especially on the inside, which racehorses enter the turn.

Rice. 12. Swollen hocks are cause for concern.

You should check: inspect the surface of the joint for swelling. Check for knee bulges, which are specific fluid-filled bumps on the front of the joint that are indicative of an underlying problem. Bone outgrowths are their bone equivalents, which are hard bumps that lie below the surface of the joint. They say that there is a persistent degenerative joint disease (arthritis). Also listen for a creaking sound or crackling sound when the hindquarter is lifted.

10. Collision and shoulder strike

Race horses may be subject to uneven stress at the base of the neck above the shoulder. This can happen when horses collide with each other or with a fence, during a fall, or as a result of everyday situations (for example, due to a strong blow to the stall door). One possible outcome would be damage to the supraspinous nerve that runs along the facial surface of the scapula. Damage can lead to loss of muscle mass or even paralysis of the muscles above the shoulder blade, which is a serious problem as these muscles stabilize the shoulder joint. This condition is known as shoulder muscle atrophy (‘sweeney’). Mild cases are usually cured, but more severe cases can lead to permanent loss of muscle tissue. Horse with not fully functional shoulder and a shortened gait is not suitable for sports that place serious demands on the condition of the horse.

Rice. 13. Suprasculptural nerve injury leads to loss of muscle mass.

You should check: lack of muscle mass over the shoulder blade. These are not just tense muscles – the crest of the scapula will stand out visually and be easily determined by touch.

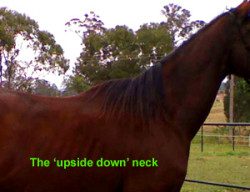

That’s not all… there’s always more

In an article like this one, it’s hard to put an end to it. But I hope that it will be of help to you in case you need to assess the condition of the horse. Many of the problems listed above can be encountered when buying any horse, however, anyone who regularly works with former racehorses will recognizeаThere are whole complexes of problems that are usually associated with this sport.

Rice. 14. “Inverted” neck.

I didn’t consider: common problems with the neck (calcification of the upper part of the nuchal ligament, deformity of the atlas and atlantooccipital joint, etc.), occult stress fractures (the most common fractures are the radius and tibia, scapula, ribs and other bones), abnormalities in the C6- T4 (C6 – ventral cutaneous branch of the cervical spinal nerve 6 – T4 – lateral cutaneous branch of the thoracic spinal nerve 4) and a large number of other cases, but it is difficult for the layman to identify the relevant problems.

In conclusion, I will talk about two horses that have raced in Australia, where it is customary to train horses on a circle, where they take part in most of the races. In New South Wales, horses gallop clockwise (red), while in Victoria (bay) they gallop counterclockwise. The sight of their crooked backs tells us a lot…

Rice. 15. Left: Horse in training and racing, clockwise. Damage to the sacral joint on the right, bending of the spine to the left.

Right: a horse being trained and racing counterclockwise. Damage to the sacral joint on the left, bending of the spine to the right.

Jane Clozier (source); translation by Dina Maximova.

Here you can read stories about horses translated by Dina.