Andrew McLean: on learning theory and biomechanics

Andrew McLean: on learning theory and biomechanics

Andrew McLean is not only an athlete and a rider. He is an eminent behavioral scientist. Of particular interest are his views on the theory of horse training. Andrew has a special understanding of progress in training. There are so many “experts” in the horse world who, having picked up a piece of some worthy theory, spend the rest of their lives wandering around it without turning a single step. Andrew McLean’s position is based on a simple idea – the theory of horse training should be formed in accordance with the principles of a scientific approach, training programs should be based on scientific data, and not superstitions passed down from generation to generation.

Surprisingly, despite the fact that many areas of animal learning have been thoroughly studied (highly effective training methods have been identified), horse training has remained largely intact in terms of its rationality, presenting a rich field for all sorts of fakes and fraud.

As a behaviorist, Andrew has been able to link his vast knowledge of how horses process, respond and learn to cutting-edge research on how their bodies can and should move and how this translates into learning. The horse’s body has become another learning parameter.

One of the pioneers in this field was Professor Hilary Clayton. She was able to do a great job in the field of studying the biomechanics of the horse at the Ann MacPhail Center, using modern technologies to reveal exactly how the horse feels the effects of the rider.

Next, we pass the floor to Andrew…

“When you look at the work of the horseman’s seat (what we did at the Center) and you see, what seat really does during transitions and half-halts, then you understand that the horse is not entirely clear what is required of him, in contrast to, say, the demands given by the reins and legs.

“A saddle is put on the horse, which distributes the weight of the rider. The sitting bones do not rest against the horse’s back (if they did, the horse would be in pain). Also under the saddle are saddle pads and pads, which additionally distribute the pressure. It turns out that if you want to give clear, uniform, constant commands with your seat, then you will have to work very (!) Accurately and put the saddle on the horse every time in the same way as the previous one. And even so, we must remember that the horse does not hear the seat as clearly as such simple controls as the reins, because there are so many sensory receptors in the mouth.”

Andrew sees a gap between what riders and coaches think they think they are doing and what they actually do.

“Riders tell me, ‘I only stop the horse with the seat.’ But I say, “No, you don’t. If you let the horse go forward with the rein, he won’t stop just with the seat. I’ve worked with western trainers in America and they’ve shown me horses that do stop just from seat pressure, but that’s because they usually associate seat action with serious mouthpiece action in the early stages of training. The reason for even a slight impact speaks volumes, while the seat has a lot of “shouting”, especially on lateral movements.

“The seat is a very important control tool, but, in fact, it is an “accessory” for our reins and legs. Too much emphasis on the work of the seat, as it were, suggests that work on the influence of the reins is not taken into account. Few horses stop, slow down, rein back or shorten smoothly and immediately from a light rein, staying in line and not lifting their head or shortening their neck. We’re talking contact issues, we’re talking foot to hand, but we’re not really teaching the horse. what the hand does. The seat and half halts can only work correctly if the horse understands the reins correctly. Contact problems are related to stopping problems and are usually neurotic expressions of the latter. They also tend to be associated with problems with the front, but not only.

“Stop, Forward and Turn are A, B and C. There are coaches who understand this. For example, Kira Kirkund, Anki (if you do not take into account her rollkur). These trainers state that you should not push the horse to transition down, that ascending transitions come from the leg and downward transitions from the hand. If the transition is made in one step, then the butt is brought up and connected.

“More and more people are looking for objective explanations for why horses do things the way they do. The big problem is that even though riders are getting better and better marks in competition, horse training is still in the stone age! Riders use knowledge passed down from generation to generation and there are so many different systems, attitudes and methodologies… I am convinced that in every case success is due to the fact that riders (in most cases unconsciously) use what we call “theory learning”. Learning theory informs about the best and worst learning systems, what is good and bad about them, and how learning can be improved and made more effective.”

“It is remarkable, however, that the level of awareness is rising. The path will be long, but it has begun. The systematics of learning theory is only sixty years old, while riding has thousands of years of history. It will be difficult for riders and trainers to master the learning theory, but it is necessary for the welfare of the horses. Moreover, when people are fully awareаrealize their potential, this will drastically increase their performance in sports.”

“If someone tells me that he trained a bird to sit on his hand, I will ask him to let go of his wings – I want to make sure that he does this on his own. The same is true in dressage.

I guess part of the problem is the modern German approach, which I don’t like. I have traveled with trainings and taught in nine different countries of the world, and the picture is the same everywhere. Germany is a leader in dressage, which is addressed in most other countries, and it would be great if it provided a uniform training system focused on the welfare of the horse. I am a big fan of the late Rainer Klimke, I admire Klaus Balkenhol and Hubertus Schmidt. But there is a new German style of high pressure, and it is too heavy for the horses. This is especially noticeable in the young horse classes. With this style of training, instead of developing the physique, the frame closes, the neck and poll are clamped, the horse is tense, moving in a hurry. This misleads us, we consider it dressage and the crowd applauds such a performance. The Dutch rollkur technique is also hard on horses – they experience constant pressure from the mouthpiece and, even worse, simultaneous pressure from the mouthpiece and legs. Although the FEI believes that some riders may appear to be better at using rollkur than others, it is not uncommon to see overbending with simultaneous leg and rein pressure.

I think a test of the horse’s self-carrying ability is necessary in any training system – does the horse maintain rhythm, straightness and frame when you release the reins?

“Training methods where opposing pressures, such as the reins and legs, are used at the same time are called “overlapping”. When overlapping, the animal receives two powerful signals at once, most often opposite to each other. Even if the signals are not opposite, the horse will see that one rider signal is more “bright” than another, more “painful”. That is what she will react to. A weaker signal will eventually be ignored.”

“Overlapping, as a process, has both good and bad aspects. I will first explain how this process can be a useful tool for eradicating unwanted responses, and then it will be easier to see why it is not possible to simultaneously send signals that require two opposite responses under the saddle, as most riders do.

If you look at the problems associated with dangerous behavior in the hands (the horse does not want to be cut, he does not respond well to tightening the girth, you can’t inject her, etc.), you will see that all of them are associated with fear, can be blocked and brought under control.”

«Starting from the lowest threshold of fear, when the horse gently confronts the object of his fear, you simply override his reactions with clear responses, prompting the horse to step back and forth in his hands, maintaining a constant distance from the feared object. You ask the horse to step back and step forward, making sure to build up and release pressure when the horse responds correctly. When the horse begins to respond more easily to signals, he simultaneously loses his fear of a terrible object. You repeat by moving closer to the scary object or bringing it closer while still stepping back and forth. Surprisingly, not only do horses begin to become distracted from what they are afraid of, but the fear response begins to weaken permanently: this is a long-term consequence of training. After a series of repetitions, the problem goes away, the horse is no longer afraid of the syringe or anything else.

“An essential first step in this process is to establish clear and easy responses to very simple controls from the ground – in the case above, just a pretext. When you first teach a horse to step forward, you must increase the pressure to get him to step forward, you must repeat steps back and forth using only light signals. You should not take steps back and forth yourself – this will be a clue for the horse. Any cues before the horse has responded will cause the horse to anticipate rein action based on your legs. So you just have to move your hand back and forth, you can use a lead snaffle and very quickly the horse will go forward and back at the slightest signal. If you notice that the horse is not backing or walking forward because his attention is now on the clipper, you must increase the pressure to get your way. Basically the horse is saying “I can’t step back and forth because I’m focused on the car…” Then you bring the car closer again – so it’s a pretty quick process.

“I’ve done this at several veterinary conferences with horses that don’t like injections, and every time a horse was brought to me that wouldn’t let itself be injected, I took away its fear of injections. I have taught many veterinarians how to do this. With a clipper, things are similar – soon you drop the lead and begin to cut your horse. We demonstrated this at the AVA Conference held at our AVA Center. In a very short time – perhaps as little as three repetitions – the animal was completely accustomed to the clipper and felt comfortable during the haircut, sometimes everything happened even faster.

“Similar overlapping techniques are used in human psychotherapy for trauma. It’s called strength therapy, and its practitioners say it’s one of the most powerful treatments.”

“The overlap factor makes it clear to us that animals like horses and probably all of us can only respond effectively to one signal at a time. The weaker signal is ignored.”

“If you accept this truth, you can see that much of what goes on in modern horse training is an unintended overlap—one signal overlaps with another. When horses become confused or panicked, they are expressing the overlap of your controls with another stimulus.

It is much more useful to interpret behavior problems as a “signal that didn’t work.” A cat in the bushes blocked the rider’s signal. Thus, many modern training systems put us in an overlapping mode where the rider uses the reins with the leg most of the time. Even modern riding literature shows overlap. The German training manual instructs never to use a legless rein and this has its roots in the work of Steinbrecht. I think Steinbrecht was wrong. The simultaneous use of reins and legs has a long history: Xenophon recommended doing this to make the horse more impulsive.

“It is important to recognize that the main function of the reins is to slow the horse’s legs, and the muscles that slow down the movement and the muscles that accelerate it belong to completely different groups. When one muscle group is used, the other stabilizes the limbs, and that’s it. So if we signal leg acceleration and at the same time use the rein, we are simultaneously stimulating two opposing muscle groups. Once you’ve done that, you’ve gotten into an overlapping position, creating confusion and desensitizing the response – now you’re going to need stronger and stronger signals each time. As soon as the rein and leg give the horse a simultaneous signal, he tells us that he cannot do what is required. This can manifest itself in mild conflict behavior – tension, hyperactivity, tongue-flipping, restless mouth, biting on the reins, as well as serious conflict behavior – goats, candles, kicking, pulling, etc. All these manifestations are often attributed by trainers and riders to the characteristics of the horse’s personality. But it’s not about personality flaws – the horse tells you that you make mistakes and confuse him! Horses, unlike tennis rackets or motorcycles, are so easy to blame…”

“When you use the rein and leg at the same time, the horse, because his mouth is more sensitive, usually reacts more to the rein, his reaction is to slow down. Consequently, the rider then has to push the horse out to cancel the effect of the reins. In another case, the reins may act a little lighter, it will not work as a brake, but the horse running away will still be so embarrassed that he will begin to feel in danger and, thus, become less safe for the rider. She demonstrates her insecurity, becoming frightened of “horse-eaters”, even before harmless things, and can also show anxiety when she is alone.

The insecurity in riding and caring for horses is largely due to confusion in training. When the rider does not know how to ask, the horse cannot decipher his request (or the request is too similar to others, or the horse is physically unable to give an answer, or does not know the answer). A feeling of insecurity comes to her – her world is falling apart. On this basis, aggression can also arise, because people speak an incomprehensible language and make her nervous.”

Andrew is not a theorist out of practice. Let’s take a look at his success with solving the problems of the big prize horse, Lorenzo:

“I did some Belgium work with Wayne Channon, a member of the British dressage team. And this work can be a good example of overlap. Wayne is an excellent rider, but his wonderful horse, Lorenzo, had some issues. I spoke with Wayne about the principles of learning theory as we drove back from the Dressage Forum to his home in Flanders. Eit was a real flash course. Wayne is a highly educated person, nuclear physicist and entrepreneur. He was able to absorb a significant amount of the theoretical part of the training in the short amount of time we got to his house.”

“I checked Lorenzo in his hands to see how he moved forward and pulled back, turned and gave in, and some of his answers were not very good: he resisted and answered slowly. Dressage horses are rarely tested this way, so I wasn’t surprised, but reactions in the hands are a mirror of reactions under the saddle. It was necessary to help the horse cope with the passes – they were uneven, performing them, Lorenzo almost limped. I rode Lorenzo on horseback and found that without the spur, his reactions to stopping and moving forward were slow. I used the whip to propel him forward and he rebounded. I used the halt occasion and worked on some deeper transitions like trot-stop, halt-trot after three steps.

The whip and rein are the deepest, most powerful means of control – they are like a solid fence. They give the brightest signals and, when not in use, sensitize other controls (such as the leg). So when you want to fix a horse that is, for example, lazy, it will work much better if you make it start at the touch of the whip and maintain it for a while so that it goes from a stop to a walk and into a trot from two touches of the whip (lighter touches to transition to a walk, harder touches to a trot). ).

Wayne saw that his horse began to move differently. Lorenzo’s mouth calmed, settled contact. As soon as the wheels began to work on the stop and go, I moved on to turning and yielding – the main units of acceptance. I explained that my latest exposure was integrating learning theory with biomechanics.».

“It is necessary to analyze all locomotion directions, including forward, slow, backward, turn, and sideways. Every movement we make in dressage is a combination of these things. It is very important that the horse’s legs do everything right first, and then we can easily correct his head and neck if we need it.”

“Lorenzo had problems doing the half to the left, but he didn’t think of the half as a mixture of turning and leg yielding.

How do we practice turning left during a ride? The turn begins with the initial abduction (“opening”) of the front legs. It’s wrong to start a left turn with a “closing” right front foot, because that means you’re in trouble when you need things like pirouettes. Leg yielding should begin with adduction (“closing”) of the hind legs.”

“When I looked at Lorenzo’s half, I saw that his front leg in the suspension phase showed a short swing. His leg kick to the left was excellent. This told me that the right foreleg was stuck in the abduction phase of the stance—in other words, when it was on the ground and opened, it was losing strength.”

“We worked on a single turn step from a stop in response to the touch of the whip to the right shoulder. Lorenzo had problems, he tried to resist, leaned on the whip. But soon he nevertheless did everything right, because I rewarded his every slightest attempt. We repeated this until the step was large enough. Then we repeated it on the move – at a walk, then at a trot, just turning all over the place at the touch of the whip. When Lorenzo’s response stabilized, I added a rein signal, and now the rein urged Lorenzo to a wider and brighter step of the turn. We then moved on to attempting a leg yield, which soon worked, and then moved on to half passes, which worked almost immediately. Sometimes we had to use the whip to stimulate bоgreater reaction of the opening of the front legs. Wayne and Lorenzo had no more problems with taking».

«I really enjoy studying and working with biomechanical aspects like this one. Any movement can have biomechanical defects that can be corrected by a combination of operant conditioning and biomechanical knowledge.”

“Wayne was happy that the horse’s movements were smoother and the half stabilized, but he wasn’t sure about the idea of using the rein and leg separately on a dressage horse. I am convinced that this standard of simultaneous use of aids requires the impossible from the horse, and it slows him down.

I asked Wayne to give me an example of a move that can’t be trained using only one control at a time. And he said the most prominent example is the half-half: “I use the outside rein and the outside leg, the outside rein controls the bend and the outside front leg.” I replied, “But the steps do not occur at the same time. If you are using the controls to stimulate a particular step, then they are consistent. If we look at the principle that the horse walks on its own, once we have shown the angle of movement (which is why the shoulder in is the precursor in training), the horse only needs the signal from the outside leg, the bend and forehand are already moving in the right direction.” And Wayne agreed with me.

Top-level riders like him are certainly capable of signaling incredibly subtle and close in time and space. Dressage, as I always say, is your ability to put your horse’s feet where you need them at any given time. Usually, you will need only slightly adjust the position of the horse’s head and neck if you have perfect control over his legs. Before you worry about the position of the horse’s head, you must be able to slow, stop, shorten, rein and straighten the horse with the reins. The position of the head, neck and body of the horse flows into the correct general position.

“One of the problems in the dressage world is the conflicting ideas about how much contact a rider needs to have in their hands. We recognize that the rein is involved in the deceleration, then if you have “x” kilograms or grams of contact as you ride forward then the amount of weight you need for the deceleration effect must be more. And things get worse as you need more and more contact to get a slowdown response. For some horses, especially those of the more modern dressage type, certainly the more thoroughbreds, such as Trakens, Thoroughbreds or Spanish horses, the effect is disastrous. They cannot accept this contact – they start to have behavioral problems because they are forced to endure pain that they cannot cope with, they need easier contact! Not so high blooded breeds, especially those descended from draft breeds, usually seem less sensitive and can get used to pain/pressure more easily. They seem to be able to tolerate the confusion that comes from applying opposing pressures with less noticeable effects (I think the effects are still buried deep inside). But as more elegant and hotter horses tend to be used in big sports, we must know that because of their sensitivity we must be much more careful in contact.”

“Dressage should be a demonstration of optimal learning – horses should be trained to perform within their physical limits in response to the lightest of cues. It is wrong to preach strong continuous pressure, it should be outlawed. Judges must show courage and side with the horse first. They should immediately deduct marks if the horse looks like it is running away from under the rider, falling to the side, resisting the bit, losing the frame and changing head position, if the rider loosens the reins for at least a couple of steps to the point of sagging.

“If existing conditions persist, further deterioration in the mental state of the horses may occur. When animals lose control of their own lives, when pain is unpredictable and inevitable, animals, especially horses, seem to become immune to the pain of the snaffle and spur. I say “apparently” because on the outside they look calm, but on the inside they are dying. Gastric disorders (gastritis, colic, etc.) and immunological changes add to the general detachment and apathy that characterizes a horse in such an unavoidable situation. This condition is known as learned helplessness and was the subject of my presentation at the last World Dressage Forum.”

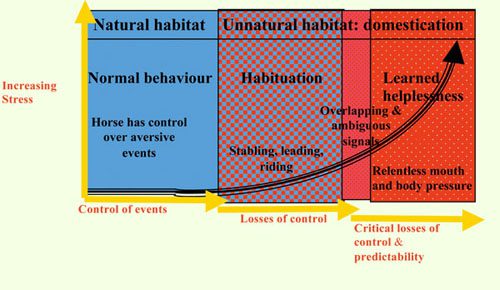

Up arrow: Increased stress. Arrows forward: Event control. Loss of control. Critical loss of control and predictability.

Column headings: Natural habitat. Unnatural Habitat: Domestication.

1 column: Normal behavior. The horse controls aversive events.

2 column: Addictive. Staying in the stable, walking, horseback riding. Overlapping and ambiguous signals.

3rd column: Learned helplessness. Relentless pressure on mouth and body.

“The model I have outlined for you came about as a result of a discussion about learned helplessness at the 2007 Michigan Riding Symposium. Note that the curve of learned helplessness rises as uncontrollability and unpredictability emerge as a result of relentless pressure on the horse’s mouth and body, and a tangle of overlapping and ambiguous control signals.”

“In the natural habitat, the horse is in control of aversive/unpleasant events – it can run away or fight back. In “home” conditions, when we stable, manage, ride horses, we can observe that it is possible to train horses to do things that might otherwise scare them, so the stress level is still low and tolerable. . I think this low stress level is negligible in the life of an animal. But when we start giving overlapping and ambiguous signals, or expecting two different responses from the same signal, then we are on the path to anxiety and learned helplessness.

For example, we use leg to yield, leg to canter, and leg to propel. Some riders tell me they use their leg to turn – how is the horse supposed to understand us, how is he supposed to decipher these complex demands? Many horses still endure this, but when we add incessant pressure on the flanks and mouth to the confusion, the situation gets worse. The horse is forcibly restrained. This is true in horses with high necks, and also in rollkur where the rein signals are anything but gentle. If a horse is kept under constant pressure, he starts to buck, kick, get confused, he may start to show conflict behavior, and then becomes a candidate for learned helplessness.

“The most important thing in training is light signals that do not offend or harm the horse. Light signals provide predictability. At an early stage of training, they tell the animal: “This pain precedes this” – so the horse soon learns to avoid pressure and pain, responding to light signals. Lightness is a win-win situation for horse and rider. It’s like when you can speak politely to someone and be sure that the conversation will not lead to violence.”

“That’s why the concept of the horse’s ability to carry itself, that the horse has to walk on its own, is so important. The concept is not new – it was one of the elements of the Bosch training scale. It is also supported in the German system, but how many horses carry themselves? When the answer to this question becomes positive, everyone will benefit – both horses and riders … ”

Andrew McLean (source); translation by Valeria Smirnova.