Additional controls – do you need them?

Additional controls – do you need them?

This article is about devices that are made and used to lower a horse’s head. All of them have the same function – they limit the height to which the horse can raise his head, and force the animal to solve the problem – how to cope with the pressure they create.

For my part, I am convinced that it is necessary to look for other methods of influence, not to achieve a mechanical lowering of the head into the desired position, but to stretch and lengthen the neck, which causes the horse to stretch and raise the back. This is what makes her “liberated” …

Devices affect only the front of the horse – the back can work as usual.

Devices can be defined as any piece of equipment worn on a horse, other than the usual saddle and bridle with a snaffle or headband with a mouthpiece, or as “tackle items that affect the horse mechanically”, as opposed to controls. I like the second definition better, although its boundaries are fuzzy. In some cases, something that is not included in the “composition” of a simple bridle and saddle may benefit the horse, but is not intended for the direct “use” of the rider, such as snaffle stabilizers (“bibs”), which prevent the snaffle ring from getting into the horse’s mouth when pulling gnawed in the mouth.

So, let’s look at the most common auxiliary controls.

Sliding reins (reins)

The most talked about aid used in dressage is the sliding reins. In German, they are called Schlaufzugel (loop reins) and, jokingly, Schlafzugel (sleeping reins). No other device is abused as often. Some riders, in principle, cannot imagine their work without them.

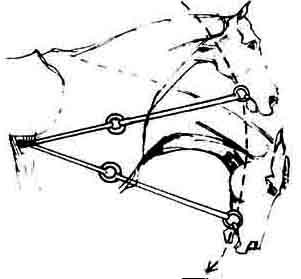

The pin is the simplest device. These are just two long reins that are attached at one end to the girth between the horse’s legs, or on the sides. From there they, passing through the rings of the snaffle on both sides, return to the hands of the rider. The fixed length between the girth, snaffle and arms prevents the horse from lifting its head or sticking its nose out further than the bridle will allow.

The sling is used for a variety of purposes. Many riders use it as a last resort in the fight against acceleration and overshoot. It is believed by some to help prevent mishaps at the beginning of a horse’s training in air changes. However, most riders use the tongue because they are unable to get contact from their horses, or in memory of the times when their horse ran with its head up due to lack of balance or other difficulties. Why do I find sheet piles unacceptable? Will explain…

Power and grip

The sliding function of the bridle and the fact that it is attached in two places (below and behind) opposite to the direction the horse wants to move its head (up and out) makes its action many times stronger than that of a simple rein. Working with a simple rein, the horse can raise his head, while the length of the rein from hand to mouth remains unchanged. To overcome the resistance of the horse, the rider must pull his head, lowering his hands down (see photo on the right). Without the necessary skills, he will not succeed. Thus, the tongue is an instrument of power, not of cooperation and trust. He will easily make an incredulous horse with back pain, racing with his neck and head up, obedient …

But what do sliding reins actually do? Are they good and safe?

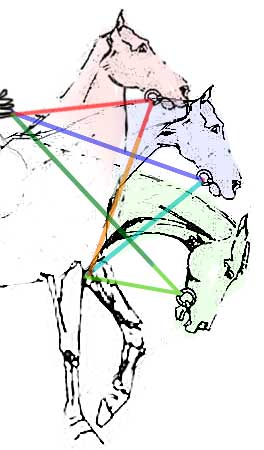

Head positions possible with a certain length of reins.

The active splint pulls the snaffle down and in, in a direction between the girth attachment and the rider’s arms. It becomes a trap for the horse. There is room to move inside the restraint, but not in the right direction – front-down-out, while the horse can twist his neck back (green position). She may also clench her neck and raise her head (red position) in an attempt to ease the action of the iron.

In order for the horse to relax the jaw and the back of the head and stretch the neck forward-down-outward as we would like, the rider needs to increase the length of the sliding reins, but bridlers usually do not do this, preferring to pull on themselves and shorten the frame. Problems also arise from the insensitive hands of the riders, who are reluctant to soften and give and rarely do it on time. It is difficult to release the sliding rein while maintaining contact with the mouth through the regular rein. At best, the horse is tucked in with a drawstring when it sticks out its nose, and dropped when it softens its jaw. But after all, one should strive to naturally relax the horse, and not fight it!

A horse tied with a string.

It is also undesirable to use a sheet as a safety net, since ideally it is necessary to be able to change the length of the horse’s neck and encourage him to periodically stretch forward-down-out during the entire training. A loose line that comes into play when the horse sticks out its nose, affects it and when it pulls forward-down-out. In such a situation, the rider should change the length of the line whenever he allows the horse to lower his head, shorten it by asking him to raise his head. Otherwise, the long sheet would not do any work!

Initiation of deflection

You will not be able to lower the head of the stargazer horse by pulling the reins down – it will resist. But she will also begin to struggle with the downward pressure of the tongue. The normal rein does not serve to lower the horse’s head. It is needed to relax her jaw and tongue so that the horse itself pulls its neck forward.

The vertebral column of a horse, bent due to a reflex awakened by the action of a sliding rein.

A tightened tongue has the same effect on the horse’s abdominal muscles as in rollkur – they contract, the nuchal ligament is tightened, and the topline is shortened. The bottom of the S-curve is pushed forward and you end up with a sagging horse. At the same time, the increased pressure on the tongue causes tightness in the jaw and occiput, which causes the same tension in the topline as when working with a raised head. Whether the horse raises its head itself or fights with the tongue – the effect will be the same, since it depends on the same reflex.

“Elastic bands”

The horse’s neck is broken at the third vertebra.

They have a mechanical effect and at the same time they cannot be adjusted directly during the ride. Elastic bands are attached to the girth and go through the snaffle rings up to the back of the head. This device does not go to the hands of the rider.

The rubber bands are elastic and therefore can invite the horse to contact. Their main disadvantage is that they are not adjustable by the rider – they cannot be softened and released to reward the horse or allow him to fully stretch. Rubber bands do not teach a horse anything other than lowering its head. Their use relieves the rider of the need to hold and manipulate the tongue. But the fact that the rubber bands have a mechanical effect and do nothing to help the rider “talk” to the horse speaks against them.

Too short rubber bands.

The elastic bands stretch and lengthen so that the horse can stretch forward-downward-outward, but only if they are not too short. However, if you adjust them loosely enough, they will not prevent a stubborn horse from shortening his neck and lifting it. In defense of the rubber bands, all I can say is that the horse can use them to calm the snaffle in the mouth if the rider has restless hands. The hard, steady pressure of the horse is more pleasant than jerking from sag to tension and back again. The horse can lower his head and lock the snaffle in his mouth using the elasticity of the rubber bands.

Side reins (interchanges)

Decoupling with rubber rings-shock absorbers.

In the Spanish School of Riding, interchanges are traditionally used when working on the lunge and on the reins. My opinion is that instead of longing the horse in the crossovers, provoking him to fight with them or move behind the vertical, hide from the snaffle or learn to hang on it so that it stops rattling on the teeth, it is better to spend time working on the reins or just by hand. Much more can be done by putting only a bridle on the horse and working with him in his hands on a line located at a distance of a meter from the wall of the arena, bending and working on stretching at the walk. Bending and shoulder-in at the walk are often more beneficial than trotting at crossovers.

Reversals only force the horse to turn its head inward.

Some riders claim that they can straighten the horse only by lunging in the crossovers. They shorten the inside halfway to get a curve in line with the path of the circle and then lunge the horse. But the reins cannot feel the horse’s straightness/curvature, cannot move on both sides of the horse with the horse’s legs, or soften to allow the horse to stretch. They can only fix the head. I have seen many horses after such work: they are twisted – overbent on the inside, with the shoulders dropped out, and their hips move along the inside track closer to the center than in front.

Do not fix the horse’s head! Shoulder in at the hands on the volt, then on the reins, and work your horseback on rhythm, relaxation, contact and schwung (impulse) before you start working on straightness. Straightness cannot be achieved by adjusting the straps, just as you cannot get a horse on the reins by forcefully lowering his head.

Reinings do not improve the horse’s stretching skills, but rather train him to hold a certain position of the neck and jaw and drop down the withers.

They fix the distance between the mouth and a point on the girth or edge. The horse can resist this in many ways – shortening the neck, twisting, etc. To force the horse to “get on the reins” using the reins, you need to be an expert in lunging – moving the horse forward and releasing pressure frequently so as not to provoke cramps caused by resistance. The horse should listen to you perfectly. So what’s the point of using junctions then? If the horse is well trained and you know how to manage it properly, then why not work it on the reins or under the saddle?

The horse in the photo is well trained. The junctions on it seem too short. On the step, she is bent and twisted. She arches her neck during the piaffe, but does not engage her hindquarters enough, her hind legs are raised higher than her forelegs, the reins are long enough (although I would like to see a longer neck). Yes, interchanges can be helpful during very short reprises in exercises that require a high degree of collection. But they can teach the horse to avoid contact by hiding behind the reins.

Rubber rings dangle up and down.

Using reins to shorten the horse is counterproductive – the horse will soon learn to strain against the action of the unyielding ropes attached to the reins.

The side reins also block the movement of the head and neck at the walk and canter, leaving the trot the only gait at which they can be used. During the trot, the rubber rings on the interchanges begin to rock them up and down, and they weigh much more than the reins. The only thing that helps the horse to evade this rather unpleasant influence on the rein is to lean hard on it.

Reinforcements block the stretch and encourage the horse to pull his head to his chest.

Problems also arise if the horse stumbles, loses balance, plays along on the lunge: the fixed leather tie hits the horse in the mouth with the same force with which he jerks his head. This traumatizes the horse’s mouth, making it less sensitive. The horse gradually becomes stiff.

Some people think that side work can teach the horse “correct contact”. If they mean that the rider must be able to hold the reins at a fixed length for a long time and that the horse must constantly adapt to it, then the reins can help. But if “correct contact” means to you that the horse is reaching for the reins, that the rider can adjust the length of the reins to influence the work of the horse’s hindquarters and back, to reward him, to allow him to stretch, to raise and lower his head, while maintaining the same pressure in occasion, then interchanges can teach the horse to ignore the rider’s hands, not to “mess around” with them.

The reins cannot properly position the nape of the horse. It is possible to make one halfway shorter than the other, but by lunging you will not be able to control the condition of the horse – whether it is bent at the shoulders, in the middle of the neck, or in the correct position.

The main problem with interchanges is the lack of control. You cannot control their length from the opposite end of the lunge, nor can you control the horse’s shoulder or bend. You cannot instantly soften or shorten them. If you can’t attach them to the primer, can’t find the lightest rubber rings, can’t loosen the decouplings long enough, and can’t ride neatly, then why do you need them?

Balancing rein (Todeman’s reins)

Todeman’s reins are semi-sliding reins that an unskilled rider can use without holding extra straps. They are attached to the girth, pass through the snaffle rings and are attached to the sides of the reins.

Some riders praise this device as being gentle on the horse. The reins only work until the horse has his head in the correct position, and then automatically loosens.

Todeman’s rein advocates don’t realize that they can’t get the horse’s head in the right position just by locking it in place with force. Proper head position is achieved by activating the hindquarters, resulting in a lift in the back and front, and a natural rounding of the neck!

Metal rings for fastening.

You can, of course, ask, why then at all a reason !? Why don’t riders ride without reins when it’s so damn simple? Because first “the back of the head should relax, and the position of the head under the influence of the snaffle on the jaw should approach the vertical.” This is the work of the hands if the horse is on the bit. Hands are asking: “Please relax your jaw, surrender the back of your head, stretch your neck, and I will give you a rein if you do this.”

The horse’s head must be free, and we must independently control it, reacting in time to everything that happens to it. We must feel the horse’s mouth, relax it if it is tight. And here we will be helped not by reins of a fixed length, each time pulling the horse’s head down, but by training.

Todeman’s reins add weight to the usual reins. They not only forcefully fix the position of the horse’s head and create tension in his neck, but also add discomfort to his mouth, constantly affecting the snaffle during movement.

Elastic adapters on the reins

These are reins with a ring at the end and an elastic section – an insert in the middle that allows them to stretch a little. Behind the insert is a leather section of the rein, so the stretch is limited (2-3 cm).

Such reins are used by riders who cannot create and maintain elastic, lively contact based on the horse’s feel and cushioning, whose hands are not independent of the horse’s movements and their own seat.

Unfortunately, they won’t help in the long run.

If you use these inserts, they will provide contact elasticity for you, and you will not correct and progress. Your hands will be restless – you will constantly pull on the reins, as the elastic inserts will automatically correct you. This way you will not learn to feel the soft chewing of the horse on the bit.

Chambon and Gogh

Gog looks like chambon, but additionally passes through the snaffle rings to the main belt.

Gogh and Chambon are much more complex than sheet pile and work through a system of blocks. They are designed to work on the lunge and encourage the horse to reach forward and down, but many people use these devices when working in the hands and on horseback. I do not understand why riders prefer to mask their inability with the action of “ropes”.

Chambon in action.

Chambon works satisfactorily when used for its intended purpose – on the lunge. This is the only device that allows the horse to fully stretch forward and down.

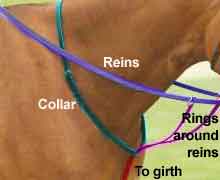

Chambon is very simple. You will need a lead to attach the main strap (blue) (if you don’t have one, use a saddle and girth). A short strap (green) is attached to the occipital strap of the bridle. At each end of the strap there is a ring (yellow) through which the cord (red) passes from the attachment to the snaffle.

Chambon parts.

Chambon is included in the work, as soon as the horse raises its head and puts out its nose, its cords are pulled. The distance to the raised head (nape) becomes longer than in the relaxed state, and the exposed nose also uses its part of the cord. The cord puts pressure on the mouth and also pushes down on the top strap. Any attempt to move the head in the right direction is instantly rewarded. If the nose goes back to the vertical, and especially if the back of the head drops, the pressure is relieved. When fully stretched forward and down, the distance from the girth to the back of the head and to the mouth becomes shorter than when the head is raised. The device hangs.

Horses usually don’t even fight this device because its action is quite mild.

Additional equipment for working with champon on cord

Chambon puts pressure on the back of the head and mouth.

If you absolutely need to use something to stretch your horse, choose a chambon – it is cheaper and softer than the Pessoa system or the Abbott-Davies reins. The money you spend will not help your horse. Use the cheapest and gentlest system, and spend the money on massages for your horse and cord lessons.

Chambon takes the pressure off when the horse is stretching.

Put a chambon on the horse, and on the back, on both sides, attach an “elastic band” to the edge, adjusting it just above the hocks. I guarantee that the horse will feel the same pressure in the back as with the Pessoa system, but the chambon will allow him to stretch from front to front and down!

Remember that the horse can only stretch if it starts moving forward from the hindquarters, so train it slowly.

Pessoa system

The horse pulls his mouth, moving his own hind legs.

The Pessoa system is used for lunging. It is supposed to make the horse stretch and engage the hindquarters, encourage him to put his hind legs deeper under the body, so it’s good for the back. I have seen the system in action several times, and as long as it kept the horse head down, the most striking effect was that he was able to hit the horse with the snaffle in the mouth with every movement of the hind legs.

The system has knots that connect the back and front of the horse through the edge. My guess is that the rope that wraps around the horse from behind should encourage him to put his hind legs deeper under his body, while also limiting the height of his head. But which is more sensitive, the skin on the hind legs or the mouth!? The horse will lower his head down, but not stretch behind the snaffle, as the snaffle hits him with each step along the toothless edge and teeth …

I haven’t seen horses really engage their hindquarters in this “system” – they keep moving on the forehand and hiding behind the reins. The system can be adjusted to lower (for more stretch) and higher (for collection), but even so it will not be effective enough.

Hock Hobbles (system interacting with the hocks)

When moving, the horse receives blows to the mouth.

Some of these devices are so ignorant of the fact that the horse has a sensitive mouth that I am horrified. What else can be achieved by using a device that connects the mouth to the hocks?

Abbott-Davies balancing rein

The Abbott-Davies balancing rein connects the snaffle to the horse’s tail. In fact, this is a dead martingale, attached to the tail, stretched between the buttocks of the horse. Perhaps someone thinks that a horse will let his hindquarters down if he is pulled by the tail in this way? To bring the hindquarters in and step deeper under the body with the hind legs, the horse must move! In this case, the greatest impact will again be on the mouth. Don’t forget about the weight of the straps. In addition, this adaptation does not allow the horse to stretch his neck forward and down, prompting him only to stick his nose between his front legs.

“Cowboy dressage” dead martingale

Eitan Beth Halachmy called his riding “Cowboy Dressage”. “Discipline and dressage” he was taught by an officer of the Hungarian cavalry. Subsequently, Eitan became fascinated with the riding style of American cowboys and decided to combine the knowledge of both systems. The device he created involves connecting the snaffle to the horse’s tail so that the rope runs along the side of the horse. This should make the horse bend over and help get him into obedience…

Martingales and dead maringals

There are several types of martingales that limit the height to which the horse raises his head. The simplest ones are attached to a snaffle and a girth or strap around the shoulders. Some are attached to the snaffle rings or to the nose strap of the primer, some are attached to the reins with rings.

Sliding (hunting) martingale often used by competitors. It is really very useful on jumps, especially with horses that tend to slip the reins when approaching the barrier.

Hot or stubborn horses tend to throw their heads up sharply, and this is not like being in front of the reins in dressage. It looks like “nose to the sky and away we go.” The advantage of the sliding martingale is that it is designed in such a way that it starts working only when it is needed. When the rein rises above a certain level (the horse lifts its head), the rings hold it and bring the horse’s head back down. The rein is pushing down, not back. When the horse carries his head in a more acceptable position, the martinagal straps hang loosely. The martingale also serves to prevent the rein from slipping down and prevents the horse from stepping into it if the rider suddenly disappears from his back.

Irish martingale performs the same functions regarding rein support. You pass the reins through the rings, and the belt lies around the horse’s neck. If the horse raises its head, the strap rests on the neck and resists. When a horse behaves well, he doesn’t work.

The problem with martingales, however, is that most of them are not long enough or too open to allow fine rein work. This is convenient on jumps, but disastrous in dressage. The Irish martingale allows almost no sideways movement of the reins and can sometimes hold the reins closer than necessary in a neutral position. Therefore, martingales are not suitable for basic arena work.

Many variations of dead martingales are known. These are belts of a certain length, going from the head to the chest. One of them – harbridge.

It attaches to the primer nose strap like any dead martingale. It’s not that bad, but it’s not elastic, so when it starts to function, it can work extremely sharply, with a jerk.

For some horses with a tendency to shine, the use of such martingales can be life threatening. The martingale gives the horse enough room to lift his neck, and with a sharp jerk, the horse can get scared, stand on the candle and roll over.

With the help of an additional adapter, a dead martingale can be attached to the snaffle rings. So it becomes many times stricter and tougher. In addition, with such fastening, the snaffle rings are pulled down and come together, which creates the effect of pincers: the bit additionally breaks at the articulation point and rests against the sky. This can cause the horse to flash or run.

Alliance Back Lift (Complex system for lifting the back)

I haven’t tested this device yet, but it seems to work correctly by acting on the front, trying to raise the base of the neck. The system is not connected to the mouth and does not seem to cause the horse to twist its neck and go beyond the vertical. This device MAY be used to force the horse to lower its head, but does not “ask” it to stretch.

Teresa Sandin (source); translation by Valeria Smirnova.