10 meter circles: the geometric challenge of dressage

10 meter circles: the geometric challenge of dressage

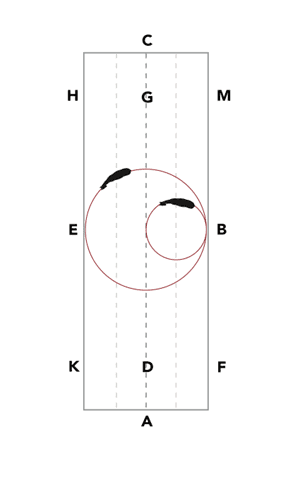

Circles are a kind of geometric challenge that dressage presents us with. A 10-meter volt is usually performed from the long wall to the center line. A geometrically correct volt should not get larger or smaller as you pass it. The circle has no straight lines or angles. In order to move around the circle correctly and balanced, the rider must sit correctly in the saddle, maintaining the proper bend of the horse in the direction of travel.

Developing circling skills will positively influence the rider’s ability to move around corners and prepare them to work on lateral movements.

The horse shows the correct bend on the 10m circle. It is evenly bent from the back of the head to the tail through the entire spine.

Rider seat

The seat of the rider has a direct impact on how well the horse can perform the 10 meter circle. The most important message for starting the movement along the volt is the position of the body of the rider. The rider must direct the horse into the turn first of all with the body, indicating to them the direction of movement. This will allow him to continue to use the reins and leg to ask the horse for direction and bend, and to control his balance. If the rider uses the inside rein to turn the horse, thus it can cause the horse to wallow in a turn or circle, losing proper bend and balance. The use of the reins as a means of control in the turn should be secondary to the body position of the rider. The rein should only be used when the horse is not listening to the rider’s signals.

To achieve the correct position in the saddle, the rider must have some understanding of their own biomechanics. It will be especially useful in this regard to work out with a trainer who will not only help you correct your landing, but also provide the necessary explanations.

Ideally, when riding in circles or circles, you should shift your balance slightly towards your inside thigh, keeping your shoulders in the direction of the turn, keeping your hands above the withers of the horse, pointing in the direction of travel. The outer leg should be slightly behind the girth, the inner leg at the girth. This position of the rider will give the horse the best chance of maintaining the correct balance on the circle. It also allows the rider to use the controls to fix the correct curve of her body.

Shifting the balance to the inside thigh should not be carried out in an exaggerated manner (for example, to the point where the rider begins to feel like he is falling or sliding to the appropriate side). Rather, you should have a sensation similar to that of standing on the ground with both feet and lifting one foot off the ground without leaning in the opposite direction. A person standing on the same ground will be able to properly balance himself, only without falling with his shoulders inward. This is an important feeling to be aware of, because in order for the rider to be truly balanced in the saddle, his body must be upright, and his chest must not roll forward or backward. Maintaining proper hip position helps keep the inner leg at the girth, which will create the right bend in the horse’s chest.

If the rider’s shoulders do not point in the direction of travel, or if they are too turned inward, this can cause problems. Your shoulders should be parallel to the horse’s shoulders. This is especially important when you start doing side work. If the rider cannot bring his shoulders into line of motion, he shifts his weight in the opposite direction, making it difficult for the horse to work properly. You can help yourself achieve the right feeling by visualizing walking up a spiral staircase. To climb it, a person must rotate their shoulders and align them with the center line of the stairs. This allows you to move to the next step without losing your balance and without shifting from the center. If a person deviates from the line of motion, he may fall.

Successful bend – a bend that coincides with the trajectory of movement and evenly passes through the spine of the horse from the back of the head to the tail.

Horse balance

If the position of the rider in the saddle is conducive to guiding the horse in the turn or in the circle, the rest of his controls can help to improve his balance. The natural tendency of a horse to turn is to fall into the turn, pushing his head and neck outward while his chest remains tight. This causes the horse to move forward. Therefore, the rider must ask the horse to bend in the direction of the path of the circle. Proper alignment and proper rider posture will allow the rider to use the controls effectively.

If you want to get an idea of what a proper curve should look like, imagine looking down on a horse. You should see a clear arc from the back of the head to the tail. If the horse turns his head and neck inward too much, he will lose the alignment of the outside shoulder and fall out of the circle. If the rider holds the arms in the direction of travel and above the withers. He can keep the horse from falling out with his outside rein and leg. The inside rein is free to support the rein while the inside leg holds the inside shoulder and flexes the horse at the chest.

If a horse tends to drop outward at the hip, he will tense his chest and lean inward. The rider’s outside leg should be positioned slightly behind the girth to prevent this. This will also encourage flexion of the horse’s chest around the inside leg. The inner leg at the girth keeps the chest curved and does not allow it to become enslaved and fall inward.

Exercise: turn on before

This exercise aims to improve the feeling of connection between the inside leg and the outside rein. It is important to enable the rider to slow down the forehand and connect with the hindquarters. This connection also gives the feeling of the horse’s chest giving way to the inside leg, which creates contact with the outside rein. Once the rider feels a good connection from the inside leg to the outside rein, he can stop the horse from falling in at the chest and out on the 10 meter circle.

1. Start from a stop, parallel to the wall of the arena.

2. Bend the horse at the poll towards the wall, making the former outside rein inward (“outside” is the opposite side of the rein).

3. Without losing contact on the new outside rein, ask the horse to move his hindquarters away from the wall. The back foot closest to the wall should step in front of the opposite back foot.

4. Continue to ask the horse to yield to the leg until he has half pirouetted and is in the opposite direction under the wall.

Correction of problems. A common mistake in this exercise is for the horse to walk forward instead of stepping to the side with its hind legs. To prevent this from happening, half-halt with the outside rein. If the horse is still going forward, ask him to stop before asking him to step sideways with his back.

In this exercise, bending the head and neck to the side should be avoided. If this problem occurs, the horse will fall out with the outside shoulder out. The outside rein should line the horse’s neck, while the outside leg can give a gentle momentum to keep the horse from bogging down. The rider must also engage the body, signaling the horse not to move forward or sideways.

Another common mistake is to sit “outside”. The rider needs to balance in the direction of the bend so that the external controls keep the horse from sideways.

This exercise gives the rider an understanding of how to keep the horse in the controls when they are coordinated and connected. Mastering this range of controls is essential to successfully executing 10 meter circles because it allows the rider to maintain a proper balanced bend.

Corine Foxley (source); translation Valeria Smirnova.